GOing Urban Part 1

How two decades of quiet incrementalism is transforming the GO train network into the most modern passenger rail system in North America

When most people hear about transit projects, it tends to be the largest, flashiest, and as a consequence, most expensive ones. The mega projects, like Skytrain extensions in Vancouver or new subway lines in Toronto, are eye catching for their audacity, size and the impact they will have on the cities. But sometimes massive public transport network changes are the result of dozens, even hundreds, of smaller and often unnoticed projects that, over time, add up to radical change.

For 54 years GO trains have been shuttling commuters across the Greater Toronto Area. The service is about as utilitarian as you can get. The now famous bi-level cars were not designed with aesthetics in mind, to put it politely. It was about maximizing capacity. Stations were simple and barebones, with more attention being paid to parking than passenger comfort. The green and white trains may be a staple for those living in the GTA, but few will wax poetically about the style and sophistication of GO trains (save its iconic logo).

By the end of the 2020’s much of the service, and the infrastructure, will bare little resemblance to what it looked like at the start of the 2000’s. Its transformation can even be seen today, as it reaches beyond the GTA and is on the borderline of becoming not just a regional network, but a provincial one. By the end of the decade it will become North America’s most modern passenger rail network and the story of how that was accomplished is fascinating, instructive, and under appreciated.

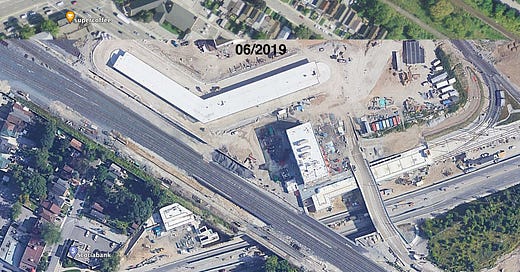

Satellite imagery, via Google Earth, showing the Georgetown South Corridor (part of the GO Kitchener line) where it crosses Eglinton Avenue, as it was in Sept 2009 (top image), and June 2019 (bottom image). What was once a brush filled corridor with just a single track for GO service now has a modern, 4 track line. In the bottom image not only do you see the new Mount Denis GO station under construction, but the storage yard for the new Eglinton Crosstown LRT line.

GO TRIP

It was on 23 May 1967 that GO started passenger rail service on the Lakeshore line from Pickering to Burlington. It was a low cost experiment ($9.2 million in 1967, or around $75 million in 2022) to see if rail service could help accommodate the growing commuter traffic in the Greater Toronto Area. Money was spent on some new trains, bus shelters to serve as ‘stations’, and little more with the trains being tossed down an existing rail line along the Lake Ontario shoreline. It proved successful and within 4 months service went from 9 trains a day in each direction during weekdays to 22.

What GO service looked like in 1971. When launched there was little done to actually build modern stations. A bus shelter near an old, often decaying, CN train station is what most passengers got. Train cars were also single level, something that would change by the end of the 1970’s.

From its opening to the start of the 2000’s GO slowly expanded service onto other lines. In most cases it was just a few trains a day during the week, with no service on the weekend. Trains mostly ran on tracks owned and used by freight companies like CN or Canadian Pacific and this severely restricted opportunities for service increases. While there are aspects of the first 38 years that some might find interesting, it is in 2005 when the story of modern day GO really begins to take shape so that is where the focus will be.

In 2005 GO TRIP was announced. It was a $1 billion (in 2005 dollars) investment in GO train infrastructure and facilitated the first rail-to-rail grade separations (seen below), added track to parts of the network, and helped usher in some new line extensions. GO TRIP was a relatively modest investment, but it was also the largest one up to that point.

The West Toronto Diamond, as it was when the two rail lines crossed level with each other (top image) and once the two lines had been grade separated (bottom image. This was one a few rail-to-rail grade separations done at the time which helped increase safety, speed and reliability on the lines. Images via Canadian Consulting Engineer.

It also set in motion a pattern of incrementalism that would be key to GO train growth. Removing level crossings and replacing them with over- or under-passes is the kind of low key work that GO would undertake for well over a decade (and still continues to do today). The projects were relatively small and largely flew under the publics radar, unless you lived in the immediate area. But their importance cannot be understated. Grade separations allow for safer, faster, and more reliable train service. And as these projects were done, they also planned for the future. If a line was going to have a second track in a decade or two, bridges would be built to that standard, so that there would be no need to go back and ‘upgrade’ these crossings at a later date. Despite a tendency often seen to save money today, even though it can push up overall costs when completed down the line, GO by and large bucked this trend.

GO continued its incremental approach in other ways as well. It would purchase rail corridors, as they became available, or when the price was right. This is critical as once GO owned a corridor, it could upgrade tracks solely for its own benefit, and have full control of how many trains were run, and when. Sometimes it was simply adding a siding to allow for a little more capacity and reliability, and other times it meant double tracking for some distance, or in the case of the busy Lakeshore corridor, adding a 3rd or 4th track where needed.

And the new east rail maintenance facility in Whitby was built to quickly accommodate electrification. Anyone taking a GO train past it can see the concrete pillars just waiting for the masts, along with other design details, that will accommodate the overhead wires that are coming in the future.

Perhaps the best way to understand the approach taken is with the below map. It shows all of the projects undertaken by GO from 2006 to 2019.

Map showing all of the infrastructure projects undertaken by GO/Metrolinx from Jan 2006 to September 2019. Created by the author.

While there were some sizeable projects, like the Georgetown South corridor upgrade, it was mostly a series of smaller individual projects that added up to the much larger network change.

And then there are the Union Station upgrades, which will be discussed later but are one of the most important elements of the GO expansion strategy. A 20 year project in itself the transformation of this hub is both remarkable and and absolutely central to the future success of GO, and public transport in Toronto in general.

2019 was a turning point in the story of GO. At that point the focus was on completing projects underway, and starting to deliver increased service. While there were many small increases in this time some in particular stand out. 7 January 2019 saw the introduction of one round trip, each weekday, from Union to Niagara Falls, marking the services move past seasonal service. In August 2019 15 minute service, for most of the day, was introduced on the Lakeshore line. On 7 Aug 2021 GO also introduced hourly service to Hamilton’s Harbour West station. And to many peoples surprise on 18 October 2021 GO introduced one weekday round trip to London, Ontario.

However, this didn’t mean the end of infrastructure investments. In fact it was quite the opposite.

Next top, the big show

Transit agencies love releasing big, bold visions of the future. They draw all kinds of lines on a map, create fancy renderings, and show a future of travel that feels seamless and idyllic. GO was very good at this in the 70’s and early 80’s. There was the GO Urban plan, a network of rapid transit lines in Toronto, based on maglev technology. Then you had the GO ALRT network of the late 70’s, based on the ICTS technology that would power the Scarborough RT and Skytrain in Vancouver.

Proposed GO ALRT vehicle (top image) and routing (bottom image). The program never really got off the ground, aside from some land acquisition that would eventually become part of the Pickering to Oshawa GO Train extension. In some ways SmartTrack and GO’s electrification will revive some of the core ideas of this project, just using a different technology. Images via BlogTO.

Both of those plans went nowhere and GO scaled back its ambitions, focusing on traditional commuter/passenger rail systems. In 1978 GO’s direction was, for better or for worse, secured as a traditional commuter service as it introduced the use of bi-level coaches. It would be many decades before the slightest deviations from this strategy would be seen.

When GO introduced bi-level trains into service there was a lot of excitement and fan-fare surrounding them. Not only was the design first used by GO (they were made specifically for the agency) but they would eventually be used in dozens of cities all across North America as the idea of modern passenger rail was largely abandoned in favour of quick, cheap solutions. Images via Metrolinx and Toronto Railway Museum.

In 2008 GO resurrected the tradition of overly ambitious plans in the form of ‘The Big Move”. It was a bold sweeping vision for what the network would look like in a few decades. Lines would be electrified, there would be 6000 trains heading to Union Station each week, versus the 1000 or so at the time. It would be faster, more frequent, more modern, and serve more destinations both within or outside the GTA. It was a real beauty. A classic transit agency over reach for the ages.

Then something funny happened. The plan actually started to pan out.

By the mid-2010’s there was a cultural shift in taking place. Unlike in previous decades there was public and political support for GO expansion, as well as other transit projects, and voters were putting money behind them. It was something that everyone wanted which made it much easier for the projects to gain traction. Even Ontario’s Conservative party who have, since June 2018, gotten into the transit building game carrying on with almost all the projects set in motion by the previous Liberal government.

New projects had been starting every year since 2005, corridors were being scooped up as they became available, and slowly but surely the seeds for monumental change were being laid.

GO projects like the Davenport diamond grade separation, upgrades to the Bayview Junction and pocket track upgrades at Aldershot station (which are allowing drastically increased service to Hamilton), the Lakeshore West and East upgrade programs, and additional tracks in the Georgetown corridor, were undertaken or have just begun. These works followed in the GO tradition of quiet incrementalism. But it was no longer about aiming for a target a decade or two out. These were in many cases the final rehearsals and tune ups before the big show.

And in 2022 that big moment arrived. Several new projects have, or will, start construction that not only ratchet up the scale of investment in the GO train network, but will leave many parts of the network electrified, and fully modernized. The continued upgrades to Union Station will expand waiting platforms and finish its transformation into a high capacity passenger rail and intermodal transit hub. SmartTrack stations will help transform GO into a real inner city transit alternative within Toronto, as well as benefiting regional and inter-city services.

And then there is the show stopper, the ON-Corridor upgrade program. At $15.73 billion dollar the project isn’t just the largest in GO’s history, but the single largest public transport project ever undertaken in Canada.

What will result from this projects is substantial. 200km of new track across the existing network to double, triple, or quadruple track corridors, and 600km of electrified track (which will result in 262km of the route distances being electrified). This means all new faster, modern, electric trains will be required as well. There will be new stations, a new inner-Toronto service that falls somewhere between GO and the cities subway lines. It means that Union Station could see 50 - 60 trains an hour during its busiest time, and provide a much more comfortable, accessible and safer experience for passengers, even with the radically increased passenger numbers.

A new version of the GO Expansion map, shown a dozen or so paragraphs up, shows the projects that have started since October 2019 to today, as well as ones which will be starting by the end of 2022. Even in just under 2 1/2 years, during a pandemic, the amount of work being undertaken, and the continued use of small, incremental projects, is pretty remarkable. As this article was being written news came out that ground had broken on the Ontario Line, starting with the new Exhibition Station that will serve both the new subway line as well as GO. The steady stream of GO projects, in many different stages, coming from Metrolinx is quite something.

Map showing the most recent GO Train network infrastructure projects, along with those that will be starting by the end of 2022. Even as large as the ON-Corridor Metrolinx began preparatory work through the Lakeshore East & West Improvement Projects in order move some aspects of larger modernization project forward faster. Those are in additional the the many smaller, incremental projects undertaken each year. Map by the author.

The end result will see most lines (except for Milton and Richmond Hill, which will be discussed later) having all-day, two way, 15 minute service, with some sections within Toronto being even more frequent. Travel times in most cases will be reduced as the new electric trains will accelerate faster, across an upgraded infrastructure.

Remarkably, this isn’t all that is on GO’s radar. Small, but important projects, like adding a pocket track at West Harbour station in Hamilton is likely to happen in a few years and will allow for faster trips to Niagara Falls, and perhaps open up increased service opportunities. On 10 August 2021, Federal Transport Minister Omar Alghabra announced funding for an upgraded Milton Line that would see all day, two way service. While details are still limited given that funding was announced before Metrolinx had a plan, the Milton Line has long been the holy grail of GO due to its incredible ridership potential. The challenge has always been Canadian Pacific’s reluctance to allow increased passenger rail service but given that agreements are being made with GO and VIA to build their own tracks in other Canadian Pacific corridors, a similar agreement likely forms the basis of a Milton Line modernization plan. And in January 2022 the province directed Metrolinx to move forward with the business case for a new line to Bolton.

These are a just a few examples and some, like a Bolton line, likely won’t move forward until the current slew of under construction projects are completed. But Metrolinx isn’t stopping after 2030. There is a lot more on the horizon.

Lets do the Canadian thing and compare our public transport to Europeans

Canadians often seem like they have a desire to feel inadequate. Despite totally different histories, growth patterns, and geography, there is still a need to compare ourselves to European counterparts when it comes to public transport. Being aspirational is fine but often it is a silly exercise. Having dunked on others it is time to flip flop and say that ‘this’ case is different because it gives an idea of the scale of change that is coming to the GO train network.

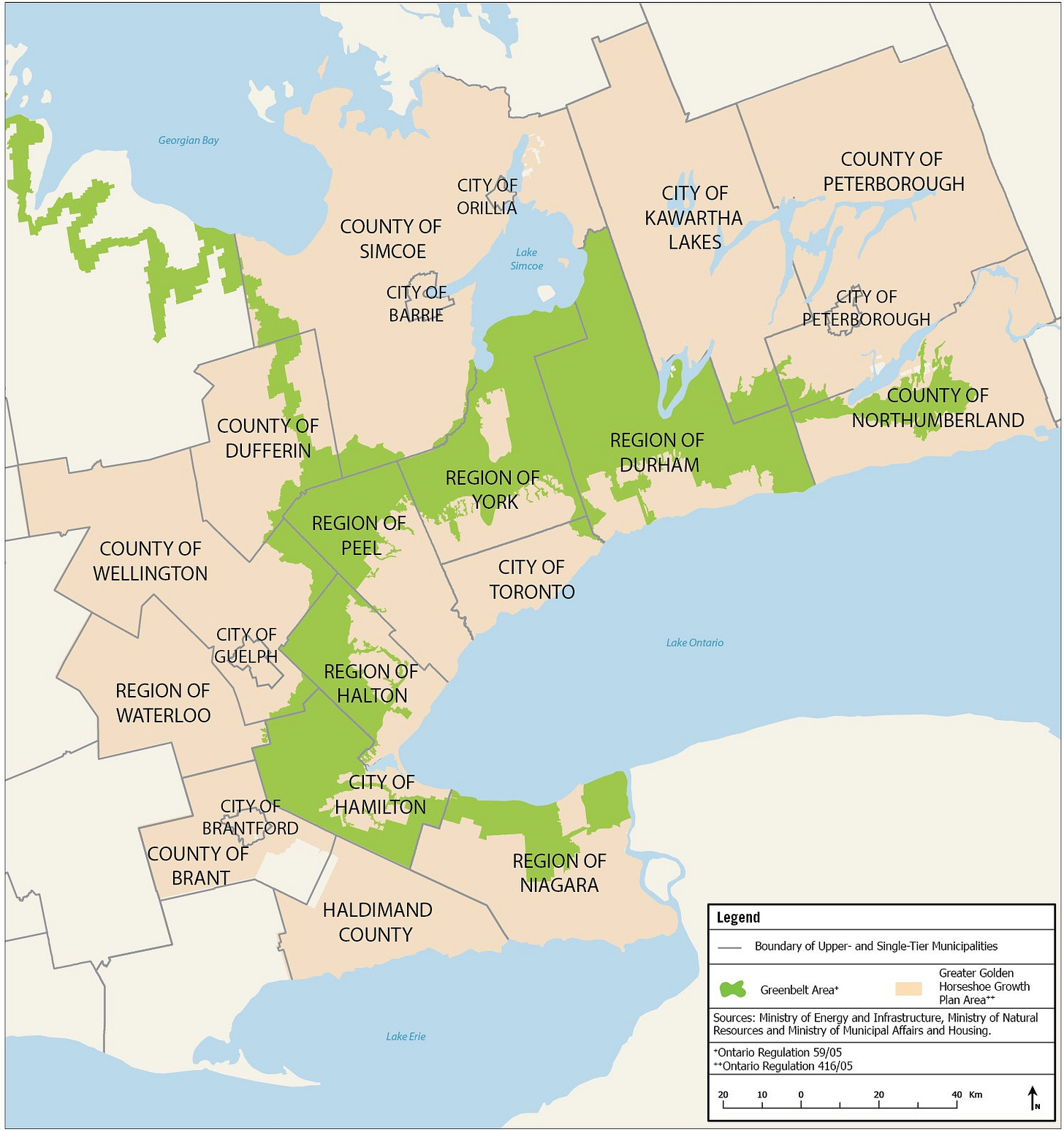

To give a sense of the coverage GO will offer, taking a train from London to Bowmanville (currently the longest E-W direction of the network) would cover a distance of around 280km. Going from Barrie to Niagara Falls (in the N-S direction) would cover around 335km. The area that the GO Train will cover (as planned) is roughly the same as what is known as the Greater Golden Horseshoe. This includes not only the GTA, but Niagara Falls, Kitchener-Waterloo, Barrie, and even Peterborough. The only part of the GO network that is not included is London. In 2021 the GGH had a population of 9,765,188 and London was home to 422, 324, according to Census Canada data, giving the probable 2031 GO train service area (GGH+London) a population of 10,187,512 million. Given current growth rates of around 5% every 5 years, this area will likely be home to around 11.3 million people in 2031.

A map showing the extent of the Greater Golden Horseshoe (GGH), which is comprised of the GTA along with all the additional municipalities that border it. The GGH is home to around 26% of all Canadians, a percentage that is continuing to grow. Image via Government of Ontario

As a comparison, the Netherlands is 312 km in the N-S direction, and 264km is the E-W direction, or 41,543 km2 (the GGH has a total area of 31,562 km2 so when the London region is added in the geographies of the Netherlands and GGH are relatively similar). Currently the Netherlands has a population of 17.4 million people, and given its relatively modest population growth, it will probably be around 18.4 million in 2031.

Nederland Spoorwegen (NS) is the Dutch national railway service. In 2019, the last pre-pandemic year, NS saw 1.3 million trips per day, which translates into 474.5 million passenger trips that year. And while NS is a national carrier, providing intercity and international service, it also takes care of all the commuter rail needs of cities like Amsterdam, Rotterdam, and Utrecht.

In 2017 annual ridership on GO trains was 57.4 million people. Given to how Metrolinx reports GO ridership, a break down according to train, bus, or Union-Pearson Express (UP) isn’t always available. But based on an overall GO network growth of 5.3% from fiscal year 2017-18 to 2019-20, this would put GO train ridership for 2019 at around 60.4 million people.

Using 2019 data, GO train ridership works out to 5.93 trips per person in the GGH+London, while NS sees 27.3 trips per person. This means the GO train network carries just 21.7% of the passengers that NS does, relative to their populations. That is not particularly impressive, but lets fast forward to 2031.

The table below, from the 2018 GO Expansion Full Business Case Executive Summary, shows their ridership projections for 2031, which is estimated at 178.7 million riders.

Ridership projection table from the November 2018 GO Expansion Full Business Case Executive Summary, including breakdowns by line.

It is important to note that this number might actually be an underestimate. No where in the report is SmartTrack mentioned, which makes sense as at the time it was very much a separate City of Toronto initiative. After several iterations it has become a joint GO project, and according to Metrolinx themselves, they estimate that it will bring 110,000 new daily riders to the rail network, with some of those almost certainly being GO riders as opposed to SmartTrack riders. There is also the Milton Line, which includes projections based on the status quo. A modernized Milton service, which also serves Mississauga, would almost certainly result in an additional 20-25 million trips each year. The actual ridership of the modernized GO network in 2031 is most likely going to be 200 million, and could even be a touch higher than that.

What this all means is that by 2031, per capita GO train ridership levels for the GGH+London (at 2031 population levels) could be around 17.7 trips per person. Given that the Netherlands already has a well established, mature, rail network, the trips per person is probably not going to rise much higher. If ridership on NS increased 2% each year, and with modest population increases, NS might achieve per capita ridership rates of 30.8 trips per person. While GO’s per capita ridership might still seem low, that would shift the GO train network from carrying 21.7% of the passengers that NS does, to 57.4% of their total, in just 12 years.

Unlike NS, there will still be sizeable opportunities for growth on the GO network. Much will depend on Metrolinx’s ability to buy, or build dedicated tracks, in corridors such as the Richmond Line (which will continue to see just 5 trains a day), the Kitchener to London and Hamilton to Niagara Falls corridors, along with the previously mentioned extension to Bolton. And depending on the agreements made between VIA and Metrolinx for the urban sections of its new HFR line, new services to southern Markham and Peterborough might be possible.

Infrastructure upgrades are the driving force of this initial ridership boost. But there are two other factors at play in GO’s future, especially down the line. Those centre around the primary hub of the network, and how Canadian cities are developing, growing, and becoming more urbanized. And one location has all of these forces coming together.

Union Station

Central stations always play a critical role in regional and intercity rail networks. But even then, Union Station’s role in the modernization of the GO rail network is much greater than it first appears. Up until the early 2010’s, Union was a rather dank, uninspiring place to be. Sure the Great Hall was pretty, but much of the station was dim, cramped, with the only redeeming quality being a Mmmmuffins outlet for high sugar, super delicious treats as a you passed through.

While development north of the station has generally always been strong, the south side of tracks was different. The waterfront, which at one point in time was the home of industry and shipping, was a veritable ghost town by the 1970’s. It was little more than a sea of parking lots among vast expanses of rail yards. No doubt many have seen the aerial comparisons, but it is worth showing them again just to get a sense of the scale of change that has happened in the area. Change which still continues today.

View of downtown Toronto in the late 1970’s (top image) and 2019 (bottom image). The rail yards and two massive parking lots are now gone, as are most of the surface parking lots along the waterfront. The area still continues to grow today. Top and bottom mages from UrbanToronto.

In 2009, as the waterfront area was slowly redeveloping, the Union Station Revitalization project began. Pretty much every last meter of the station is set to be modernized by 2030. The exterior was cleaned, the Bay and York concourses were completely gutted and redone, there was better passenger flow, lighting upgraded, and several dozen food options were added, along with seating, in all new food courts. There was a new glass atrium in the centre of the train shed which allowed light to actually flow onto the boarding platforms.

Union Station over time. The first 3 images show the station as it existed in the late 90’s and early 2000’s prior to renovations, including one of the last Mmmuffins. The new concourses are modern, brighter, bigger, and separate food court traffic from passengers travelling straight through the station. Heritage aspects of the building have also remained and been renovated, where appropriate. The difference is night and day. Images 1 and 3 via BlogTO, image 2 via Myla U on Twitter, and images 4 through 6 via the author.

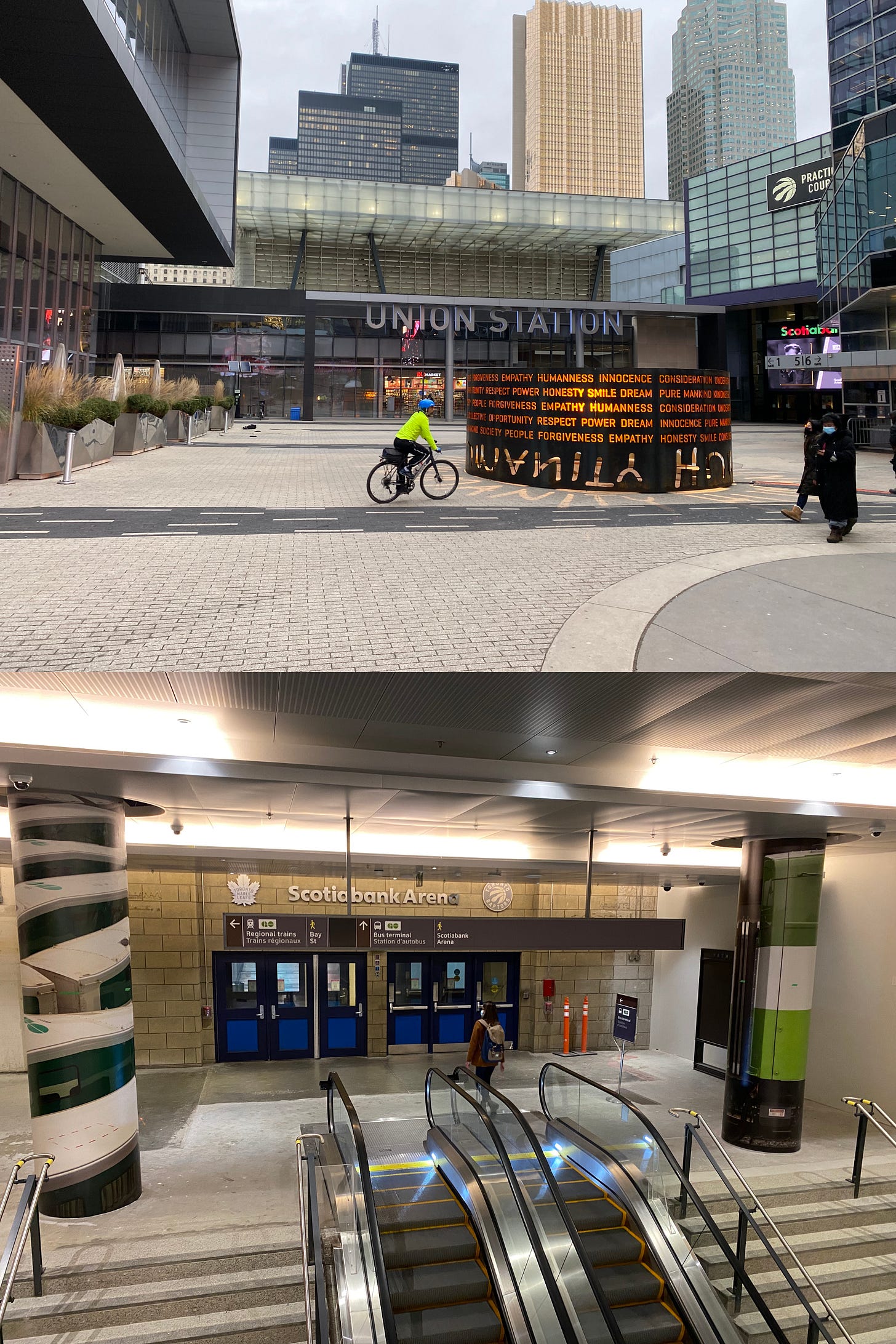

There were new entrances at the southern end of the station that opened onto Maple Leaf Square in the all new South Core district. Where as Union once turned it back on the waterfront, it was now fully engaged with it, along with the Scotiabank Arena, home to the Maple Leafs and Raptors.

Improved access at the southern side of Union Station has been crucial not just for the vitality and viability of the station itself, but for the development of the South Core district. It is a small, but critical detail in Union’s revitalization. Images via the author.

And in Dec 2020 an all new bus terminal opened, which meant that intercity buses no longer used a separate, somewhat dilapidated facility a few blocks away. They, like GO buses, are now part of the Union hub. While the bus terminal may not have its own food court one can walk, indoors, for just a minute or two, to either the Bay or York concourse to grab a bite to eat there, just as rail, streetcar, or subway passengers might do.

Waiting area for the new Union Station bus terminal. It might not be fancy, but its location within the Union complex means GO bus and other intercity bus services are now equals among trains, the subway, and streetcar connections. Image via Metrolinx

The tracks themselves have been subject to modernization as well. Switches and signals have been upgraded to accommodate more trains. And on 16 February 2022, the expansion of Union Stations platforms officially began. This will get rid of narrow, cramped platforms, and elevate them to a wider, more spacious standard common in most European rail stations. It is a small, but absolutely essential change to enhance passenger comfort, and allow for safer, faster boarding to get trains in and out of the station quickly.

A platform at Union Station, barely wide enough for a stairwell, on 1 March 2022 as works crews began removing track for the platform expansion project (top image) and a rendering of a newly upgraded one (bottom image), with more than enough room for an elevator and passengers to safely walk or wait on either side of it. Top image via Metrolinx and bottom image via Infrastructure Ontario.

In total, around $2 - $2.5 billion will be spent to modernize Union Station, from top to bottom, inside the station and out, and on the tracks and signals leading up to and through the station. That might seem like a lot but consider this. Union Station already sees more trains everyday then it has at any point in its history, even during the height of intercity rail travel in the 1940’s. The plan to quadruple that by 2030 simply would not be possible without these upgrades.

Two other elements are important to Union’s role in the growth of the GO train network. The first is due to Toronto having been lucky enough to end up with one central, non-terminal station used by all passenger rail services (the name Union comes from the unification of various passenger rail companies into one station).

Without getting too far in the weeds on the details, trains can drive in, and if they want, like on the Lakeshore Line service, simply drive through. No backing up like they would have to do at a terminal station, which can mean significant time savings. And because all GO and VIA trains head to Union (and to a much, much lesser degree, Amtrak and eventually Ontario Northland), no matter what direction they are coming from, transfer to another service is quick easy if one train doesn’t get you to your destination. Compare this to cities like New York, London, and Paris, which have 2 or more train stations, and where transfers can mean taking a metro or subway across the city. And with connections to buses, the Yonge-University subway, UP, and a few streetcar lines, it provides arriving passengers with the kind of transportation options that make public transport desirable. It is everything a fully inter-model transportation hub should be.

Build it and they will come

The final element to GO’s future success goes beyond transportation and into development. As was seen above, the growth around Union station over the past decades has been extraordinary. Only Vancouver can rival the trend setting that Toronto’s central district has had on the urban renaissance taking place in many Canadian cities. It has created new destinations, like offices and what not, to attract people to the core, along with tens of thousands of places for people to live. And it has set a new standard for the kind of development that is taking place around other GO stations (and rapid transit stations in general).

For much of its life GO train stations were typically surrounding by parking lots and giant parking garages. A legacy that lead to Metrolinx/GO Transit becoming one of the largest parking lot operators in North America. Even Union Station itself was largely devoid of people actually living nearby (save the remarkable St Lawrence neighbourhood). That is changing. Within Toronto its stations are now hubs for massive urban developments. Mount Denis, which will open as an interchange on the new Eglinton LRT line, and Mimico are already seeing new development take place. New stations at King-Liberty and St-Clair-Old Weston will take advantage of growth already underway. The Transit Oriented Communities program is one that will see developers cover the cost of new or upgraded stations, in exchange for better transit access, and ultimately higher real estate prices. The new East Harbour, Park Lawn, and Confederation station in Hamilton are all being funded through this program, as well as the upgrades to Mimico.

Two of the most high profile developments taking place next to GO stations within Toronto. The top image shows the Cadillac-Fairview East Harbour station development, which will see 10 square feet of office space and 4300 residential units, and is just one of the multitude of developments set to take place in that neighbourhood. The bottom image shows the 7500 unit development at the former Mr. Christie factory site, next to the future Park Lawn GO station, and is also just one of many developments in that area. Top image via Globe and Mail and bottom image via Livabl.

This trend isn’t just taking hold in Toronto. One development being proposed for Innisfil, Ontario is particularly audacious. While still in the early phases of planning/approvals, meaning it might not happen, it is nonetheless worth a quick look at the Orbit. This is a new community, centred around an upcoming Innisfil GO station, which will be located on the soon to be electrified and modernized Barrie line. It would eventually be home to around 150,000 people and is designed to take advantage of the GO station as the heart of the city. The renderings are wild and if it were to built as shown it would be the most fascinating and futuristic development in all of North America, let alone Canada. Whether it happens or not, it demonstrates that GO modernization is fundamentally changing how cities are being planned and designed in the GTA.

Presenting, the Orbit, the plan for a new community in Innisfil, Ontario, centred around a modernized GO train service. Who knows if this will ever be built as presented. But its less about the architectural vision and more about the fundamental change in thinking about how communities, even those well outside major cities, can be centred around passenger rail and active transit instead of cars. Images from Barrie Today, The Toronto Star, and Global News.

Development patterns do not change over night. Projects take time to design, get approved, sell, and ultimately build. It will likely take 2 decades before the full impact of development around GO stations is seen. But every new home that goes up within walking or biking distance almost certainly adds more ridership to the GO network. Every rapid transit line that feeds a GO station makes taking the train that much more convenient.

Excluding development around Union Station, there is almost certainly going to be well over 150,000 residential units proposed or under-construction within walking distance of GO stations in the 2020’s alone. That may even be an under-estimate. And as that development pattern takes hold, it has the potential to bring over 1 million additional people within walking distance of a GO station by 2040, creating an entirely new type of rider that will dramatically boost passenger levels. In fact if those 1 million people took just two round trip rides on a GO train each month, that alone would boost ridership by 48 million trips a year.

To some, the idea that 1 million additional people could live within walking distance of a GO station by 2040 might sound far fetched. But this is actually quite likely. And the trend is so important it is why part 2 of GOing Urban will go deep into the details of development around GO stations.

There are negative consequences to be wary of. Without a real shift in government policies to deal with the housing crisis, only a small minority of people might be able to afford living near a GO station, potentially turning rapid transit and modernized passenger rail into a luxury item. Those implications are beyond the scope of this article, which is why part 3 of this series will be dedicated to them. Ensuring that the positive impact TOD’s will have on the GO network are not negated by negative social impacts is crucial to ensuring these investments are not a wasted opportunity.

But what about people who are not travelling downtown?

Usually when there is organizational change the results are not much better than rearranging deck chairs on the Titanic. The case of GO Transit and Metrolinx is an exception and it is as much a part of the future success of the GO train network as the investments in infrastructure are.

Prior to 2008 you had two distinct type of transit agencies in the GTA. Municipal agencies, like the TTC or Durham Transit, which oversaw buses, streetcars, and local rapid transit, and GO Transit, who looked after regional trains and buses. One of the challenges that was being faced is that municipalities were no longer separate and independent when it came to transit. The Yonge-University subway lines were being pushed into the 905. Destinations, like Pearson International Airport, which is in Mississauga, needed to be as well connected into the Toronto Transit System as it was into Peel’s.

Metrolinx was thus created as a regional transit agency with a much larger mandate. It assumed the operations of GO, as well as taking over responsibility for projects such as the Eglinton Crosstown, Hurontario LRT, Finch West LRT, and Hamilton LRT, to name a few.

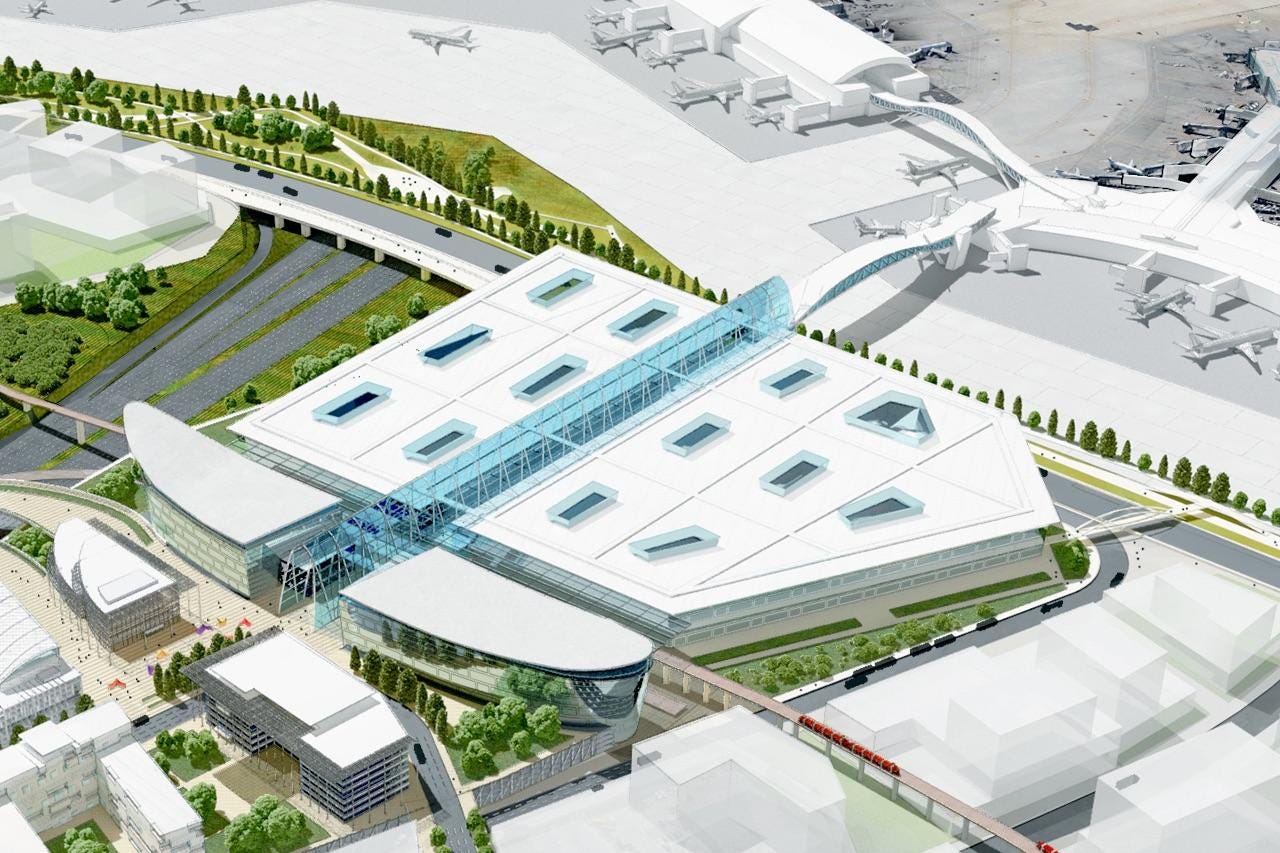

Why does this matter? Metrolinx has paid close attention to integrating its transit projects. When the Crosstown was designed, it included, from day one, new stations on the GO Kitchener and GO Barrie lines creating easy transfer points between GO trains and the new LRT line. The same is true of the upcoming Ontario Line which will have a station at the upcoming GO Harbour East Station, just east of Union Station, and at an all new Exhibition Station to the west. It can better facilitate the regions interest in the Pearson Union West project that could see UP, GO, Eglinton Crosstown, Finch West LRT, and the Mississauga Transitway serve an all new, dedicated transit station at the airport. It also allows for better coordination with VIA Rail, and the transit services run by the municipalities.

A proposed central transit hub at Pearson International Airport would integrate GO, UP, TTC, and other regional transit services into a single location. It is a hugely ambitious project with huge implications for regional transit and employment at the airport. A regional agency like Metrolinx is well suited to work with the GTAA to properly connect as many transit options as possible. Image via UrbanToronto.

It ultimately meant that GO trains were no longer going to be an island unto themselves and it creates what Metrolinx CEO Phil Verster calls the network effect, where increased connections create better options and services for customers. The rising tide of an LRT line helps do the same for the GO lines it is connected too. Without a regional authority operating across more than a dozen municipalities, public transport integration in the rapidly growing GTA becomes the kind of nightmare that rivals the bureaucratic shit show seen in the Ottawa-Gatineau region.

And this is truly opening up the GO train network to all new travel options. Weekend trains to Hamilton and Niagara create steady flows of people out of Toronto. A passenger who works at Yonge and Bloor, wants to go to the Science Center, or visit a friend in Etobicoke or Hamilton is seeing all new opportunities to use GO to get there, or get to a transit line that will quickly complete the final leg of their trip. It is a sign the network is changing and becoming more diverse.

The price tag of modernization

Building a modern passenger rail service isn’t cheap. Since 2005 up to the end of 2022 the known cost of projects undertaken or started will be $25.2 billion. Projects in which costs are unknown, be it because they were municipally lead, as is the case for some grade separations, small enough that they could come out of Metrolinx’s capital budget, programs like Lakeshore East Improvement where total costs are net yet determined, or projects under the TOC program, likely total around $1.3 billion (and that might be on the low side). The imminent Bownanville extension, and the likely Milton Line modernization will probably come in at $3 - $4 billion in total.

This means that by 2031 it is almost certain that in a 26 year period, $30 billion will have been spent on GO train network modernization, with the cost of new rolling stock not even a part of that equation. And given that other projects are likely to come online towards the end of the decade as modernization opportunities arise, be they new lines, corridor purchases, additional electrification, or a slew of smaller projects like more grade separations, the total could easily be in the $32 - $35 billion range.

If that price tag had been dropped at the start of the article, before the full story and magnitude of the project was known, it might have sounded outrageous. If someone had tried to propose the full scale of these modernization efforts all at once, it likely would have failed. If you had tried to get the same development benefits from stations that saw 5 trains a day, versus ones that will see a train every 15 minutes or better, it likely would have been a tragic endeavour.

But that price tag is the cost of developing a truly modern passenger rail infrastructure in Canada, and across much of North America. It is the difference between rusty, single track lines carrying a dozen trains a day through a corridor little better than a goat path, and networks that can handle a dozen trains every single hour which provide service that people actually want to use. It is the difference between a system that had a ridership of 39,640,200 passengers on its train services in 2005, and one that could see ridership levels of 200 million passengers in 2031, with much more room to grow beyond that.

This is what budget railroading looks like. Concrete bus shelters for stations. Single track lines. Uneven asphalt for platforms. This is fine for throwing a half dozen trains down the track each day or catering to people that can wait in their cars on a windy, or snowy day. But it is not sufficient to change transportation and development patterns in a meaningful way. This is the legacy that GO is leaving behind, but also requires serious investments to do properly. Top image is of Whitby Station in 1971 and is via Metrolinx. Bottom photo is the Stouffville corridor around 2010, prior to the start of modernization, via Chin Lee

Next stop, the rest of Ontario

As it stands today GO is still largely a GTA service. However, service to Niagara Falls and London, as limited as they are, is pushing GO closer to being a provincial train service. With VIA moving forward with its HFR program, it will start to reshape the Ontario passenger rail landscape in rather interesting ways. There has already been rumblings of GO being the primary provider of London to Toronto service on the northerly route through Kitchener, which makes sense given the highly urban nature of the line. It is known that HFR service will see Peterborough reconnected into the VIA network. With details still being worked out, questions have been raised as to whether this could open the door to some GO service from Peterborough to Toronto to better accommodate the commuter crowd that will come from that line.

Metrolinx has also become a partner with Ontario Northland on the proposed train service to North Bay (and potentially up into the Timmins region). While the trains would not be branded as GO, given that Ontario Northland’s brand is already well established, it could mean that infrastructure work that might benefit GO and Ontario Northland could be coordinated together, as well as designing a service that would take advantage of the GO train networks various local transit connections.

It will likely be at a decade before GO really starts to push the envelope of being a provincial rail service. Corridors will need to be purchased, or agreements made to build in right of ways owned by the railway freight companies. And the core of the network, Union Station, Lakeshore, the full length of the Kitchener line, even the Milton Line, will need to be fully modernized and in service before a more outward expansion can be seriously explored.

But the wheels are in motion for this to happen. And even without that grander outlook on paper, by 2031, the GO Train network will look, and function, like no other in North America. For many people it will have seemed to snuck up out of nowhere. But in fact it was a highly calculated, carefully thought out series of hundreds of incremental projects over the course of 2 and 1/2 decades that will have gotten it there. It is a model that other cities would do well to understand, and emulate. And it has the potential to start rivalling some of the European networks many people in Canada look up too. By 2040, GO’s rail network could reasonably approach per-capita ridership levels that are 80% of that of the NS; an achievement few would have thought possible even a decade ago.

Incrementalism can be a powerful tool when it comes to building modern passenger rail in North America. A single track line is fine as an interim solution, or at the end of a line before rural landscapes turn to uninhabited hinterland. But to make this strategy work, investments need to be made, even for small projects, that accommodate the future, as well as current needs. And no other agency has done this as well as GO/Metrolinx has.

In part 2 the full scale the investments in GO’s modernization, as well as other public transport projects, are having on urban development around their stations will be explored.

If you want to find me on social media you can do so @Johnnyrenton.bsky.social on Bluesky. If you have any thoughts or feedback let me know in the comments.