GOing Urban Part 2

How the plans for modernized GO train service is already changing the urban landscape around its stations

For almost 5 decades, the words ‘GO trains’ and ‘urban’ were like oil and water. The stations were more often than not surrounded by the asphalt paradises known as parking lots, with perhaps a giant parking structure being the only significant structure on site. Even a majority of the stations in urban settings, such as Eglinton or the Hamilton GO Centre, were not seeing the same urban renaissance that other parts of Toronto and the GTA were experiencing.

Guildwood parking lot/GO station. It is understandable if someone cannot image one of GO’s station being anything but this. This is how most have looked for many decades. Image via HousingNowTO.

Towards the end of the 2010’s this was changing. New local rapid transit projects, such as Eglinton Crosstown, Hurontario LRT, and the Ontario Line, are under construction (some will open this year, others in 8 years) and will feed even more transit services into the GO train network. Some new stations, like Liberty Village or Spadina - Front, that are within Toronto will tap into existing development hot spots. Others, such as East Harbour, will help create all new, highly urban, development nodes. And this prospect of fast, modern, all day 15 minute service is spurring new construction and urbanization plans not just in Toronto, but all through the GTA.

Across North America, there is no other region that is set to see the scale of urban change that the GTA and parts of the Greater Golden Horseshoe will over the next 2 decades. Even the perennial urban champion Vancouver will find it hard to keep up. The change will be truly awesome but it is a not a turn of events that materialized out of thin air.

A golden age of grime and poster stores

The story of GO’s urban awakening begins in the late 1980’s. The prior decade had been brutal for the urban cores of Canadian cities with most seeing significant population declines, or at best, simply plateauing. From 1971 - 81 Metro Toronto (now simply known as Toronto) as a whole experienced some growth, increasing by 47,666 people, but the central part of the city (what was then the borough of Toronto), saw its population decline by 113,074 people, or 15.9%. But by the end of the 80’s the first signs of urban recovery were taking place, though it wouldn’t be until 2011 that the former borough of Toronto would match the the population levels seen in 1971.

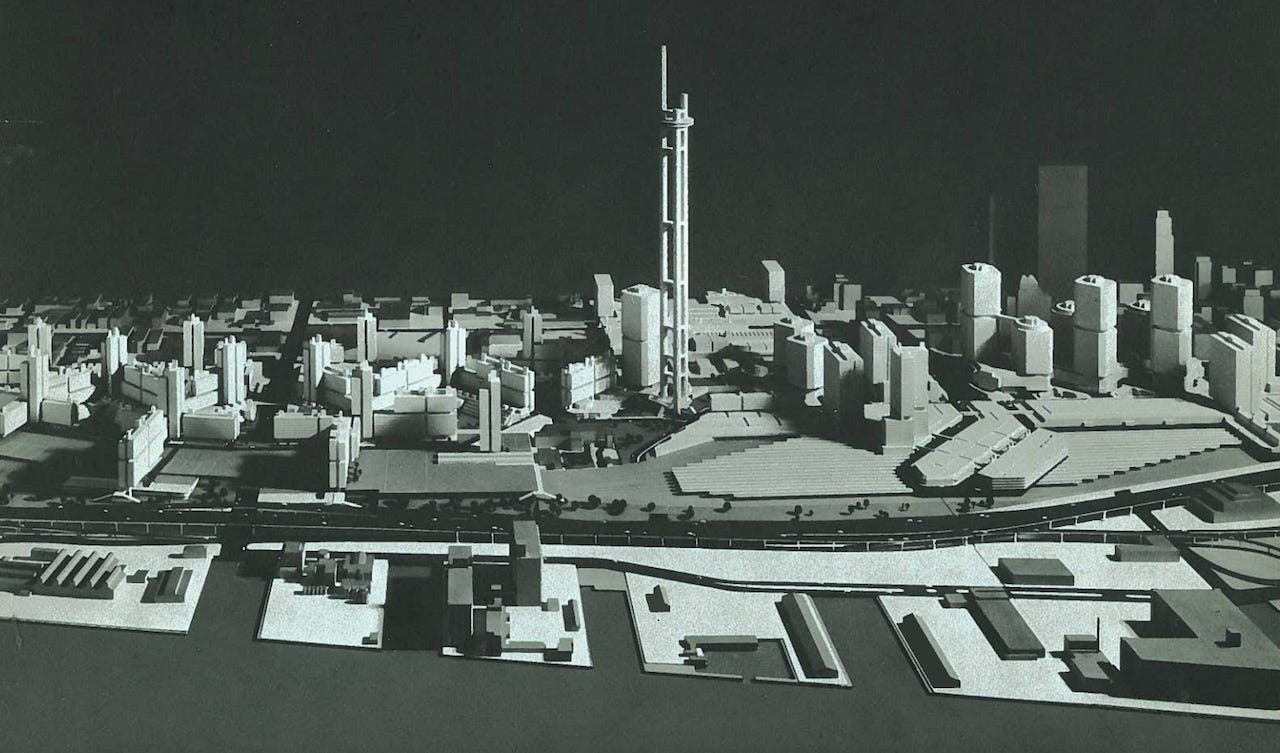

As downtowns and the urban centres of cities all across Canada struggled throughout the 70’s and 80’s, a litany of urban redevelopment schemes were explored and in some cases undertaken. Often times, as is the case with most mid-sized cities in Ontario, they tried to fit indoor shopping malls on razed downtown blocks in order to attract people back to the core. With the exception of the Eaton Centre in Toronto and the Rideau Centre in Ottawa, most of those malls have struggled and often just ended up creating anti-urban dead zones. Massive redevelopment schemes, like the proposal by CN to demolish Union Station, realign its railway and develop over a rail yard that was to be decommissioned, were luckily defeated as the results would have been disastrous, and extraordinarily difficult to fix.

This is a model of the proposed redevelopment of the CN rail yards in downtown Toronto, including a very early version of a telecommunications tower. The plan is peak tower in the park, with suburbanized urban spaces. It was ultimately binned, including the demolition and relocation of Union Station, though a now iconic tower would be built with a much different design from the one above. Image from WZMH via Urban Toronto

There were some successes and one of the biggest of that era was the St Lawrence Market area of Toronto, just a hop, skip and a jump from Union Station, where a cooperative neighbourhood was created on former industrial lands. It has since become one of the most vibrant and beloved parts of the city. It was an outlier, and in many ways ahead of its time, but it was a reminder that Canadians still remembered how to build urban neighbourhoods that people love and care about.

The top image shows one of the co-operative developments under construction in the 1970’s, and the bottom image shows the David B. Archer Co-operative living its life in the 1980’s. Though the neighbourhood was still dominated by cars, the scale and simple styling of the buildings resulted in the kind of urban fabric that has made the area beloved and a highly desirable place to live. Images from City of Toronto Archives via BlogTO.

The 90’s was going to look very different and on the other side of the country the Coal Harbour development in Vancouver was a sneak peak into what was about to come. While it is often derided for being ultra-posh and a bit devoid of people, it was still a trend setting development. Right on the waterfront, within ear shot of downtown, it took a formerly industrial plot of land, and created a new neighbourhood. Its architecture was not award winning, but it was also not trying to mimic the city building of the past.

At the time Coal Harbour was built, almost no one would have imagined the impact this style of building and urban design would have on Canadian cities. This was a pivotal turning point for the urban centres of cities like Toronto and Vancouver. Image by Daderot via Wikipedia.

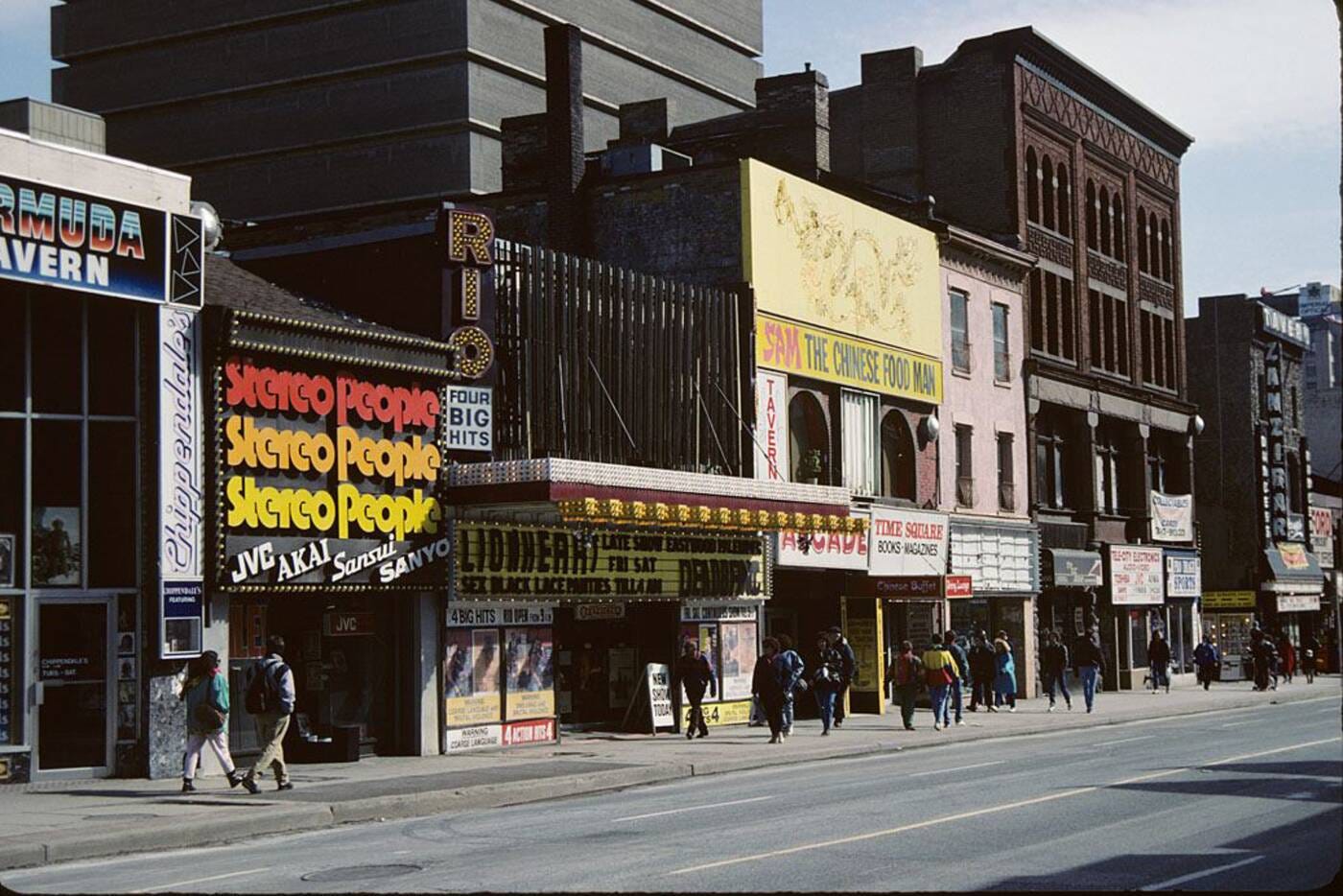

While the Coal Harbour development pointed to something bigger about to happen, Canadian cities in the 90’s were still more often than not defined by gaudy and tired streets. The kind of place were you went to on a Friday night to go to a peeler bar and grab a terrible slice of pizza before calling it a night. Surface parking lots and poster shops were as common a sight then as Starbucks and Shoppers Drug Mart are today.

Yonge Street in 1990’s. People will often wax poetically about the days when this street was low rent, low brow, and lined with stores with questionably sourced goods. And while there was something about the experience of walking down this street at the time, it wasn’t a pretty place, nor a place that had a mainstream appeal, save for the Eaton Centre and HMV. Image from the City of Toronto Archives via BlogTO.

Canada however, was changing in the 90’s. As free trade agreements were being signed, in particular the NAFTA agreement, the country was becoming integrated into the global economy well beyond its traditional natural resource sector. It would mean manufacturing was about to have a really bad time, but a newly emerging tech would start to rise (and then fall, and then rise again). The economy was growing stronger, with 1999 seeing an unemployment rate of 6.9% versus 10.7% just 7 years earlier in 1992.

This also ushered in an era where immigration flows were coming from many parts of Asia, the Middle East, and countries that had not usually been part of this movement. Most famous was the wave of people, and their money, from Hong Kong to Vancouver who were looking for a new place to live and do business before the territory was handed over to Chinese rule in 1997. But it wasn’t just the people that were different, it was where the moved to. Historically the urban centres had seen the bulk of the immigrant flow head their way. In Toronto it had been the Chinatown along Spadina, Greektown on the Danforth, and Little Italy on College. But now it was the suburbs, especially those built in the 50’s and 60’s, that were becoming enclaves for the newcomers. Surrey was becoming home to a burgeoning East Indian community, and in North York, a borough of Toronto, Iranian’s were establishing what would be colloquially known as Tehranto.

There was one more factor that was going to influence Canadian cities and that was Generation X. Among this group were people, from a diverse set of backgrounds, who had been born and raised in idyllic suburban subdivisions, or smaller rural cities and towns, who wanted nothing to do with that lifestyle. It didn’t matter that a place like Yonge Street was kind of trash and low brow. They were still urban places. And sometimes they were even places where you could live and not own a car. Young people wanted city life, and that was where they were headed.

Transit is dead. Long live the car

Despite the cultural and political shift that was brewing, the 90’s was perhaps the zenith of suburban development. You occasionally had some transit projects take place, such as a Skytrain extension in Vancouver, or the rather strange Sheppard Subway Line in Toronto. But more often than not transit was free to go fuck itself, as projects like the Eglinton Subway were cancelled, while highway projects like the 407 ETR, went full steam ahead.

A view of a newly opened Skytrain station in 1990. Even when transit was built in this era, it was often bare bones and cheap, as illustrated above by the station which could easily be confused for an elevated industrial building. Image by Alain M via Buzzer Blog.

GO didn’t fare much better. In 1993 there were service cutbacks on its train network which wouldn’t be fully restored until the end of the decade. As discussed in part 1 of this series, it wasn’t until 2008, with the release of ‘The Big Move’ plan, that there was even the slightest hint that GO wanted to be more than a parking authority and commuter service.

Quite remarkably this ‘drop dead’ attitude towards transit didn’t hinder urban growth. The trend carried on, with neighbourhoods that were already connected to long standing streetcar or subway lines being the first areas of activity. At that point most Canadian cities still had a plethora of surface parking lots to build on, so demand was easily accommodated, with little opposition.

By the 2010’s, serious investment in new rapid public transport projects began to happen. 2009 saw the Canada Line in Vancouver open, in time for the 2010 Winter Olympics. In 2011 the Eglinton Crosstown started construction, which was the largest public transport project at the time in Canada. The Yonge and University subway lines were seeing extensions beyond Toronto’s borders into the 905. Transit-mania was sweeping the country, and it was so heavily supported by voters that fewer and fewer political parties spoke out against it.

These investments, in conjunction with new official plans that put an emphasis on urban development around rapid stations kicked the urban revival into full gear. Yet one agency was lagging behind.

GO has entered the chat

Phil Verster became CEO of Metrolinx, the agency that oversees GO Transit, in October 2017. While the agency had big plans for the better part of a decade, and some of them were taking shape, there was one fundamental shift that had yet to take place, and it centred around their stations.

Whether it was Verster himself who steered the agency in a new direction, or if his arrival happened to coincide with a broader change in the agencies direction, is not really known (though perhaps this is clarified in an obscure interview somewhere). Likely it is a bit of column A, a bit of column B. But there is not much doubt that this was the time where GO stations as development locations, and conversely development locations being ideal candidates for new GO stations, began to take hold.

The second figure critical to this change was Doug Ford, who assumed office 29 June 2018. A champion of developers, his government has heavily pushed the Transit Oriented Communities program, which sees station upgrades paid for by developers in exchange for the ability to build higher density residential developments next to GO stations. While Ford was initially dragged for this strategy, in part because it lead to Confederation GO Train Station in Hamilton being delayed, its intended effect is now starting to be seen.

A rendering of the development planned around Mimico GO station as part of the Transit Oriented Communities program. In this instance, the program hasn’t simply resulted in a station being funded by the developer, but instead has blurred the lines between the station and the development itself. This approach is becoming increasingly common across the GO network. Image from VanDyk Properties via Urban Toronto.

This brings us to today, April 2022, where all of a sudden GO train stations, in particular those within Toronto and those with new or improved local rapid transit options, are becoming development hot spots in the same way subway, or metro, or skytrain stations had been for the past few decades.

Establishing what GO modernization has meant for the GTA so far

When it comes to determining just how large an affect GO modernization will have on urban development in the next two decades, it is critical to establish what is happening today as the baseline. How exactly do you do that?

First, you need to establish what is considered ‘walking distance’ to a rapid transit station. 800m (1/2 mile) is a number that is frequently used, and translates into a walk that is around 10 minutes. The reason for focusing on those people within walking distance is because that is the scenario, along with high frequency service, that makes urban living truly desirable.

From there, you need to determine how many projects are under construction, proposed (as in applications submitted to cities or municipalities), in the sales stage, or part of broader masterplanned development for an area (such as the plans for Downsview airport or the Portlands). To do that a number of sources were used. UrbanToronto was the primary one, but a number of other real estate sites helped fill in the gaps and provide additional data.

Sample of the spreadsheet used to compile data on proposed, in sales, or under construction residential projects, in this case for Danforth station. There is one column, for the price of a 1 bedroom unit, that is not yet completed. That is an important part of the story of the development taking place, and will be done for part 3 of the GOing Urban series. Chart by the author.

All of the data was entered into a spreadsheet (a portion of which is shown in the image above), which gave a number for the amount of development that was underway, or being planned, around the GO stations. To observe broader patterns it also made sense to map out this data, which will be shown in just a few paragraphs.

The other factor is determining how many additional people are going to be within walking distance of one of the new GO stations being built in already populated areas. For that, 2021 census data was used to determine a rough estimate of the density around the stations. If the census tracts totalled 4 squared kilometres, then population was simply divided by 2, since a walking distance of 800m gives a coverage area of 2 squared kilometres (with some slight adjustments made depending on how much of one particular land use the census tracts covered).

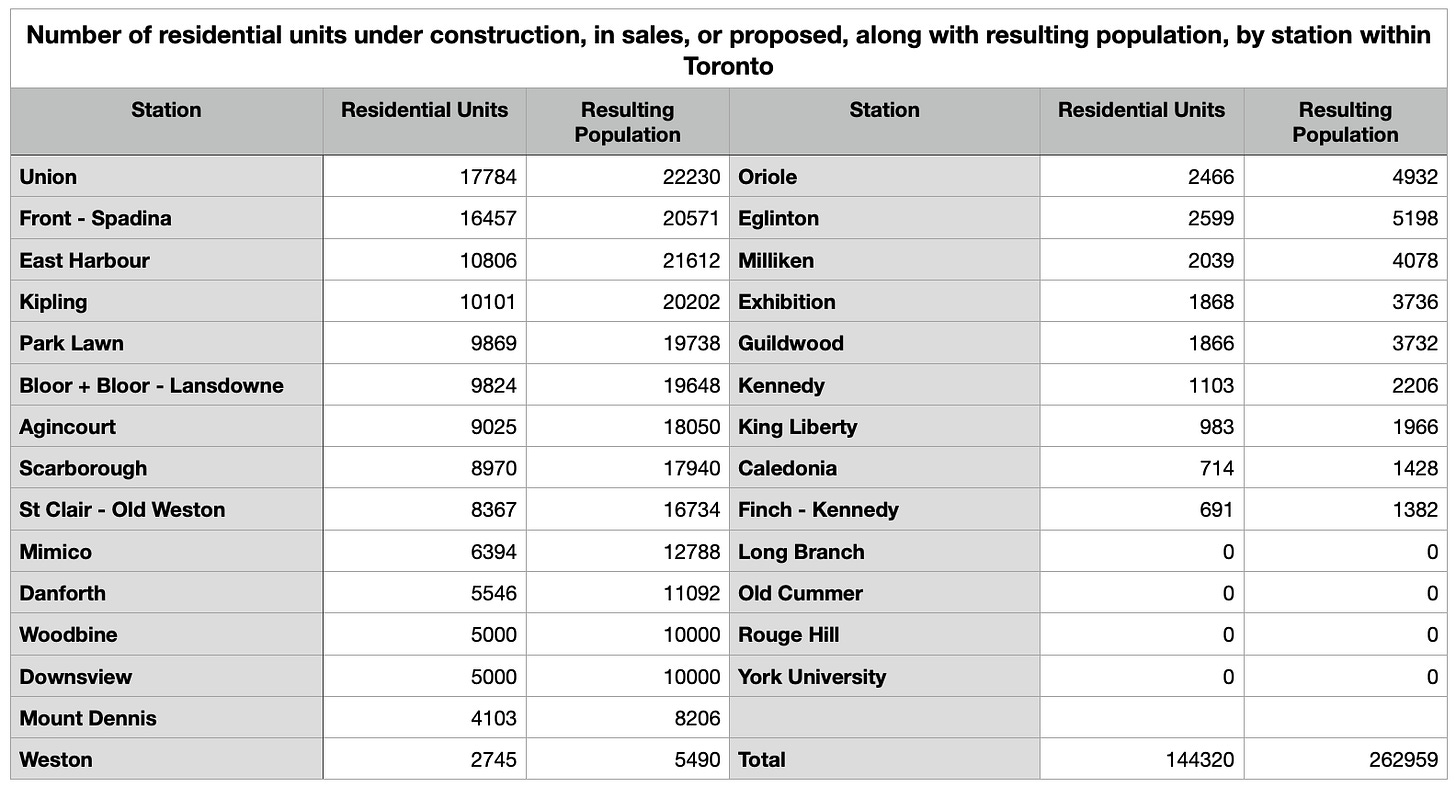

When its all said and done, what are the numbers that emerge?

The total number of residential units across the GTA that are under construction, in sales, proposed, or being planned is 199,735, which would ultimately house around 373,789 people. In terms of the number of people who will find themselves within walking distance of a future GO station (among the stations that are being built or in the advanced stages of planning), that number is around 111,346.

The above map shows the number of residential units in various stages of planning or construction. A number of patterns can be seen in this map, but the most apparent is the level of development within Toronto, or right next to the city, versus that further out in the GTA. Image by the author.

This means that as of 2 April 2022, there is already the momentum in place to see an additional 485,135 people across the GTA living within walking distance of a GO station. There are some small differences between looking at residential units versus looking at the population that will be generated (which includes the existing populations are added into the equation for the GO stations that are being built or planned). But the region wide trends are the same no matter which data you look at.

The above map shows the number of additional people who will be within walking distance of a GO station, be it from new development, or an existing neighbourhood getting a new station. Image by the author.

If this seems surprising, you’re probably not alone. That is an extraordinary number given that the modernization campaign is only just beginning. But going through the data in more detail offers some clear insight in to what factors are driving this growth.

Toronto and the power of multiple transit connections, empty land, vibrant neighbourhoods, and the waterfront

A little over 63% of all the new development being planned around GO stations, as of today, takes place within Toronto proper. And it should come as no surprise that Union Station has the highest number of units being proposed at 17,784. along with a station leading 10 office towers, of which 4 are currently under construction.

Ranked list of Toronto GO stations and their total number of under construction, in sales, or proposed residential units. Chart from the author.

These numbers around Union Station aren’t just achieved through the number of developments, but by the height of them as well. The average height of a condo tower in this area is just over 60 storeys, with two of them hitting 90 and 95 storeys respectively.

The top image shows the Pinnacle one project, and the scale of it, with the two tallest towers planned to be 95 and 90 storeys. The bottom image shows the Sugar Wharf Condo project in the foreground, with Pinnacle One just behind it. Even among the tall towers that exist in the area, these ones will stand out and provide 7349 residential units in total. Image 1 and image 2 via Urban Toronto.

Number 2 on the list is Spadina - Front station which is right next door to Union and captures a good part of the fast growing entertainment district. It is a good time to note that in the chart above, the formula for determining number of people per unit is different for Union and Spadina - Front than the rest of the stations. The standard formula, when a diversity of units in a building is considered, is that 1 unit will house 2 people. In the very centre of the downtown core, the dynamics of the housing market are a bit different. You have many of these units being purchased as short term rentals, which means you are not adding permanent residents. There also tends to be a higher number of units geared towards singles and couples as opposed to families. For this reason, 1 residential unit in the Union and Spadina-Front catchment areas is assumed to result in 1.25 people being housed.

This is why East Harbour, which comes in at number 3 on the list in terms of development, is number 2 in terms of the residents it will attract. This station is worth a look because it will be one of the most noticeable, and largest development nodes in the GTA. To the north of the station, about a 6 to 8 minute walk, is Queen East, a popular, and hugely desirable area that had already seen an increase in mid-rise (6-9 storeys primarily) development starting to take place on parking lots or redeveloped parcels. To the south is the Portlands development, which is a massive city of Toronto lead project that will turn a vast portion of the waterfront and former industrial lands into an all new urban neighbourhood.

A view down Queen Street East with a modern streetcar. For many people, streets like this are quintessential Toronto and the kind of places they flock to. Image via Pinterest (original source unknown).

The Portlands is absolutely fascinating, and will be a future article unto itself as the importance and scale of it is worth a proper deep dive. It has already sparked one concrete, high profile, proposal put forward by developer Cadillac Fairview. Not only will it see a dense cluster of residential and office buildings go up next to East Harbour, they will be constructing the station, at their own cost. It will be one of the first all new stations that will come out of the Transit Oriented Communities project. This one project alone will have an immediate impact on the area, with 4500 units, or 9000 residents. And for the final feather in the cap, East Harbour will also host a station for the new Ontario line subway, and include local streetcar connections as well.

The top image (submitted as part of a 2017 planning rational when Great Gulf was planning to develop the first section of the East Harbour area) shows the amount of land that will be developed south of the station as part of the Portlands project (anything north of the station will be regular parcel by parcel development as occurs in the rest of the city). Of note is that the East Harbour station would extend across the Don River, providing direct access to those in the Corktown Commons neighbourhood. The bottom image is a hand drawn view of East Harbour station over a local street and was included because this style of architectural drawing style is so delightful, under appreciated, and rare in an era of hyper real digital rendering. Images via Urban Toronto

It’s easy to see why East Harbour will be a development juggernaut. It has everything; empty land, multiple rapid transit connections, close to downtown, Queen East, and the waterfront (in particular the wonderful Tommy Thompson Park).

This is a common theme. Among the top 10 stations in Toronto 4 have subway connections, 3 have streetcar connections, with only 3 having bus service and nothing else. 5 of the stations are a leisurely stroll to the waterfront, 5 are within or border existing, well established urban neighboorhoods, and 5 have land suitable for 5000+ unit developments. Only 3 stations check just one of those boxes with the rest having 2 or more of those components.

What is happening in Toronto is not all that surprising. GO stations are simply becoming another collection of nodes for a two decade long building boom to capitalize on. Put another way, a development beside an inner city GO station is now just as desirable as one next to a subway station was over the past couple decades.

In the 905, the current scale of development planned is much more modest, relative to Toronto. But there are indications this is changing and that parts of the GTA could be on par with Toronto in the not too distant future.

More parking lots and emerging urban centres

On the surface, the 55,415 residential units currently being proposed, sold, or under construction, across the vast landscape that is the 905, seems rather paltry. After all, there are even more parking lots and low rise suburban buildings surrounding GO’s suburban lots, so these should be ‘the’ hot spots.

All of the GO stations, current, under construction, or planned, in the 905, ranked according to the number of developments being planned around them. Chart by the author.

Going back to the map that was shown earlier (and the chart above), there are a number of stations in which development is zero, or near zero. In a number of cases these stations do not represent a failure of municipal policy or lack of interest. Oshawa Station, for example, is perhaps the industrial heart of the eastern GTA with the GM Assembly plant as the anchor, and dozens, if not hundreds, of other businesses surrounding it, along with a mid-sized and well used CN rail yard. Across the GTA there are no less than half a dozen GO stations situated in the middle of vibrant, busy, and economically important industrial areas where converting land to residential use is likely not the right choice.

Satellite image showing the existing Oshawa GO station and its surroundings. While there may be some empty land, and a lot of surface parking, there is also the GM Assembly Plant and a litany of other industrial businesses. This, like several other parts of the GTA, is a key economic sector. Trying to turn these areas into residential TOD clusters is likely not an appropriate strategy. Image via Google Earth.

Then you have stations like Bloomington GO. Built next to the 404 and a major road, it sits in the middle of nowhere and its sole purpose is to be a park and ride station. Those kinds of stations still play a role in attracting GO riders in certain areas. With so many development opportunities across the GTA there is little reason to be suddenly turn that into another hotspot. It can simply sit there all on its own, and that is totally fine.

While there is some surface parking at Bloomington GO, the majority of it is contained within a gigantic parking garage, reducing the amount of land the commuter station uses. Perhaps many decades down the road development might happen around the station. But for now it is totally fine existing in isolation. Image via Concreteawards.ca

Far and away the most common type of development is what could be called ‘testing the waters’. These are stations like Brampton, Mount Pleasant, Port Credit, Clarkson or Aldershot in which they are surrounded by parking lots and low rise suburban development, but where only a handful of developments are taking place.

In some cases, such as Oakville, there are actually small little downtowns, often next to the waterfront, beyond the standard definition of walking distance (around 2km in this case) where development is gaining momentum. Oakville is already number 4 in terms of GTA GO station development. But its growing downtown will eventually start to push an urban corridor closer to the station. Once that happens, development around the station becomes much more desirable as it will seamlessly blend into the Oakville’s urban centre.

Often times it is the first developments that are the hardest. The idea of a condo surrounded by parking lots and next to a Canadian Tire and Walmart is hardly the most appealing, even if it is within walking distance of a GO station. But some people will be swayed by the initially lower prices for being the first to buy in, and once a few towers go up and start to establish something different, further development becomes a lot easier.

Not every station sits among a sea of parking. Some are in urban centres, though even among those there is some variety. There are the former village centres, like Brampton and Port Credit, who have become surrounded by growing and contiguous suburban sprawl, making them feel rather small compared to what surrounds them. Then you have cities like Hamilton, Guelph and Kitchener-Waterloo which sit seperated from their neighbourhoods by farms and forest, and whose downtowns are relatively vibrant places. One of the strengths these centres provide is that they provide an existing urban environment to build and expand on. Building an all new urban neighbourhood from scratch is hard. Modernizing a place that people already live in, shop in, work in, or go to school in, is a lot easier (at first at least).

It is probably no surprise that among the existing urban centres Hamilton, with a population of 569,353 according to the 2021 census, leads in current developments with 2262 units under construction or proposed around Hamilton GO Center, and 1750 around West Harbour station. From 2016 to 2021 11.7% of Hamilton’s growth actually took place in the downtown area. And that was taking place before GO established all day hourly service, and admit an aura of uncertainty surrounding the plans for an LRT line in the city.

A lot of the development simply builds off the existing urban landscape, filling up surface parking lots with residential buildings and what not. But one in particular, the Pier 8 development, is incredibly significant. In total it will only add 1500 residential units, which is small relative to most multi-block developments in the GTA. But it does so along the waterfront, and in an area that has never been a hub for this kind of building before. Along with being a place to live it will be a destination for Hamiltonians, and people across the GTA, as well as serving as a catalyst for extending urban re-development into new sectors of Hamilton’s central area. It also worth noting that Pier 8 is not about setting in motion the removal of industry from Hamilton's waterfront. As Hamilton’s general manager for planning & economic development Jason Thome mentioned in The Rocky Talky Podcast, the city’s long standing industries are a source of pride, and not going anywhere. The Hammer in all its industrial glory will live on.

The Pier 8 development in Hamilton will be a relatively small, but mighty, district for the city. Its the kind of urban incubator project that can help redefine an area and add to Hamilton’s existing urban landscape. Image via City of Hamilton.

While Hamilton may be todays shining star among GTA urban centres, it is unlikely to hold that title for long. Kitchener, which has 2582 residential units proposed or under construction (which is less than both of Hamilton’s centre stations combined, but more than each in a one-on-one battle), is setting the stage for something much larger. Kitchener-Waterloo (herein called K-dubs because that is a much cooler sounding name for it) will be discussed later. At the moment, it is time to move onto the last type of development pattern, the greenfield development.

The Orbit revisited

In part 1 of the GOing Urban series the Orbit, a massive planned community centred centred around a new Innisfil GO station, on a modernized Barrie line, was briefly mentioned. The idea of building entirely new towns or cities on land that is currently in agricultural use, or simply a natural landscape, and based around a rail station instead of a highway, is not a new idea. In the early 1900’s in North America the streetcar served as a catalyst for suburbs well outside a cities limits. And in Canada, particularly in the prairies, a mix of new rail lines and colonization resulted in hundreds of new towns popping up across the landscape in the late 1800’s and into the early 1900’s.

Once the mass adoption of cars and highway construction was underway, those sorts of development patterns faded away. Though investments in rapid transit have increased dramatically in the last few decades, they have almost exclusively focused on serving existing, urban and suburban areas of a city. Some, like Ottawa’s LRT, will have sections that travel through farmland on its way to one of 3 satellite suburbs. But in that case the land is part of the greenbelt and cannot be developed. Modern rapid transit had not really entered the hinterland beyond cities.

GO’s modernization will change that and could potentially revive that legacy of streetcar suburbs and railroad towns. Once the lines pass through the greenbelt, opportunities open up for the develop of all new towns and cities in conjunction with a rapid rail service that could run up to every 15 minutes. So far only one greenfield proposal exists, but it has started off the movement strong. The Orbit is a sizeable, development, 2.75 km in the north-south direction, and 1.5 - 1.7km in the east-west direction, and will ultimately be home to 150,000 people. It will eventually bleed into some of the existing suburban and exurban development in Innisfil, so in that sense it won’t create an entirely new city, but that is almost a trivial distinction given the scale of it.

Birds eye view of the plan for the Orbit. While it has to contend with existing development near the lakeshore, it still stands to create a community in which at least 40,000 of its residents will be within walking distance of the centrally located GO station. With proper, dedicated bike infrastructure, almost everyone in the Orbit could be within a 10 minute bike ride from the station. Image via Innisfil Accelerates

On 10 August 2021, the Ontario Government created a Ministerial Zoning Order (MZO) which establishes the legal framework needed for the developer to plan and build the community according to their planned densities and urban design. While this does not mean that construction is imminent, it does allow the developer to continue seeking private investments knowing they have the zoning needed. Additionally it allows for the GO station to be built, and other preparatory upgrades such as road or bridge expansions, as well as a new pumping station to service the community, which has already started.

As it stands the Orbit is unique within the GTA with no other comparable plans even on the drawing board at the moment. But no one has ever really attempted a from the ground up Transit Oriented Development on that scale before, in particular one in a greenfield. Whether this is a one off or a sign of things to come is very much unknown and will be a fascinating to watch.

And then one day a GO station appeared in our neighbourhood

While many people will be moving into a neighbourhood because they can walk to a GO train, others will find that GO has moved into their area. In some cases the number of people who can now walk to a GO station will be small owing to the highly suburban, low density nature of where a new station will be located.

Within Toronto however, many of the new stations associated with the SmartTrack project along with regular GO stations, are in vibrant, dense, often still growing neighbourhoods. In total, around 111,346 people will by 2031 find themselves a short walk away from GO, and in most cases that will mean one of the modernized, electrified lines with at least 15 minute service.

List of all the new stations under construction of being planned, and the number of people that currently live within walking distance of them (using 2021 census data). Chart by the author.

These relatively easy gains in ridership are just as important to the success of the new GO stations as all the upcoming developments are. They are the people who will create a customer base from day one and will help establish the kind of critical mass of people flowing in and out of stations that help make them safe. If you are not familiar with this idea, its is a variation of Jane Jacob’s eyes on the street. Her theory stated that a street lined with apartments and townhomes where people watching the street from their windows and balconies would acts as a safety mechanism for the neighbourhood. In transit stations it’s the same principle at play. An empty station can feel uncomfortable, unsafe, and for some people this could be a deterrent from using transit. But when a station constantly has people waiting, arriving, or people watching over from newsstands or coffee shops, those feelings of discomfort are greatly reduced.

Not everyone will be thrilled at the prospect of a new transit station. The reality is that new stations are going to create new demand for development, which is going to push up real estate prices in those neighbourhoods. This could lead to some people seeing rents increase beyond what they can afford, or simply being renovicted without even having the option of paying more for rent. It is easy to see how some people could see a new station as a threat, and those concerns should not be dismissed either.

What will the development landscape look like in 2040?

It is impossible to definitively say what the direction of urban growth in the GTA will be over the next two decades. There are any number of paths that cities could take and right now there are some pivotal issues and policies being debated which could radically affect that direction. Those debates, challenges, and the housing crisis in general are why there will be a part 3 of GOing urban as it is essential to understand the negative consequences that could arise from all the investments and developments.

However, there are strong indications that even with massive policy shifts, be it funding for co-operatives and affordable housing, or the elimination of exclusionary zoning, development around GO stations is going to continue at a record clip.

Hamilton has already been discussed as being a rising start among the urban centres of the GTA. But K-Dubs could very well match and eclipse what is being seen in the Hammer. Kitchener-Waterloo is one of the fastest growing cities in Canada. From 2016 to 2021, its population grew by 11.8%, to a total of 378,291 (the total population in the Kitchener-Waterloo-Cambridge metro area for 2021 was 571,000). Fueled by universities and a high tech sector, K-Dubs has the kind of money and drive to really develop in a much different way than a city its size would have in the past. They are the smallest city in Canada to have built a light rail system, and the region has consistently been pushing for improved GO train service for the past decade. There continues to be every indication that people, and money, are going to continue to flow into the city, and that urban development is very much a central strategy to its growth.

Milton is an equally strong indicator of the direction cities are taking. On 9 July 2020 they completed the Milton Mobility Hub Study which offers a vision of the kind of urban development that could take place around the GO station. The plan, which has moved onto the next phase of making it part of its official plan, would create an urban centre that could see 15,000 - 20,000 people within walking distance of the station.

Massing model of the kind of density being endorsed by the City of Milton around the GO station. This was being undertaken before the spector of a modernized Milton line was raised. Image via DTAH.

There is the High Tech Station Conos/Langstaff Gateway proposals that could see as many as 40,000 units in towers as high as 80 storeys, within walking distance of the Langstaff GO station in Richmond Hill. A proposal that came up as this was being written, by a consortium of developers and financiers could see as many as 5700 residential units built directly above the rail line in downtown Toronto. And there has been discussion of development near Bramalea GO that could be home to 12,500 residents.

While they are all still in the early stages, just those 4 development areas would represent an additional 62,000 residential units on top of the ones already outlined earlier.

And then there are the infamous GO parking lots. As of today very few have been developed. Mimico will see most of the surface parking developed by VanDyk Properties. And on 27 July 2021 Edenshaw purchased a 1.48 acre site in Port Credit from Metrolinx. But the overwhelming majority of the surface lots remain untouched at the moment. It is hard to get an exact number of how much development they could accommodate. But estimates range from 50,000 - 100,000 in terms of the number of residential units that could be built on the land currently used by the surface parking lots. That is an incredible amount of untapped potential, and while the slow pace of parking lot redevelopment may frustrate some, it’s also an opportunity that needs to be done right, something that will be addressed in part 3 of this series.

Finally, there is the question of additional GO projects that might be proposed and built that could increase the number of highly desirable development nodes. A modernized Milton line could allow for one or two more stations within Toronto, which would at a minimum capture an existing population base, along with any additional development it spurs. An extension to Bolton would open up new opportunities as well, as would a modernized Richmond Hill line that could add interchanges with the Eglinton Crosstown.

Towards the end of part 1 of this series it was stated that as many as 1 million additional people could be living within walking distance of a GO station between now and 2040. At the time that number probably seemed way out of the ballpark. But having laid out the scale of development that is being planned already it is clear that if that number is not achieved, it probably won’t be by much.

The constant feedback loop between increasingly modernized GO train infrastructure, and developments will play out in fascinating and unintended ways. Some of those outcomes are proving to be delightful and whimsical, such as the emergence of the urban GO station, which is a radical deviation from the suburban parking lots the agency spent most of its life cultivating. Not all of the outcomes will be positive though.

Two proposed developments, both incorporating GO stations into an urban setting. These are definitely not your parents GO train stations. Top image from Hariri Pontarini Architects via Urban Toronto and bottom image from Sweeney &Co Architects Inc via Urban Toronto.

Being in the vanguard of transit based development means being in the vanguard of the problems it creates

If, in the early 2000’s, you had read urbanism books or articles on Transit Oriented Development or New Urbanism there would have seemed to be no downside to this kind of development. Even a projected increase in real estate prices that would come with modern, rapid transit service was seen as a good thing.

But cities are complex and evolve in ways that are sometimes hard to predict. While Toronto and the GTA are seeing an explosion of development taking place around GO stations it is taking place amid a back drop of a serious housing crisis which has spilled beyond the borders of cities like Toronto and Vancouver and it is quickly moving across the country.

This is creating a situation where the modern, vital, rapid transit projects being built today are at risk of becoming directly accessible to all but a small, rather wealthy segment of the population that can afford the kind of housing that is being built, or the multi-million dollar 60’s bungalows that now sit within short distance of a new rapid transit station.

Part 3 addresses this complex interplay between the long overdue, and much needed modernized GO train infrastructure, the development boom it has ushered in, and the housing crisis that is affecting Toronto and the GTA.

If you want to find me on social media you can do so @Johnnyrenton.bsky.social on Bluesky. If you have any thoughts or feedback let me know in the comments.