Is VIA HFR the Canadian Brightline?

A look into Canada's first attempt at a modern, intercity passenger rail network

*Authors Note: Since this article was originally written there have been numerous developments and changes to the HFR project making some sections of this piece outdated. Since a lot of the article focuses on the geographic, and social context of the where the proposed line would run most of it is still relevant, but in the future an updated version will be published in order to reflect recent developments.*

There shouldn’t really be anything too complicated, or even that interesting, about the VIA High Frequency Rail (HFR) project. After all its just a train, how difficult or controversial could that be? But as it turns out, there is a lot going on with this project, and a lot to investigate, unravel, and unpack. Some of it is rather clever and exciting, while other parts are simply abysmal. Compounding it all is the fact that the project remains in a hazy state, with new announcements eliciting more questions rather than clarifying what is going on.

The article really centres around a tour of the line, following it for its entire length, pulling back the layers, and revealing the complexity of the project. Like an Icelandic landscape, the line never really stays the same for very long. Each section illustrates a different part of the HFR project, along with all the communities along the way and the associated opportunities and challenges. Canadian storytelling is often rooted in journeys across the land and while this article lacks the poetic beauty of a Tragically Hip song, the spirit of it is there.

In theory, HFR could be a transformative project. It could radically change how people move between cities and towns from Toronto to Quebec (and eventually the full length of the Quebec-Windsor corridor). The entirety of the corridor is home to 61% of the Canadian population and while not everyone will stand to benefit from it, a large minority of Canadians could. In many ways it is remarkably thoughtful and pragmatic… the ideal project for a largely suburban, but urbanizing, country that is looking to take its first kick at the can at building properly modern intercity rail.

But HFR is not without its faults. There are quality of life concerns for those who will suddenly find a busy line running through their town, farmland, or backyard. It could serve as a way to do some union busting, sell off federal land to developers with deep pockets instead of using it to address the housing crisis, and further fuel the resentment many people have towards those with anti-rural attitudes. And most damning of all, it could turn out to be a project for “the best of us”, not “the rest of us”.

Boring origins for a bureaucratic endeavour

The simplest way to describe the HFR project is that it’s going to be like VIA Rail today, but with modern trains, more frequent service, faster travel times, lines free of freight traffic, and…. it will actually be reliable. Yes, there are many more details about the project beyond that, but for the public, that is what they are going to see (though modern trains are something that will be arriving much sooner than that). Some parts of the first phase of the project will be on lines that currently have VIA service, while other sections will be all new. That will result in several cities that currently do not have VIA service, or any train service for that matter, being connected into the VIA network.

A new VIA Rail train is out on test and stopped at Napanee station. The trains themselves can do 200km/h in their current state and are quite comfy and modern inside. This is also essentially what HFR will look like, except with overhead wires for electric trains, and tracks that are free of freight trains.

Since the 1980’s, there has almost always been a push, from one group or another, to build high speed rail in Canada, primarily modelled after France’s TGV or the Shinkansen in Japan. Prior to the HFR concept becoming public, the most recent high speed rail report had been in 2011, which put the costs of a high speed line from Windsor to Quebec at CAD21.3 billion, and like most HSR proposals in the past, dropped service to many towns and cities along the existing routes. Not surprisingly, it went no where and became another dusty collection of papers on a shelf.

This is a map of the most recent Quebec-Windsor high speed rail proposal (though an Ontario centric one from Toronto to London was released several years after this one). It has all the hallmarks of previous proposals, in that it had no concern for places in between the major cities, or even the suburban stations (Fallowfield is gone, and there is just one station for the east end of Toronto and the eastern GTA). Image via CatBus.

In 2015, a different kind of proposal emerged, if if the map looked rather familiar. This one was not from consultants or a consortium of rail manufacturers looking to drum up federal investment so that it could make some sales. It came from VIA Rail itself and it would be a CAD4 billion project. One of its key selling point was that it would use existing, and abandoned, Canadian Pacific corridors, in addition to some of the limited track it owned itself, to create a moderately faster and more frequent service.

One of the earliest maps showing the HFR proposal. Several stations on the early maps would disappear from later iterations. Image by VIA from Railway Age.

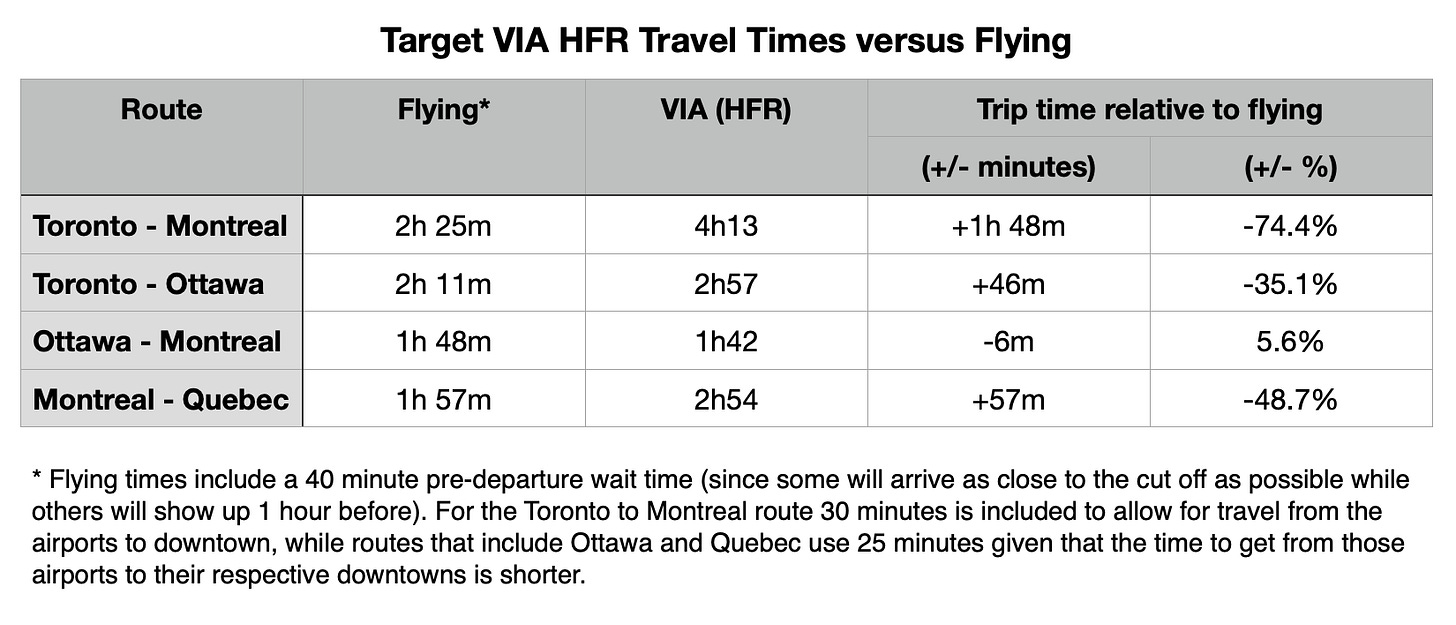

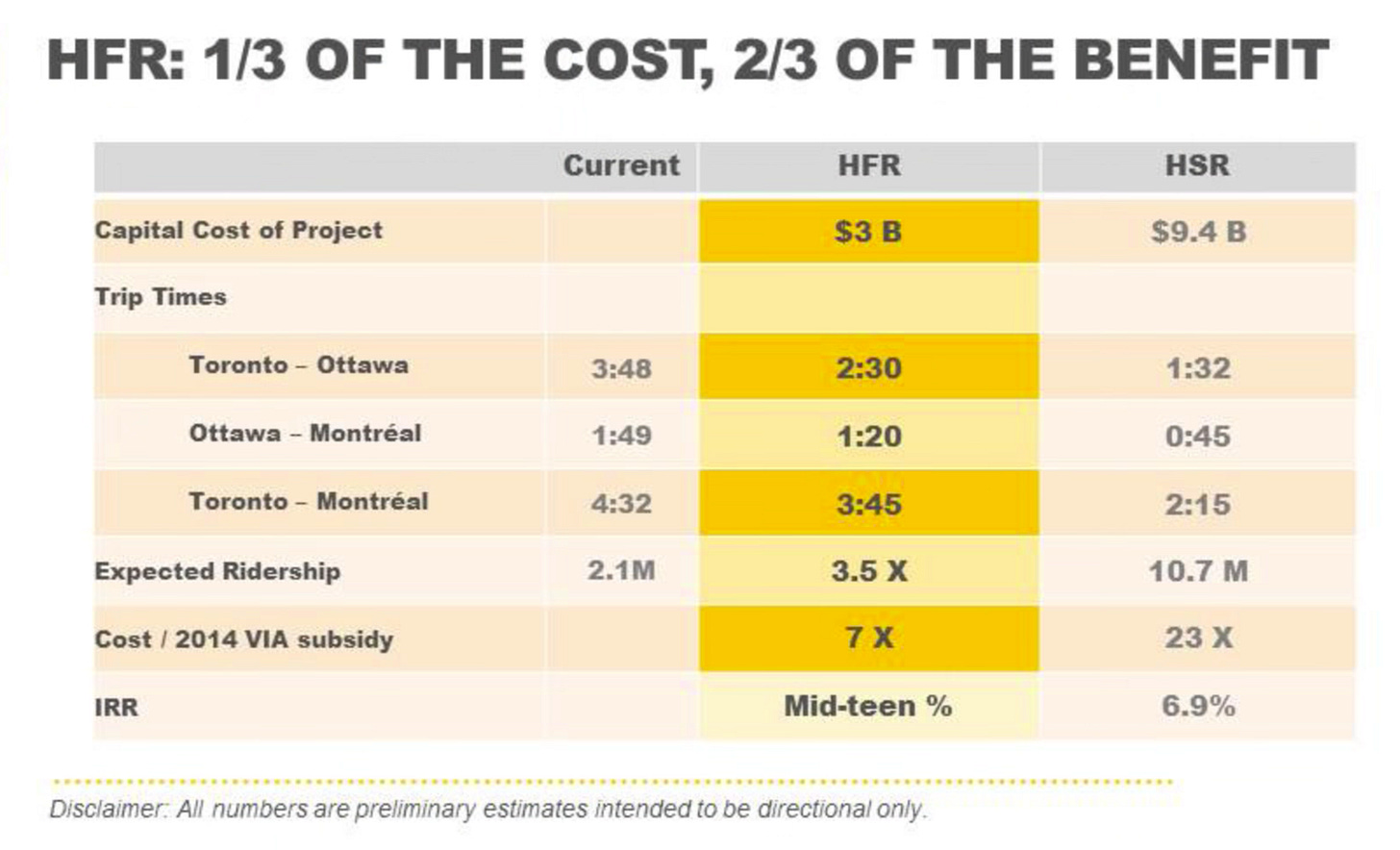

At first glance, it was kind of boring. It wasn’t the “spend just enough so that a failing system doesn’t completely breakdown” approach towards passenger rail funding that had been the mantra since VIA’s inception. But it avoided being a “lets go from zero to a thousand and spend at least CAD20 billion on a high speed rail” report that would ultimately be mocked, or simply ignored. It fell somewhere in the middle. The project was developed by VIA Rail bureaucrats and would offer improved, modernized, service without a scary price tag. In the early life of the project there was even a tag line “HFR: 1/3 of the cost, 2/3 of the benefit" which, god bless their best intentions, is the most Ottawa committee brained slogan they could have come up with.

It was also naively optimistic in its cost projection. Then VIA Rail CEO Yves Desjardins-Siciliano put the price tag at CAD4 billion. When broken down this equated to CAD2 billion for infrastructure, CAD1 billion for trains and stations, and the remaining CAD1 billion for electrification. For the most part, this is the number (or CAD4.4 billion) that only until very recently, was most often quoted by the media or government officials. The reasons why this number was never realistic will become clear as the article progresses.

Early reaction to the idea was mixed, though it wasn’t overly terrible. There was a lot of cynicism about yet another proposal that was going to go nowhere. But, among the local communities it was going to serve, especially places like Peterborough, there was genuine excitement.

For the next few years the project was not really in the public spotlight. There were of course newspaper articles about it from time to time and from an outside perspective it may have looked dormant or dead. But work was going on behind the scenes. The 2016 federal budget allocated CAD3.3 million to Transport Canada to investigate the viability of the project, and the 2018 federal budget added another CAD8 million for the work to carry on and the scope to be expanded.

It would be in June 2019 that it became apparent the project was starting to be taken seriously. A total of CAD71.1 million in funding was being dedicated to further the project. CAD55 million of that amount was for the Canadian Infrastructure Bank to create a joint project office that would work with the third party groups needed to conduct detailed studies. And CAD16.1 million went to Transport Canada with the focus being on interoperability of the new service with transit agencies in Montreal and Toronto, those being EXO and GO.

It was also in the later half of 2019 that VIA themselves began to promote the HFR project, something they had never done in the past. They released a video on their YouTube channel outlining the proposal, included information on their website, and even put up posters in their train stations. As was discussed in detail in a previous article about the evolution of VIA’s brand and marketing, this was tied into a much larger modernization and rebranding campaign.

On 19 April 2021, a little under two years after the funding for the now joint CIB and VIA Rail project was allocated, the 2021 federal budget was announced and it was very good for HFR. CAD4.4 million would go to Transport Canada for risk assessment and mitigation, and CAD491.2 million for VIA Rail over 6 years. That money would not only be used to further the project through the procurement phase, but also undertake some early infrastructure work (though the details of what kind of work that might be are not yet known).

On 6 July 2021 Minister of Transport Omar Alghabra went on a mini tour, starting in Quebec City, to announce that HFR was going to be moving on to the procurement phase. A few weeks later, on 21 July 2022, the minister took a small tour of Southwest Ontario to announce that they would start investigations into Phase 2 of HFR which would see it serve London, Windsor, Sarnia, and presumably at least a few points in between. Originally set to launch in Fall of 2021, the procurement site, and process, for HFR officially began on 9 March 2022, which is where the project currently stands as of today.

These might be somewhat boring details, but they are important. The cultural and political viability of this project, something that will be discussed later, is a central factor in its progress to date. The rather bureaucratic process it has undergone thus far is illustrative of that fact.

But that isn’t what most people will care about. Where does, and doesn’t, the train go? What will be built in order to get the project done? What will the impacts on people nearby be? And most importantly is it something that will be useful? Those are the kinds of details that will be relevant. And there is no is better way to get a sense of what the project is really all about then to go on an 850 km long tour of the line.

The changing nature of Canadian cities

Toronto has in many ways, and for a long time, been at the vanguard for how cities across the country have developed. Kicking off in the 50’s and 60’s, and really carrying on at full steam until well into the 00’s, Toronto and the GTA were the poster child of suburban living. Being so heavily tied to the automobile this off course had massive implications for how people moved not just within their city, but to cities near and far. While there were many factors at play, including the rise of affordable airline travel, intercity passenger rail was never on the agenda in a serious way once people had decided that public money was better suited for highways and airports, but not trains.

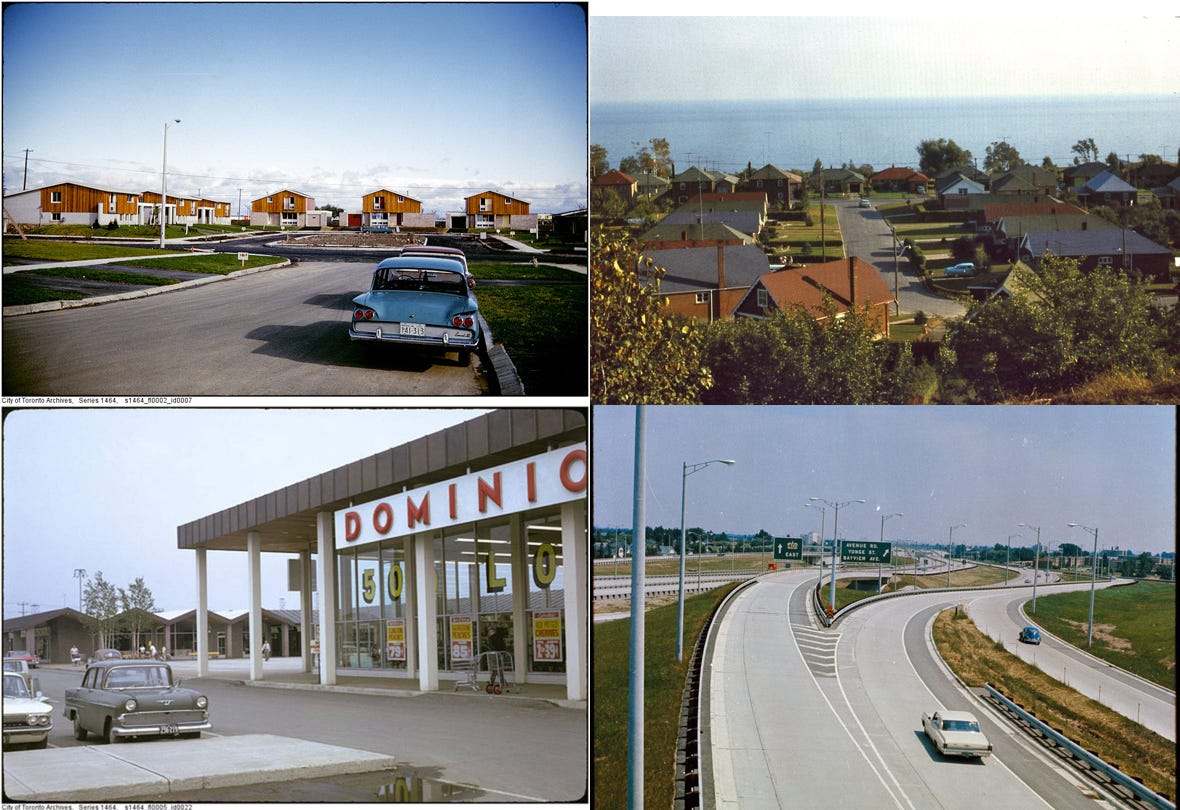

This is Toronto in the 1960’s. Suburban living and plenty of highways is what people wanted, and that is what they got. This model served as a template for many other cities in the corridor and across Canada and there was very little deviation from this up until the late 1990’s. Trains were largely irrelevant, and not really viable, in landscapes like these. Images from City of Toronto Archives via BlogTO.

Throughout the 80’s and 90’s, while the great suburbaning was in its final years of a triumphal run, people were slowly moving back to Toronto’s urban core. At first it was primarily filling up existing housing, but in the late 90’s and early 00’s it would evolve into constructing all new urban homes, primarily in the form of townhomes, warehouse conversions, and increasingly condo towers. Eventually it would spread outside of the urban core and into the suburbs on the lands of dead malls and parking lots.

The rest as they say is history and before long a full scale urban revival was taking place in Toronto, along with many other cities in the Quebec-Windsor corridor and across Canada. With urban living comes a need for urban transport. After all, part of the appeal and joy of living in a city is not needing a car for most, if not all, the trips you do. And that has sparked a willingness to invest in public transport in a serious way, though the focus is still primarily on more local needs rather than regional and longer distances, at the moment.

At Union Station, change is already afoot. GO has embarked on a massive modernization campaign that is going to turn it into one of the busiest train stations in all of North America. And not surprisingly this is where the HFR line will start as well. Toronto as a destination is going to be a key factor in the success of intercity rail in the future. Not only is it the largest city in Canada, but it has many people who are car-free or car-light. If you don’t have a car, or your partner needs the one household vehicle, you have no choice but to find other options for intercity travel. In 2019, the percentage of VIA Rail trips that involved Toronto as either a departure point, or arrival destination, was 62.2%. It might also be surprising that the busiest city-pairing for Toronto was not Montreal, but Ottawa, in large part owing to a higher frequency of service between the two cities.

It shouldn’t come as a surprise that the largest cities are the top destinations and sources of traffic for Toronto. But even substantially smaller centres such as Kingston, London, Windsor and Cobourg, provide a respectable amount of traffic. Data from VIA Rail Canada.

Unlike the current VIA Rail service, HFR is going to take an entirely different line, one that runs north of the Lakeshore corridor and the 407. Right away a big question emerges, how do you get trains from Union Station to the northern edge of Toronto so that it can head out of the GTA?

There are a few ways this can be done. The first, and probably most likely option, is to take the GO Lakeshore East line, then head north on the GO Stouffeville line before cutting onto the Canadian Pacific corridor. HFR could also take the GO Richmond Hill line for roughly half the trip, then the Canadian Pacific corridor for the other half. While super scenic, this is probably not great as the line is incredibly curvy as it goes through the Don Valley and wouldn’t do a good job of quickly getting trains out of the city. There is also a third option, that uses a long abandoned freight corridor, and then building in the existing Canadian Pacific corridor. That is probably the most ideal as it would essentially give HFR its own corridor in and out of the city. But it is also the most expensive.

The map shows 3 options for getting trains from Union Station to Agincourt, and beyond. What kind of agreements or partnerships can be negotiated with Metrolinx will likely have just as much of an impact on route selection as factors like cost and travel time. For being so close to the GTA, there is not a huge amount of urban development between Markham and Peterborough (in part because of the greenbelt). Most of the land is used for farming, with the odd gold course or forest tossed in just to mix things up.

Publicly, there has been no firm indication as to what direction this section might take. In theory the Stouffeville line would be the best option since it will soon be electrified and modernized, and require the least amount of infrastructure work. But with Metrolinx having some very aggressive plans to run services up to every 6 minutes on some of its GO lines capacity could be an issue. This section of the HFR line is very much a wait and see situation.

It is important to recognize how critical urban parts of the HFR network will be. Whether it is a highway or a rail corridor, both can become extremely busy, congested, and slow through the most central part of urban areas. Because of quality of life concerns for residents nearby, trains are unlikely to go much beyond 140km/h, which will be the top speed of GO trains on their modernized network. But if a train has to limp along at 50 or 60km/h, due to traffic or other factors, that is going to add a significant amount of time to a trip, depending on how long the train has to do that for. In a July 2021 announcement about HFR, it was stated that they were looking to accelerate “dialogue with partner railways to negotiate dedicated routes in and out of city centres”, so those in charge of the project seem to be aware of the value of dealing with these sections correctly. But there is also a much higher cost for building in urban areas, so it will have to be a fine balance between speed, capacity, and cost.

What are the ingredients for a modern railway?

Not all the rail lines are the same and at a quick glance it might not seem obvious what the difference is between a line that can only suit freight trains moving at 40km/h, and one that allows trains to travel along at 177km/h, or faster. Once the HFR line gets past the Canadian Pacific rail yard in Agincourt and starts heading to Peterborough, it is quite easy to illustrate a number of factors at play when it comes to the design of a rail line.

In general there are about half a dozen key factors that need to be considered when determining the quality rail line that can be built, and how fast a train can go: geometry, track quality, number of level crossings, topography and geology, signalling, and whether it operates in mixed traffic. Some of them seem straight forward enough. A straight line is going to allow trains to go faster than a twisty, curvy line. Building a line through the prairies is going to be easier, and cheaper, then building a line throughs the Rockies, even if you do follow the contours of landscape, let alone try to build straight through it.

Some are perhaps a little less intuitive. The current line from Agincourt to Peterborough has track which is in pretty rough shape. From a distance you wouldn’t really notice it, but up close you can see that the sleepers (the wood that tracks rest on, and are secured too), are heavily rotted in many locations, and the rails are bolted together instead of welded (which is what creates the classic ‘clickity clack’ sound). There is also the signalling system, which is fine for slow moving freight trains, but not really suitable for fast moving passenger trains.

And then there are all the crossings, the parts of the line where roads, bike/pedestrian paths, driveways, or farm crossings, go directly over the track.

Various shots of the existing Canadian Pacific line just west of Peterborough and at the cities urban fringes. At a distance, it just seems like any other rail line. But up close it is clear the line is completely unusable for passenger rail service in its current state.

How well crossings are protected are a huge determining factor in how fast trains are able to operate on a rail line. If a line has crossings that are only marked by cross hatches and stop signs (so no lights, no bells, no gates), then its speed is effectively restricted to 41 km/h or 49 km/h (depending on if it is a freight or passenger train though some lines are, at the moment, able to operate faster). In the past farm crossings were exempt from this though that has changed in recent years. Both private and farm type crossings will be covered in more detail later as they provide their own unique challenges.

If a line has a continuous string of crossings which are protected by automated signalling, so lights, bells, and gates, then speeds up to 177km/h can be achieved if all other aspects of the track, and the trains being used, allow for it. For anything above that, crossings must be completely grade separated, meaning vehicle, pedestrian or bike traffic goes under or over it.

On a line with a dozen, slow moving, freight trains each week, grade separated crossings are really only necessary for freeways, super busy provincial roads, or other busy rail lines. But the faster trains go, and the more traffic the line sees, the more they become a necessity, least in part to increase safety, but also so that constantly stopping traffic in its tracks as they wait for trains to pass can be avoided. Along the HFR line, there are a lot of crossings. How many exactly? 891, and that does not include the sections of the line that run through the urban parts of Toronto, Montreal or Laval.

Of those crossings 71 are already grade separated, so there is a chance most of those won’t be a concern (though some might be narrow enough that they have to be modified or replaced, depending on the situation). There are 367 regular, level road crossings, many of which are rural roads with just signs, or lights but no gates. And then there are the 426 farm crossings, and 27 private crossings.

A breakdown of the different crossing types through the various sections of the HFR line (excluding the urban areas of Toronto and Montreal). This does not include the crossing on a potential bypass from Smiths Falls to De Beaujeu. Once crossings from that section, and the urban areas included, the number of crossings tops the 1100 mark. Data from Statistics Canada and Google Earth.

Needless to say that is an extraordinary amount of crossings that either need to be deleted, upgraded to modernized automated signalling, or fully separated if higher operating speeds are desired. The cost of adding automated signalling systems is not excessive. A 2017 report by the city of Abottsford put the cost at around CAD275,000 per crossing. In some cases it might be a bit higher if power lines have to be run to the site, but that number seems a reasonable estimate. Grade separated crossings however, are much more expensive, by a factor of at least 100.

For example an underpass on Adelaide St in London, Ontario cost CAD58 million. A program to do 5 grade separations in the City of Ottawa would be CAD430 million. In the Barrhaven, a satellite suburb of Ottawa, a rail underpass on Greenbank Rd was CAD43 million. An underpass to separate Main St and the Canadian Pacific line through Milton, ON cost CAD49 million, in 2015. These were all within cities, mostly 4 lane roads (or more), underpasses, and require extensive work to deal with sewers and utilities. But even a simple two lane provincial highway, or even rural road, overpass is going to be in the CAD25 - 30 million range, at a minimum. It is easy to see how quickly the cost of grade separation can add up.

Through Peterborough there are going to be some challenges with the number of roads the line crosses. There are a dozen level crossings from where the line enters the city limits to the river, and only a single grade separated one at the cities periphery. To ensure quality of life for residents once the number of trains increases, this will mean a handful of those at a minimum will need to be separated so that people can still have a consistent flow throughout the city.

Looking west to where the current Canadian Pacific line, and future HFR line crosses George St, a critical artery for heading into Peterborough’s downtown. Right now having a level crossing is no big deal when its one or two freight trains a day. But 30-40 passenger trains in a day will be a very different story. Also visible, to the right of the track, is the old train station.

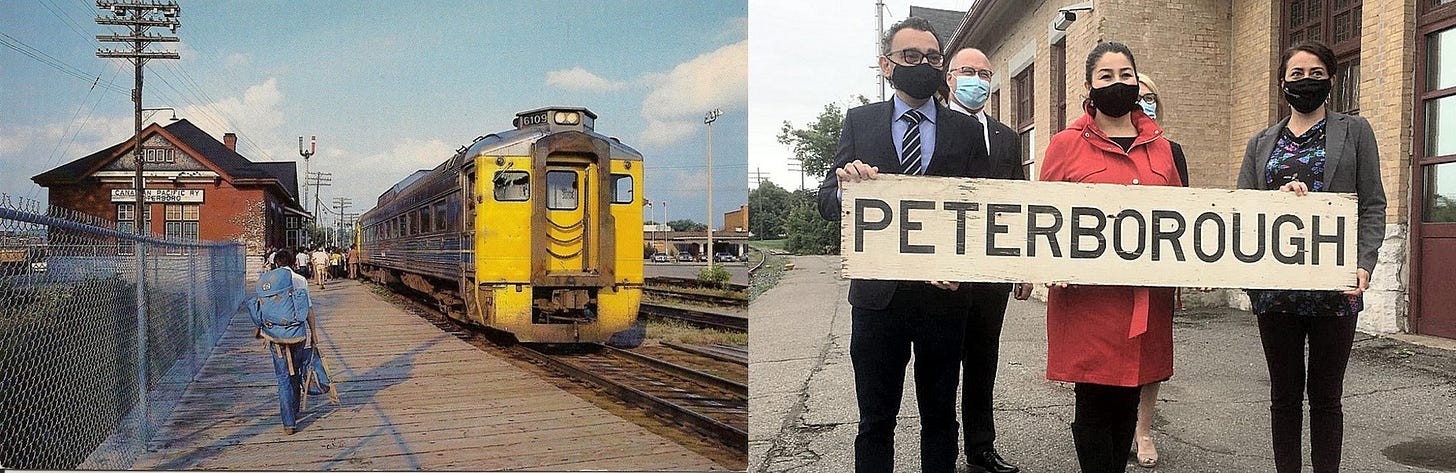

Peterborough did at one point, up until January 1990, have VIA Rail service. Like many VIA lines in the 1980’s, it struggled as passenger counts dwindled. Even with the line using RDC Budd Cars, a self propelled diesel passenger car that could operate as just a single unit to try to save money on lines that were bleeding cash, it eventually met the axe. Unsurprisingly, due to the cities decades long lobbying and advocacy efforts, and cheerleading for the the project, when major HFR announcements have been made, the city is often one of the locations they head too.

On the left is an undated image of a VIA RDC train stopped at a then painted Peterborough station, probably towards the end of the lines life. On the right is Transport Minister Omar Alghabra and local representatives having a photo op outside the station. Left image from Peterborough Chamber of Commerce via PTBO Canada. Right image from Global News.

Community advocacy and engagement have played a sizeable role in building public support for this project. Trois-Rivieres was another city that was active in pushing for the return of rail service, which it also lost that first month of 1990. Other communities along the line, which have currently been left of the maps, such as Perth and Sharbot Lake are finding their voice and communicating not just their desire for a station, but the ways they hope the line can be designed to reduce the impacts of dozens of high speed trains whizzing through their towns each day. These voices, both positive and negative in tone, are only set to increase as the project moves along.

A big consideration for the line into Peterborough (and a bit further east to Havelock), is going to be the existing freight traffic. This section is not part of Canadian Pacific’s mainline between Toronto and Montreal so the amount of traffic is relatively light. But there are still customers on the line. It serves Masterfeeds west of Peterborough, Quaker which still has its plant right in the heart of the city, a few quarries owned by Unimin Canada that are connected via a track that heads north from Havelock, and a rail yard in Havelock itself.

The Quaker facility in Peterborough. As with many agricultural industries, rail is essential as it is the only cost effective way to move the product long distances, in this case oats coming from western Canada or an eastern Canada port. Even though the line doesn’t serve that many customers, for those that need it is the difference between staying afloat, and shutting their doors.

Because freight traffic is not particularly heavy on this line, it does mean that VIA could negotiate a deal in which they assume full control of the corridor, and offer running rights to Canadian Pacific when the line isn’t in use so they can continue freight service to their customers. This would be ideal as it means there would less work required on the corridor itself. Using the existing line will result in some cost savings, but not as much as one might intuitively think it would. As was seen in the photos above in its current state the rail line is completely unsuitable for passenger service. Level crossings would all have to be updated, except for the few that might need full grade separation. There would also need to be signal upgrades, preparing the right of way for electrification, and vegetation clearance, so there is still a reasonable amount of work that would be needed to modernize the line.

Just put a track on it

By and large the section from Peterborough to Havelock is not much different from the previous one. The track is in poor shape, and even the landscape is pretty much the same. Perhaps the only major difference is that many of the level crossings are on rural, gravel roads, as opposed to paved ones, meaning a potentially higher cost to install automated signalling at them.

A rural road west of Norwood. These are a staple along many parts of the HFR route and most are simply protected by a cross hatch and stop sign.

The line does pass through the small community of Indian River, and the charming little town of Norwood. But aside from that it primarily runs through farm land. Interestingly there are very few farm crossings on this section, perhaps owing to the frequency of local roads.

From Peterborough to Tweed the landscape does start to shift a bit. The line isn’t particularly straight, but it is not excessively twisty. There are some communities along the way and the majority of the line still runs through farmland.

As the line heads east from Havelock it officially enters a state of abandonment, and it remains this way until reaching Glen Tay, 130 km down the line.. Many moons ago there was an active rail line the full length of this section. But at this point it has been abandoned for at least 30 years. Immediately east of Havelock there are even some sections of the corridor with track still in it, but they are overgrown and in some cases even have roads simply paved over top of them.

Looking west on a section of the now abandoned Canadian Pacific corridor east of Havelock. It isn’t just cities that pave over old streetcar or freight line tracks. Luckily there are not many sections like this along the HFR route as it will take some work to rip out the track and ties, old signals, cut back brush, redo the drainage, and get it into a good state.

From the start the use of existing corridors was a selling point for the HFR project. This often times questionable marketing ploy is not entirely new though. It is essentially an iteration of a type of public transport proposal that can best be summed up as “put a train on it”. If you see a rail line, and it has no passenger trains on it (bonus points if it had passenger trains on it in the past), then you know, just put a train on it. Its a rail line after all, so clearly that strategy just makes sense.

Part of the reason it became popular is because it has worked recently… once… kind of. The first GO train line was a sort of precursor to this, but the modern version emerged when Ottawa launched the Carelton University shuttle (also known as the O-Train pilot project) in 2001. They took a minimally used freight line, added some basic stations, and “put a train on it”.

If one of the main selling points of a public transport project is that “it’ll be easy because we can just put a train on it and let’r go” it is probably not a well thought out idea, and is likely going to cost way more than originally marketed as. Image from Portlandia.

If you were going to Carelton University then this line proved useful and a much nicer experience then taking one of the buses to get there. But that was really the extent of the lines function and though being a Carelton U shuttle isn’t a bad thing, it would ultimately take numerous, much more expensive, investments down the line to create something that was useful beyond the lines original, limited scope (and even then the current round of upgrades still fall short). None of that has stopped people from adopting the “put a train on it” philosophy for other projects, whether it was extending the Carelton U shuttle line across the river into Gatineau, or putting passenger trains back on to Vancouver Island.

Those two examples are not just the most consistent in beating the drum of that strategy, but they also show why this idea is rather simplistic and flawed. Sure you could extend the line into Gatineau, but it skirts around the most central part of the city, the place that most people would actually want to go, really limiting how helpful it would be for everyday commuters and riders (great if you want to get to the casino though). And in the case of Vancouver Island, where the line does actually go to the places people would want to get to, there are major repairs, to the tune of CAD728 million that are needed to be done to the line before a further investment of CAD599 million could be made to actually establish a commuter service on it (the poor state of the line was part of the reason it was shuttered in the first place). But the “just put a train on it” slogan is great from a marketing perspective in that it seems to offer a cheap, simple solution to a complex problem, which is why it is so commonly used.

The early days of HFR were a twist on that concept, opting for a “put a track on it” strategy. Presumably part of the reason this route was chosen is because there were abandoned sections where the rail beds were still fully in place, whether they had rotting tracks, or a recreational path on top of them. In sections with active freight lines, there are sometimes empty rail beds owing to once double tracked lines now being a single track. Even VIA Rail themselves trumpeted this approach as part of its public pitch in a YouTube video released in 2019.

Looking west on the old Canadian Pacific corridor, just south of Arden. Sections like this are good because a lot of work is already done. But they are far from track ready. All the culverts and bridges will need to be replaced (or heavily refurbished). It will need all the supporting infrastructure, probably some widening near old timey rock cuts. These sections are no doubt cheaper than all new right of ways (if they are suitable for modern service), but not “we can do this for CAD4 billion” cheap.

If the line is useful (ie it actually goes to places where people are and want to travel to), then there is nothing inherently wrong with this approach. It can actually save money versus having to build an all new right of way, with land acquisition costs and constructing the corridor itself being hugely expensive. But in this case it has also lead to a simplification of the project, and an underestimate of its costs in the early days. The idea that a 850 km long modernized rail corridor could be built for CAD4 billion was, at best, rather naive.

A case in point is the town of Tweed. The right-of-way, which at this point hasn’t seen a train in decades, runs right through the town. As it stands today there is no grade separation between the corridor and local streets, one of which is a semi-busy provincial highway.

Even if there are places where you can simply “put a track on it” the costs associated with reducing the impacts on people living nearby can be significant. Not only would the HFR line run right through the centre of Tweed, it would even run through the middle of the yard of a busy pallet factory. It might be easy to dismiss that and just tell them to move elsewhere and deal with it. But for 3 decades the town has evolved to function without a railway running through it. Suddenly sending at least a dozen trains a day flying down the track is going to be a disruption. And from an operations perspective, sending trains flying at every possible opportunity is exactly what you want to do.

It is easy to make jokes about a pallet factory. But this is what has happened along the abandoned sections of the line. In this case the right of way that goes through Tweed now has a large yard on both sides of it to support the local pallet factory (they do have to be built somewhere). Life hasn’t stood still since trains stopped running 30 years ago, or more in some cases, and bringing rails and trains back to the corridor means finding ways to reintegrate back into the various communities along the way so that it is not completely disruptive.

There are mitigation efforts to reduce the impact on people living nearby and keep traffic flowing, but they will add a not insignificant cost versus just throwing some track down. The situation in Tweed isn’t unique either. Many of the towns along the line east of Laval, and in particular east of Trois-Rivieres, are nestled right up to the currently slow moving freight line. It is the difference between drawing lines on a map and actually recognizing there are people along the way. People who aren’t just a potential passenger count, but are doing what everyone does and just trying to live a cozy, comfy life.

After the line leaves Tweed the terrain quickly changes as it heads into classic Canadian Shield country. This is a landscape that is all about granite, trees, and lakes. When this line was originally constructed, the primary consideration for its routing would have been to avoid tunnels, bridges and blasting and only use them as an absolutely last resort. This means that the line had to follow ridges and valleys in order to keep costs and construction time down. Since the goal wasn’t to build a line that could handle trains speeding along at 150 or 200km/h it didn’t matter if some sections were curvy and circuitous. It was a worthwhile trade off.

This is a photo of Sheffield Conservation Area, just south of Kaladar. This is pretty much what the terrain looks like across the full length of the line from Tweed to just outside of Glen Tay. It is very pretty, but all the granite, lakes and rivers make straightening existing sections of the line an expensive proposition. Image by Peter Sherlock-Hubbard via Canada 247.

Fast forward to 2022 and the needs of the line are far different than what they were in the past. All things considered, the alignment is surprisingly suitable for many parts of the corridor through the rocky landscape. However, there are some sections where trains will no doubt have to slow down in order to navigate tighter curves, less than ideal when the goal is to build a reasonably fast service. One solution would be to simply build a new right-of-way through some of the sections to create a straighter alignment that would meet the standards the rest of the line is looking to achieve. But that will require blasting, bridges over lakes, rivers, or valleys, and maybe even some short tunnels. Even if it was only 12-15km of realignment that was needed to achieve the end goal of a modern right of way, it would require a good amount of money.

It is very easy to see how the contours of the landscape and the presence of many lakes and rivers dictated the route through this area. While realigning some of the right of way would be an easier task today than when the line was originally built, it would not be cheap to do through the granite landscape.

Though this land looks relatively remote, there is another consideration that it brings up, and that is the indigenous communities along the way. Official HFR documents actually put the total number of communities along the full length of the line at 30 and of course they say all the correct things about consulting with them throughout the process. The maps show far fewer than this but that is because they only show federally owned or recognized indigenous lands. In reality most of the land is still unceded and not officially recognized.

In the past, railways very often destroyed indigenous communities and ways of life as they were laid down. It is entirely possible this corridor was no different in that regard. This makes rail lines a particularly sensitive and challenging issue so that the same pattern isn’t repeated today. The subject of negotiations, how to respect the land and, hopefully, how to include the communities in some of the lines benefits is an incredibly complex one. Devoting just a few paragraphs to the topic isn’t because it is being dismissed. It is important and a future article will go deep into the topic as this is not the only project in which this issue matters.

The HFR line is lucky in that geology and topography are not are a key consideration throughout most of its length. The section through the classic shield landscape is only about 95km and once the line gets to Glen Tay (which is really just a few minutes west of Perth) the landscape levels out. From there it starts a near continuous run through relatively flat agricultural land, with the odd bit of scrub brush in between, until it reaches Montreal.

Though few have likely heard of Glen Tay it is as a key point along the route. This is where the abandoned corridor ends and there is once again a rail line with active freight traffic. Unlike the previous section from Agincourt to Havelock, this one is much more active as it is part of Canadian Pacific’s mainline between Toronto and Montreal. While the track is in good shape that doesn’t matter. The line is busy enough that VIA will need to build its own tracks in the corridor instead of taking over it and offering running rights. Luckily the right of way is wide enough that while some earthworks will be needed, it shouldn’t be overly complicated to add additional tracks for HFR.

Looking east down the Canadian Pacific freight line through Glen Tay. Numerous parts of this line once had additional track, and in this section that appears to be the case, making it a bit easier and cheaper for the HFR project.

From Glen Tay to western edge of Perth, it would probably only take a couple strategically placed grade separations to minimize the impacts of increased rail traffic through the town. The corridor is reasonably buffered from built up areas so a bit of thought and care will go a very long way in adapting the line to the growing community.

Scalability, HFR’s party piece

Once the line leaves Perth and heads to Smiths Falls, what is perhaps the most important and underrated aspect of HFR really comes into play, scalability. Simply put it is building infrastructure, be it roads, railways, or computer networks, with an eye towards the future so that they can easily have additional elements added plug and play style as needed. The proposed HFR line has numerous sections, plus a 100km section of a wild card bypass, which are nearly dead straight and would provide excellent opportunities for trains to open up the taps and take er’ out for a rip.

You can create a single track corridor, electrify, modernize signalling, and maybe make some slight adjustments on alignment, so that the corridor is good to go in the future. Need higher speeds? You can start to grade separate. Need more capacity? Add a second track. In particular when it comes to grade separations the cost or complexity, for the most part, really doesn’t change as the rest of the infrastructure evolves (underpasses are an exception because it will be cheaper and easier to create one when a corridor that does not have an active rail line, versus one that does). As long as the backbone of the system is in place from the start, you can go back and add separations to bump up line speeds with little or no financial penalty for doing it after the fact.

There is an immediate benefit as well and that is keeping the price tag of the project down. Its clear there was no way it could have been done for CAD4 billion, and the recent announcements of a cost in the range of CAD6 - 12 billion really didn’t ruffle too many feathers. But somewhere there is a cost ceiling for the project after which point the public is going to quickly turn against it. Avoiding that is going to be critical. While the project is potentially going to have a fair amount of private funding, it already has, and will continue to receive public money, and public resources like land. That means it will stay in the same line of fire that any other public transport project does.

Demonstrating that investments in modernized intercity rail are worthwhile is not going to be a one time thing. HFR, will have to prove over the course of a few decades, through the design, consultation and construction phase and into the first decade of operation, that intercity rail modernization is a good use of public money. Having a network design that can be upgraded to respond to demand quickly and easily will be a part of that process.

From Perth to Smiths Falls the line is essentially straight and marks the first part of the route where a grade separated network, alongside the proper supporting infrastructure, could easily support speeds of 200km/h or more. Smiths Falls itself is a bit of a mess. Without going too far into the weeds, the existing station will almost certainly need to be moved, and a short 3 km bypass constructed, so that trains passing by don’t have to slow down, and to avoid what would currently be a very wonky situation of trains driving in and backing out, whether they were stopping there or not.

From Perth to Ottawa and onward to Casselman, straightness is the name of the game. The only parts of the line with any major curves are in Ottawa, where trains will have to slow down regardless, and Smiths Falls, though that can be sorted out. Equally important will be the growth of the communities on the eastern and western approach to the city.

The section from Smiths Falls to Ottawa (and east of Ottawa) is one of the few parts of the current VIA Rail network that the agency actually owns. And it will also be one of the most critical parts of the HFR line. At Smiths Falls, trains going to Ottawa via the Lakeshore services are going to join with HFR trains and use the same line at that point. Depending on the final design choices, only some of the Toronto to Montreal trains may go through Ottawa. But it could well be all of them, resulting all the HFR traffic, and some lakeshore traffic, using that one section of the line.

In some regards, this will be a fairly straightforward part of the network to upgrade. Level crossings are already signalled and gated, and throughout much of its length, the corridor runs through flat, relatively easy to build in terrain. A lot of the key elements are already in place so in this case a “put another track to it” approach would actually work super well.

While this section of VIA owned track, just east of Smiths Falls, may not have a rail bed reading and waiting for track to be laid down, that doesn’t matter. The line is pretty much straight and flat until the city limits and the terrain should make it relatively easy to widen the corridor to allow for a second track and all the required supporting infrastructure.

Grade separating this section from day one might not be an unreasonable expense. There are a number of crossings that are close enough together one of the two could be deleted. Farm crossings are close enough to roads that access corridors next to the rail line could likely be built for a decent price. And within the urban part of Ottawa, there are not many level crossings left to deal with. For a line that could be the busiest part of the network, it could be one of the sections worth going all out on straight away.

Just west of Barrhaven (Ottawa), is an example of how two crossings that could become one without a major impact for people in the area. All it would take is a road next to the rail corridor and that would leave one less crossing to manage. These are the kind of “easy” choices that people on the HFR team will start with to help simplify the rail corridor, especially if a section is being considered for full grade separation. Image via Google Earth.

The concept of scalability that has been described isn’t a theoretical, untested approach to moving a network from antiquated to increasingly modernized. The GO train network, since 2006, has been the poster child for exactly these kinds of strategies, with a carefully though out, iterative strategy to move lines from what were in many cases only slightly better than goat paths with a rail line next to them, to what will soon be fully electrified, double tracked, fast and frequent running. The full details were covered in a previous article from this site on the evolution of the GO train network.

There is a song and dance that has to be played in terms of balancing what aspects beyond the basics get added, as value for money propositions are continually examined and weighed against each other. But it is absolutely possible to make an iterative approach to the HFR network successful.

Attempting to unravel the unknowns and wildcards of HFR

Currently there are no major changes planned (at least publicly) for the urban Ottawa portion of the line, beyond electrification, and possible double tracking. But Ottawa, being the Nation’s Capital and having a lot of Federally owned land, is where one of three recent plot twists in the HFR proposal comes into play. That first wildcard that will be looked at is the role that Transit Oriented Development (TOD) on federal land could play.

This is something that has only officially come to light this past March 2022 when information relating to the start of the procurement process was released. In Canada, TOD is nothing new. In fact In cities like Vancouver and Toronto, around Skytrain, subway, and increasingly GO stations, it is has become a central part of transit expansion and modernization, with developers increasingly paying for updated or new stations themselves. It is is becoming standard for major urban rapid transit projects.

Lincoln Station in Coquitlam, on the Skytrain station, offers a good example of how transit oriented development has become a critical part of transit projects. Most new stations will see towers much taller than these, but the idea and spirit is the same…when possible, integrate the building of new transit and new housing from the start. Image via BC Business.

At the federal level however, neither VIA nor the government, have ever really done TOD before. In fact there has been shockingly few developments on federal lands despite the fact that a number of their landholdings are in prime, urban territory. Astute followers of Ottawa will probably point out that the NCC has engaged in TOD with LeBreton Flats, but they are separate, anti-democratic agency, from the federal government. The feds themselves were the primary party behind Wateridge Village on the former CFB Rockcliffe site, but there is no transit involved in that project. The track record thus far is not encouraging.

On the left is one of the many renderings of a fully built out LeBreton Flats. On the right is the actual state of LeBreton Flats, 17 years after the opening of the new War Museum kicked off redevelopment in the area. To make the situation even more depressing, just to the north of Lebreton, a huge redevelopment on the shores of Gatineau and La Chaudiere Islands, which started a decade later, is now outpacing the NCC run Lebreton. Left image by Claridge Homes via Global News. Right image from 6/2021 via Google Earth.

Trying to find geodata that accurately maps out all the federally owned land in Canada is not easy. There is plenty of data for National Parks, Indian Reserves (that is still the name used in official Government of Canada geodata), and other odds and ends. But trying to find mappable data for its commercial holdings is a real struggle. There is some data for land and buildings owned by the National Capital Commission (NCC), but it is only viewable online. But with a good knowledge of Ottawa, it is possible to at least make note of some of the larger plots of federally owned lands that are either directly beside the rail line, or in areas next to the Confederation Line where a trip to a train station would be anywhere from 5 to 10 minutes. Within the city, there are many opportunities, and even the NCC has sold off small plots of land to developers over the years, so they would likely be willing to get in on the action to some degree. What it could look like outside of Ottawa… that is a lot harder to get a sense of.

Views of some of the various federal and NCC properties throughout Ottawa. The top left shows the Ottawa Station area, with the beige overlay being NCC owned properties. Top right is the Confederation Heights area with many office in the park buildings, and also next to the VIA line and the shitty O-Train line. Bottom left is an under-utilized area of land in Gloucester (just north of Blair Station on the good O-Train line). And bottom right is the infamous Tunney’s Pasture, one of the most prime pieces of property in all of Ottawa being absolutely wasted on parking lots. Top left image from NCC data via ArcGIS. Remaining three images from Google Earth.

Compounding the lack of data on the scale of suitable federal lands across the whole length of the HFR line is that there are a lot of unknowns about the general plan and strategy for HFR and TODs right now. In fact basically everything is unknown. There is no idea what the overall scale they are looking to achieve is. No clue if it will be a developer gift, or actually used to address housing affordability. No idea about how the revenue generated from it will be used to fund the project, or if it will even go to the project and simply be a bonus for investors. So it could fall anywhere in between remarkably progressive and a game changer for the housing affordability, to developers rolling around in free cash (the latter is probably much closer to what the outcome will be). Either way, it is story to keep on an eye, though mostly for how wrong it could all go.

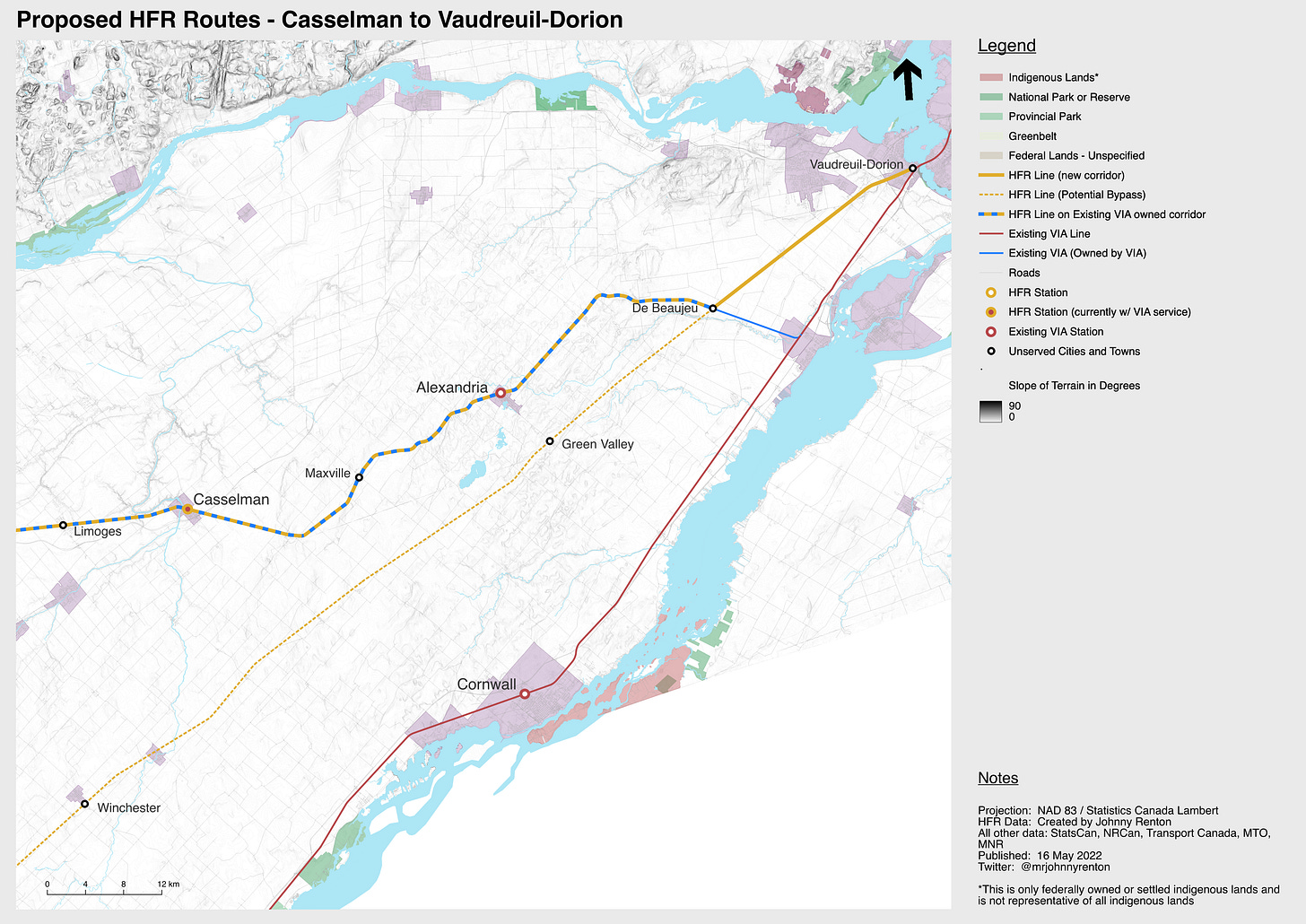

Once the line leaves Ottawa, which it does in short order when it heads east from Ottawa Station, it comes across another lengthy straight stretch, in this case one that is about 40km in length. It has a relatively high density of crossing at 29, of which zero are currently grade separated. And it runs directly through the communities of Vars, Limoges, and Casselman at the end of the section. The track and right of way is owned by VIA and overall it should be pretty easy to add additional capacity through this section.

The corridor is reasonably wide for the sections that are right in the communities themselves. This should make it easy to mitigate the effects of HFR through towns like Vars and Limoge, which will be crucial because this will be a very busy section of the line with potentially higher speeds than are seen today. If quality of life can’t be maintained through these towns, it will be out of laziness and disregard, not because it’s super challenging to do.

Looking west on the existing VIA Rail line through Limoges.Having this relatively wide corridor should make it much easier, and cheaper, to both upgrade the line and implement mitigation options to reduce the impact of increased, and faster, trains through the community.

On the surface, the corridor from Ottawa to to edge of Montreal might not seem all that exciting. Some small towns, a lot of farm land… probably seems rather uninteresting too many people. Except for the fact that this is a region which is growing at a rate that is often well above the national average of 5.2% (for the 2016 to 2021 census period). Ottawa itself grew by 8.9% in that timeframe, and could quite easily see its population rise to 1.3 million by 2036 (and that is just Ottawa, that does not include Gatineau which forms the second half of the National Capital Region). Just outside of Ottawa the town of Limgoes grew by 8.1% over the same period, and Casselman was even higher with a rate of 11.6% . As the line approaches Montreal it runs through the city of Vaudreuil-Dorion which topped all of the previous places with a growth rate of 13.5% and could easily be a city of 65,000 - 70,000 by 2036.

While places like Caseelman and Limoges are small at the moment, development is starting to pick up. In Limoges there are plans for at least 3 new subdivisions of around 958 homes, and those were just what was approved over a one year period from late 2020 to October 2021. In Casselman there is a plan for a 600 unit subdivision, and equally as interesting, a 540,000sq/ft Ford Motor Company distribution centre is now under construction and will empty around 150 people. Because of its location near the 417, and being semi-in between Ottawa and Montreal, Casselman could see additional distribution facilities set up, which would only boost the need for even more local housing, in addition to being a commuter suburb for Ottawa. If you are curious how much those seemingly boring industries can alter a city, just take a look at Mississauga or Brampton.

As is sometimes the case small towns are small until one day they are not. Once an area falls into a major cities commuter shed, its growth can take off very quickly. From the urban edge of Ottawa to the urban edge of Isle Montreal is only about 130 km via the current rail line. In just a few decades the regional and commuter connections in between the two cities could start to become a central function of the line. It shouldn’t be hard to accommodate that change, and there should be agreements and understandings in place that if VIA isn’t going to provide that service, someone can.

Once the line leaves Casselman it does get a bit quieter. The route goes through towns like Maxville and Alexandria, both of which have seen their populations stagnate or decline slightly as aging populations outpace younger people moving in, or sticking around. Much of that trend is tied to an important factor in the life and times of these towns and that is the changing nature of farming in Ontario, and all across Canada for that matter.

Casselman and Vaudreuil-Dorion is the last relatively straight forward section of the route before entering Isle Montreal. Worth noting is the bypass that can be seen on this map (and the previous one). This will discussed later but it is one of the 3 wildcard factors that are at play with the HFR project.

Consolidation in farming is a trend that has been going on for decades…since at least the 1950’s actually. Bigger farms are needed in order to remain financially viable. In the prairies, where farms were already much larger, the trend has been far more pronounced, with the average farm size increasing from 550 acres in 1951 to 1784 acres in 2016, or 324%. In Ontario the change is not as dramatic, with the average farm size in 1951 being 139 acres and 249 acres by 2016, an increase of 79%.

However the impact it has on communities in Ontario, and in Quebec, is still very real. Farm consolidation means less people over time have a reason to stay in the communities since many people sell their farmland and are no longer attached to the land they once made their living off of. And so as is more often than not the case, young people simply never take up the family tradition and move out, leaving one less long term resident, and resulting in a very slow decline in population. But the farmland still remains and as a result they still impose specific needs relevant to HFR in the form of farm crossings.

These have been casually mentioned before and there is a reason for that. For a long time, essentially since the start of railroads, they have been a staple in rural settings. It was relatively easy to get them installed if you needed one since all they required was some wood between the tracks and a pretty basic sign (in some cases it wasn’t even a cross hatch, just a small black and white private crossing sign).

This is what most farm crossings look like. Some of them are not even signed with cross hatches and stop signs. These are not great for cars, but for farm equipment, they are just fine.

They had two purposes. To allow farm equipment to get from one field to the next through the most direct route. Or in some cases they were driveways that actually lead to peoples homes, or ancillary farm buildings. In the case of driveways these fall under the category of private crossings which may or may not be able to be accommodated in the same way as the farm variant.

This is a driveway, on the CN line just east of Belleville, which actually crosses 3 incredibly busy tracks. In the near future this will need to have signals updated to include gates, as will all private crossings on the HFR line. But if sections are to be grade separated, then these become a lot more challenging, and in the case of homes not attached to a farm, may even require expropriating the property.

On lines where you have perhaps a few freight trains a day plodding along these crossings are not much of a concern. Yes the heavy farm equipment can sometimes take a while to cross. But trains aren’t clipping along at a speed where a stalled vehicle, even if a train is a few kilometres out, can easily result in an accident. But a 150 car freight train doing 80 to 90km/h, or a passenger train doing 160km/h or more, is a much different story. Accidents can be catastrophic and the margin for error is much narrower. Over time, as more lines found speeds increasing, so too did the concern over safety.

That is why on November 2014 Transport Canada implemented new rules around crossing protection. Some of the rules came in to effect immediately when it came to new crossings. But for existing ones, like farm or private crossings there was a 7 year timeframe for them to be updated (which has since been extended, in part due to the pandemic, but also because of the scale of the project). There is a variable set of criteria to determine which crossings need to be updated. But in general if a line has design speeds higher than 41km/h for freight trains (49 km/h for passenger trains), or has more than one track at the crossing, or has an additional siding track within 30m of the crossing, it needs to be updated to an automated system. While the federal government does have a program in place to help with cost of having those systems installed, this has meant that farmers are often saddled with an enormous cost to keep their crossings.

Along the HFR line there are not a particularly high number of farm or private crossings until the line heads east of Casselman, at which point they ramp up quickly and become the dominant form of crossing type outside of the urban areas. Due to farm consolidation, it is likely that many of these crossings can simply be deleted as there might be multiple crossings on what is now land owned by a single farmer. Where the challenges arise are the ones that need to stay.

There are a few options. One is to simply upgrade them to automated signal systems, which is the strategy taken across many farm crossings in the prairies. However, because there could be a desire to grade separate the line in the future, the goal might be to eliminate as many as possible straight away. One strategy that can be employed is building access roads next to the rail corridor so there is a public right of way to access fields. Not always a cheap option, but one that is possible.

When there are level crossings it is easy enough to ensure they can accommodate the larger size and width of farm equipment. But if grade separation is done, it has to be able to accommodate the largest of farm machinery, which is likely going to mean wider bridges and a slightly more expensive structures (a two lane bridge with narrow shoulders means a single combine will take up both lanes and block oncoming traffic). There may even need to be grade separated farm crossings in some cases. Solutions do exist. But running higher speeds trains through active, highly productive farming communities is not as straight forward as it seems. And if the project wants to garner some rightly deserved hostility towards it in a hurry, then failing to meet the specific needs of farmers is probably the fastest way to do it.

Why not use the Lakeshore corridor?

Once the line gets to De Beaujeu indications are that VIA will shift back onto the Canadian Pacific corridor and take that all the way in to Dorion-Vaudreuil. This is not the route VIA currently takes. Right now it goes on a 9 km trip down the last section of track it owns to the CN lakeshore corridor (which runs along the St Lawrence at that point), and heads into Montreal via that route.

It might seem odd to not use a section of track that it owns, but there is a reason for this. Once the VIA line merges into the CN line it would have to mix with freight traffic, which is the exact problem they are trying to move away from. So, one might ask, why not just build dedicated tracks in the CN corridor, like the they are doing in the Canadian Pacific corridors, instead of abandoning a section of track they already own? In fact, why not just build in the full length of the lakeshore corridor in the first place?

The simple answer is because CN has no interest in letting that happen. In fact up until the past 4 or 5 years, Canadian Pacific had no interest in working with passenger railways either. What caused the company to so radically change course? Who knows. They haven’t really publicly stated why, but they have likely realized leasing out unneeded corridor space could generate some good revenue for them. What is known is that the change of course has already had a radical impact. GO’s Bowmanville extension is making use of the Canadian Pacific corridor from Oshawa onward, and emerging plans to modernize the Milton line similarly will take place in one of the company’s previously off limit right-of-ways. A cross border link between Windsor and Detroit, operated by Amtrak, checked off one more requirement (on a very long and challenging list) when Canadian Pacific agreed to let them use the tunnel for passenger rail service (just 2 years after they bought the tunnel outright for their own freight projects). For VIA, HFR couldn’t have happened without Canadian Pacific’s new found co-operation.

Without the option of at least using some of the CN corridor, a modernized lakeshore route would have to be in an all new right-of-way which would be incredibly expensive. There are some parts of the Canadian Pacific mainline that run parallel to the existing VIA route, which could potentially be used. However even that has its own challenges.

The corridor itself is interesting because although the population is much more spread out, there are actually more people living between Pickering and Cornwall than there are in Ottawa. 1.17 million people in 2021 to be exact, and growing at a rate of 7.5%. VIA ridership numbers stations in that stretch of population was 561,323 in 2019. Though this is lower than the 779.697 that departed Ottawa that year, improving access for the suburban cities of Pickering, Ajax, and Bowmanville would likely do a lot to bring the two numbers much closer together. The cities and towns along the lakeshore corridor should not be dismissed simply because they are not an amalgamated population blob like Quebec or Ottawa.

But even if CN would allow VIA to build in its corridor there are many challenges that would lie ahead. The line is a busy freight corridor, and in addition to traffic heading to ports in Montreal and the Maritimes, or onward to Western Canada, there are 42 freight customer along the line between Pickering and Dorion-Vaudreuil which results in 35 sidings/branches coming off the mainline. A dedicated corridor could not conflict with those movements meaning many fly-overs or fly-unders to stay on the quiet side of the track, or avoid crossing the sidings at grade, would be needed. There is also going to be the need to grade separate even more crossings, given that traffic would rise to about 75-80 passenger and freight trains per day once a dedicated line opened. And it would only rise from there.

It might be easy to just dismiss freight railway needs. But Canada has some of the highest per capita use of freight railways in the world. CN itself is the third largest railway in all of North America. The role they play in moving goods is critical, and under appreciated. Ensuring their existing operations, and any future expansions, are protected, is a must.

These are just a few of the challenges that a lakeshore corridor modernization would face. They are not exactly insurmountable, but they add up to a very costly endeavour. When it is all said and done, the cost of a modernized lakeshore line (similar in design and spirit to HFR) would likely be as expensive as the current HFR project from Toronto all the way to Quebec City. Even if it was an option that could be picked from, it would be debatable if it would be the right one to do for the first intercity rail modernization project. Though it should still be done at some point and this might be the one of the few corridors in Canada in which a case could be made for investing serious amounts of money to build the majority of it to high speed rail standards.

Once the HFR route leaves Dorion and starts to head towards Iles Montreal the CN and Canadian Pacific lines converge (for a while). And this is where the chaos that is Montreal begins.

The Montreal challenge

In recent years of the project very little information about what could happen to HFR through Montreal has been given. And there is a very valid reason for that. The situation on the island of Montreal is an absolute fucking disaster.

This has been the strategy for Iles Montreal and Iles Laval. Should work out fine though. Image from South Park.

The ridiculousness of the situation is exemplified by the fact that instead of someone, anyone, building a new tunnel through Mont Royal in order to provide enhanced service, everyone seems to be trying to figure out how to cram everything through century old infrastructure. People who want better VIA service hate REM for taking the tunnel. People who like REM don’t care about VIA’s plans. No one wants to spend any money, even though it is going to have to be done. It’s all incredibly stupid.

But that is far from the only issue. The passenger rail network is an antiquated mess. As it stands today trains heading to the south shore, on what should be an incredibly busy and viable route to Mont St Hilaire, have to cross a 150 year old, single tracked Victoria Bridge which is not only shared with CN and part of its mainline to the east coast, but even has a drawbridge when taller ships need to pass through the St Lawrence Seaway. There are two passenger stations 500m apart with most of the EXO commuter trains going to Windsor Station, while some EXO trains and VIA (and now REM), use Central Station. Commuter trains coming from the North and East take a long route around the mountain instead of a tunnel being built so that they can avoid that and probably save a good 10 minutes on each trip.

In Toronto there have been serious, forward thinking efforts to modernize regional passenger rail (ie GO) services, which have had the money to support them. In Montreal… not so much.

Even with financial backing, and it will take a lot to fix the mess that is the rail network on the island, there are no easy answers. There has been little public information in recent years on what approach might be taken, so there isn’t really much else that can be said right now. Montreal and the North Shore will just remain a giant question mark for the time being.

The importance of the suburban station

Even if the specifics are uncertain, Laval is going to be an important station on the HFR network. It will make the service vastly more accessible, and desirable, to those who live on the North Shore. One of the most under appreciated aspects of rail service is how much more attractive it can be if you are close to a station (a station that is 10 minutes away is better than one that is 50 minutes from you). And for residents of Laval, that is very much the difference between using a local station, or having to drive to a metro and then take that to Central Station (or god forbid, having to drive all the way into Montreal).

According to the 2021 Census, Laval had a population of 438,366. So the potential for strong ridership is there. The idea that adding a suburban station can help attract an all new customer base isn’t just theoretical. In 2001 a second station was added to the Ottawa region on the northern boundary of satellite suburb of Barrhaven. Fallowfield, as it is known, actually became (according the 2019 numbers, the last non-pandemic year), the 8th busiest station on the VIA network, with 126,918 departures, and accounted for 16.3% of all departures in Ottawa. It played a critical role in the sizeable growth of VIA ridership in Ottawa since 2001.

Opened in 2001, Fallowfield Station was built at a bargain basement price of CAD1.2 million and has grown to the point of being the point of departure for 1 in 6 people travelling from Ottawa, and the 8th busiest station in the corridor in terms of absolute ridership numbers. Data from VIA Rail Canada.

But as good as Fallowfield has performed, Ste-Foy Station in the western suburbs of Quebec City has performed even better. In 2019 36.3% of all passenger in Quebec departed from the suburban station, and that share of passengers, like Fallowfield, has also been increasing over the years, up 5.1% from 2008.

A 5.1% increase in ridership share for Ste-Foy might not seem dramatic. But it isn’t insignificant and either and it goes towards demonstrating the continued and growing importance suburban stations can play when it comes ridership. Data from VIA Rail Canada.

Across the whole of the corridor, the 4 suburban stations of Fallowfield, Dorval, Ste-Foy and Oshawa were the 8th through 11th busiest stations on the network. And while ridership across the corridor as a whole grew by 48.8%, the growth of the above 4 suburban stations (plus the south shore station of St-Lambert), grew by 177%. Even if you take Fallowfield out of the equation and only compare the performance of stations that existed in 2001, their growth was still 99.1%, just a touch over double the overall corridor growth.

On the left is a chart showing the number of boardings at each of the top 20 stations and as can be seen positions 8 thru 11 are all suburban stations. On the right is the ridership growth for 5 suburban stations from 2001 to 2019 which have seen a lot of growth and represent a key ridership market which is still not even close to being fully served. Data from VIA Rail Canada.

As much as Canadian cities are urbanizing they are still overwhelmingly suburban. Better serving (ie directly serving) these parts of the Montreal and Toronto has the potential to tap into a lot of ridership. This is why a station at Eglinton in Toronto will be important, and why a station in Markham, at the edge of the GTA before HFR starts to head into the countryside, should also be seriously considered.

Fallowfield Station also illustrates another point, which is sometimes travel time reductions can be achieved just by having a better station to go too. A train going from Ottawa’s primary station to Toronto Union might take 2h50 or 3h00 on the HFR network. But if someone can catch a train in Barrhaven, it will mean the actual travel time by train will probably be reduced by 15 minutes, give or take, along with a shorter trip to the station itself. For those people, a trip to Toronto could be 2h45 or maybe even 2h35 depending on the stops. Like items that end in 99 cents, having the travel time of a train trip to Toronto be advertised as 2.5 hours (if they could save another 5 minutes on the trip) for those in the southwestern part of the Ottawa, becomes an enticing proposition (same is true for someone able to use a station in the Markham area to get to Ottawa).

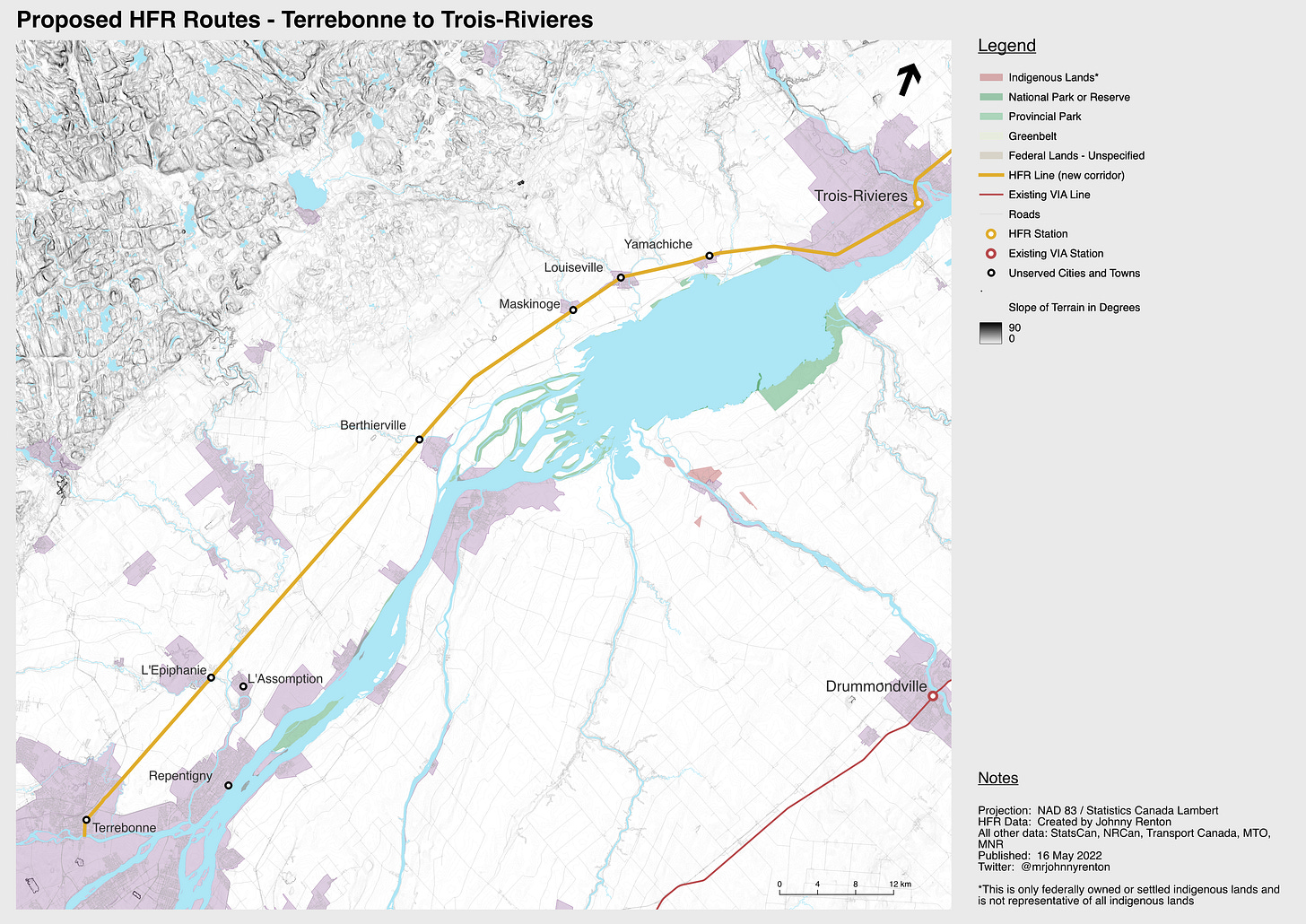

Once the line leaves Iles Laval it very quickly becomes very straight. Along the length of the HFR network this is the longest straight section at around 60km. And it ultimately goes 80km in total before encountering a curve that might restrict super fast running speeds.

Straight. Flat. Relatively simple and easy terrain to build on. This is the line, looking west, from Ste-Genevieve-de-Berthier, roughly half way between Laval and Trois-Rivieres. There are certain challenges, such as managing the 160 farm crossings on the section from Terrebonne to Trois-Rivieres alone, and quality of life concerns with the line passing through the heart of numerous communities. But a new track built with scalability in mind has a lot of potential through this area.

However, this section also has an incredible number of farm crossings, along with regular road crossings. That will probably make it cost prohibitive to fully grade separate the line and bump up running speeds on day one. But it does mean that an incremental approach towards removing level crossings could easily open up that opportunity in the future.

This section of line also brings up a relatively big failing of HFR. If you look at some of the most recent maps for the HFR proposal, it doesn’t show any stops between Laval and Trois-Rivieres, which is a distance of around 140km. This isn’t because the line travels through remote hinterland. Many towns, and even cities, exist along the way. VIA has tried to cover their ass by including the asterisked comment *additional stations may be added…..* but publicly they haven’t given any indications that they are seriously considering other stops beyond canned responses and lip service.

This is one of the recent maps released showing the HFR route. Definitely not a lot of consideration for the small or rural towns. Of course they say more stations could be added after community consultation, and some probably will. But it is rather embarrassing that most of those communities will have to fight for something that should really be part of the plan from day one. Image by VIA Rail Canada from Daily Hive.

When the line leaves Iles Laval it skirts along the edge of Terrebonne, a city of 119,944, as of 2021. A little further east it runs across the northern edge of L’Assomption, which in 2021 was home to 23,442 people. Further down the line you come across Berthierville, home to 4386 people, and the Gilles Villeneuve Museum (a must visit place for any F1 fans). There is Maskinonge, a town of a few thousand people, which is just down the road from Louisville, a town of 7340 people, before the line heads into Trois Rivieres.

Once the line leaves Iles Laval and heads toward Trois-Rivieres it passes by, or comes close to, quite a few built up areas, many of which are not exactly small either. Just leaving these populations on the table is one of HFR’s more egregious choices.

It highlights one of the biggest faults of not just HFR, but of pretty much all intercity rail proposals over the past 3 decades. There is a near total disregard for smaller cities and towns in between the major centres, which in itself is part of the broader problem of accessibility. Justified as a “prudent” strategy, it is really little more than an anti-rub, urban-centric attitude in action. Especially on a project like HFR, there really isn’t a justification for this to happen.

Imagine for a moment a new freeway is being built. It could be the upgrading of Highway 69 between Parry Sound and Sudbury to get rid of the often busy and dangerous two lane road that still serves some sections of the route. It could be Autoroute 40 between Laval and Trois Rivieres. Whatever freeway you pick, ask the question of whether one would be built that goes 140km without a single interchange. The answer is no, not a bloody chance. Freeways don’t have interchanges with every single road they encounter. But unless a freeway is going through completely remote territory, as in no roads, no people, just untouched landscapes, there are going to be interchanges at least every 10 - 20km, even if it is sometimes serving roads with limited traffic or tiny communities.

However, when it comes to building modern, intercity rail lines, which are the freeways of passenger train service, there is not the slightest bit of hesitancy to have a line run for 140km without a single stop, even when there are communities directly along its path. Between Terrebonne and Trois Rivieres, A-40, which essentially parallels the HFR line, has 22 interchanges, while the proposed rail line will currently have 0 stations.