The VIA High Frequency Rail project: $600 million and counting and still nothing to show for it.

How this project is fast becoming a once in a generation boondoggle and a scandal in the making

If by chance you are reading this and you have never had heard of the VIA High Frequency Rail project, that isn’t at all surprising. Between a general disinterest in public transport projects unless it’s something a person will use on a daily basis, the pandemic, and other critical issues such as the housing crisis, it’s understandable that it hasn’t got that much attention. But it should. Over its 8 year history it has gone from being a rather pragmatic, sensible project to one that has seen CDN600 million in public money sent to it. The result as of today? No construction of any kind has started, very few public documents have been published, and there is only the vaguest sense of what the vision for the project is today.

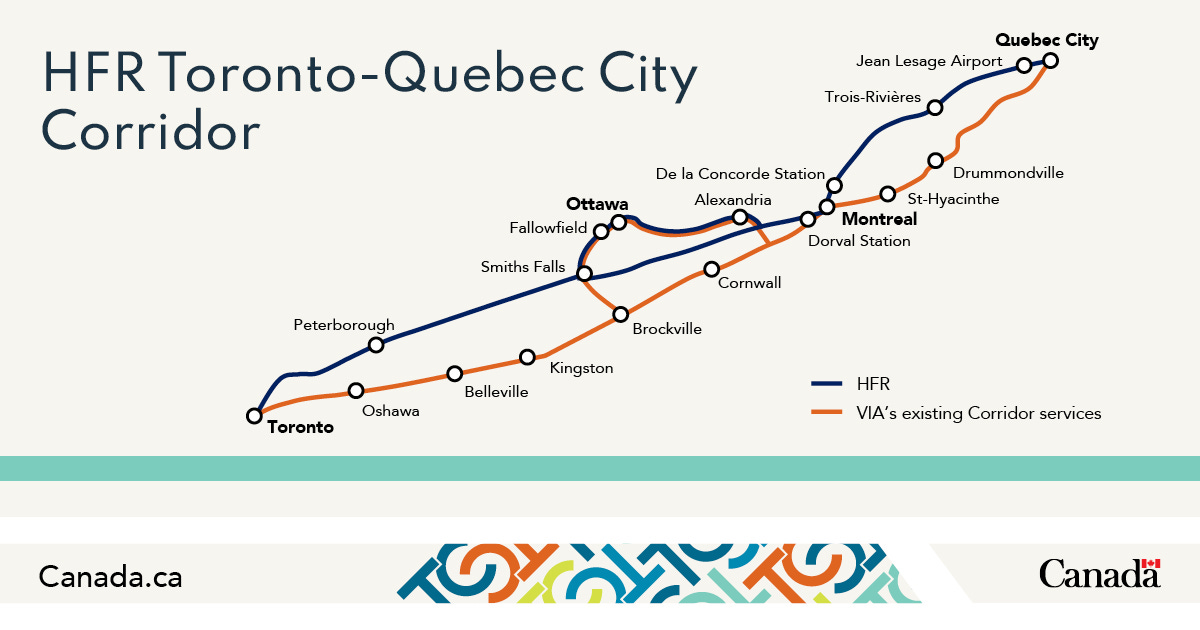

When the High Frequency Rail project was first publicly announced in 2015 it was a fairly low key idea. It wasn’t centred around trains screaming by at 300km/h. Instead it wanted to take advantage of long abandoned rail lines, or build its own track in lightly used corridors to begin the process of modernizing passenger rail in the Quebec-Windsor corridor. Its price tag would eventually stabilize at around CDN4 - 6 billion in 2017, which may have still have been a bit low, but likely not far from its actual cost. It wasn’t perfect. It didn’t actually address the issue of providing improved service on the fast growing Lakeshore corridor. But it did bring new service to places like Peterborough, Perth, and Trois-Rivieres. It would provide a much better route from Montreal to Quebec, and make a train trip worthwhile for residents of Laval. And by simply having dedicated track it could still clip along at 160km/h and actually be a reliable, and faster, service.

Initial reception of the project was largely one of indifference. Canada has seen many proposals for better passenger rail service in the Quebec-Windsor corridor since the early 1980’s. But most of them were completely unrealistic for various reasons and ended up collecting dust on archive shelves before going any further. Despite the HFR proposal being different in nature, and much more achievable, the cultural memory of past proposals never going anywhere mostly lead to shoulder shrugging and dismissal.

In 2019 there were signs that the project was progressing beyond board room visions and political platitudes. VIA received CDN71 million to conduct a detailed study into the feasibility of their HFR plan, an amount no previous study had ever received. And at the same time, as part of the their broader top to bottom rebranding campaign, VIA began to advertise the project online and in its stations. The video below, which somehow hasn’t been removed from their YouTube page, shows the vision that the VIA HFR proposal had evolved into.

I’ll save the details for another article, but what is important to know about VIA in the mid- to late-10’s is that they were doing something they had never really done before. They were being forward thinking, and proposing ideas that weren’t just bandaid solutions and working around the edges. There was an investment made for an all new fleet of trains for the Quebec-Windsor corridor to replace equipment that was up to 60 years old in some cases. They did a complete modernization of their brand and identity. VIA finally seemed interested in doing more than managing the status quo, and worked to get the public on-board with the idea.

An observer in 2019 could have looked at HFR and thought to themselves “this project has legs” because that was how it seemed at the time. But instead of it morphing into a more detailed version of the original vision, the project would begin to struggle and spiral into the money pit it has become today.

The first cracks start to emerge

There were some small warning signs early on that HFR was in trouble. The 2015 version of the project included stations in smaller towns such as Perth, Sharbot Lake, and Kaladar. This fit in with the VIA mandate of providing service to smaller communities, in addition to the major urban centres. But by 2019 they were gone, replaced with an asterisk indicating that other stations could still be considered. A minor change, but one that set the tone for the subsequent years.

To a certain degree the project had seemed to stall. Updates were few and far between and the media had all but stopped talking about it. There was no doubt the pandemic had caused priorities to rightly shift elsewhere. But even during that time urban transit projects still seemed to be moving along largely as intended. Then in April 2021 the federal government announced that Transport Canada would receive CAD4.4 million for risk assessment and mitigation, and CAD491.2 million would go to VIA Rail over 6 years, with almost CDN400 million of that being handed over in the first two years. This was followed up by an announcement in July 2021 by Transport Minister Omar Alghabra that the project would move forward into the procurement phase… eventually. That same month the minister toured Southwestern Ontario, stopping in London and Windsor to announce that studies would begin on the feasibility of HFR for cities and communities west of Toronto. On the surface it looked positive.

However those announcements also began to raise a number of critical questions. A map released showed an additional bypass route south of Ottawa, an aspect of the project that was completely new, barely discussed and had no price tag attached to it. They stated that they were working “with partner railways to negotiate dedicated routes in and out of city centres” but no more details or elaboration came on what that might look like, which is particularly critical in the case of Montreal. Then there were the early implications HFR could be a privatized service. The project was starting to feel different, but it lacked a focus and vision to really articulate what that difference was.

In March 2022 the procurement process officially began, with the launch of a new website to aid any companies who were interested in joining the project. But it also marked a radical change for the project, with Transport Canada officially taking over from VIA. The choice doesn’t seem to have been particularly amicable to VIA with CEO Cynthia Garneau, someone who had always championed HFR, unceremoniously leaving VIA Rail in May 2022. Whether it was the feds turning HFR into a pet project they could flaunt at election time, or VIA not being able to handle taking the project all the way to completion, is still not publicly known. But it was clear that this was a VIA project in name only now, and the agencies first real attempt at being bold had resulted in them their wings clipped and pushed to the sidelines.

From this point on the waters went from somewhat hazy to completely muddy. There were vague suggestions that the project could be more than was originally visioned. The transport minister publicly stated on a number of occasions that they were open to different ideas for the project, whether it was from companies looking to qualify for the bidding process, or municipal and federal politicians. There was the odd update, but nothing that gave insight or details into what the project will look like, or how the money was being spent. And the timeline for construction was getting pushed back further and further, with somewhere around 2027 being the earliest it might happen now, and even that projection is looking very optimistic now. The price tag, which was last publicly stated as being between CDN6 -12 billion, is now unknown. It might still be that price, but given the constantly changing vision and scope it may well end up being in the CDN15 - 20 billion range.

It would be easy to say that this is just how transit projects go. That they take time, and the bureaucratic wheels of government move slowly. You could also defend the project by saying that Canada has never actually had a modern, intercity passenger rail system, and planning and building one from scratch is going to take time. That there needs to be knowledge building, and a few mistakes made along the way. While both of those are true to a certain degree, the flaws and failings of HFR go much deeper than that.

HFR was simply an ‘okay’ project that only made sense because it was quick and cheap

When it comes to transit projects, whether it is a metro or intercity rail line, the two elements that most people will judge it on is how much does it cost, and how many people will use it and find it useful. And it goes without saying that as the number people who will directly benefit from a project increases, so too does the amount of money that can justifiably be spent on it.

When it comes to the original vision of HFR, it wasn’t a great project, it was simply okay. It would provide better service between Toronto and Ottawa, but it wouldn’t really do much between Toronto and Montreal. It also left the entirety of the Lakeshore corridor without any meaningful upgrades and would still force VIA between Toronto and Montreal to share tracks with freight trains and deal with the continually escalating problems that arrangement causes. While it might be easy to dismiss this corridor because it ‘already has service’ or because it doesn’t have cities as large as Ottawa or Montreal, that would be a mistake. From Pickering to Cornwall, the population of all the towns and cities on the Lakeshore corridor was 1 million in 2021, and are growing at a rate of 7.3% every 5 years, which is higher than the national average of 5% and is not far off cities such as Ottawa and Kitchener-Waterloo. There were other challenges as well, such as the less than ideal network it would have to traverse in and out of Montreal to get to Laval and beyond.

But the project was relatively cheap and wasn’t being billed as a full scale modernization of, or solution to, existing corridors. It was a way to increase and improve service between Toronto and Ottawa, Ottawa and Montreal, and Montreal and Quebec City, and serve some new destinations, without having to undertake a massive public works in the existing Lakeshore corridor, or invest too much in the mess that is Montreal (at least not right away). It also didn’t have the 15 - 20 year timeline a modernized Lakeshore corridor project almost certainly would.

HFR was about trade offs. And the proposition was that even though HFR was not the perfect, it was relatively quick and cheap, and still created some long term benefits.

With the price tag now almost certainly well above the CDN12 billion mark, that trade off is gone. Instead there is a less than ideal solution that is also getting really expensive, which is the worst of both worlds.

There is no reason why some work couldn’t have already started

One of the most anger inducing aspect of the HFR debacle is that no fucking work has been done. While the project would require creating all new corridors along a substantial part of its length, there are actually some sections which VIA currently owns and operates on. The track from Smiths Falls into Ottawa Station, and then onward to Coteau (which is at the very edge of the Montreal region) is going to be a critical part of any future VIA network. It is also single tracked, un-electrified, and has many at grade crossings that are in need of being upgraded to separate them from the increasing amount of traffic in Ottawa and the surrounding region, and allow for faster speeds.

The bar for what constitutes work is so, so, low. They wouldn’t even have to be building new track. Even something as simple as clearing trees to widen the right of way in preparation for an additional track would be better than nothing.

Instead progress on the one section of track they actually own right this moment is non-existent. Even from a political PR stand point this would have been such an easy section to do a bit of work and show the public that you are making some kind of real, tangible, progress, and wouldn’t require a huge amount to be spent either. It is really hard to think of a valid justification for why something isn’t being done in that part of the corridor.

A complete lack of transparency and accountability

The fastest way to create a scandal is by keeping secrets, and HFR is doing this quite well. Up until 2021 there wasn’t really anything that raised a ‘serious’ red flag. Having CDN71 million allocated to a feasibility study felt like standard practice and everything seemed to be going according to plan. But when that feasibility study was complete there were no public reports. Instead there was simply an announcement that HFR would receive a substantial amount of funding to continue the process.

To date the only major documents produced have been for the request for information (RFI) and request for qualifications (RFQ) processes. These are publicly available, but they don’t adequately detail what the vision of the project actually is, mostly because there is none. Those documents and information are also not tailored for the general public. They are for construction firms and contractors looking to get a piece of increasingly lucrative Canadian transit projects. An intrepid person could spend hours reading through them trying to gleam some semblance of what is going on, but few people are going to do that just to get a few paragraphs of the kind of information the general public would like to know about.

When it comes to showing what they got for their CDN71 million feasibility study, or where the current round of just over CDN500 million is going, it’s crickets.

For a project that has ballooned to ‘Canada's largest infrastructure project in generations’ it is irresponsible that so much money has already been spent and allocated towards it with so little to show for it, and no accountability.

The privatization question

As it stands right now VIA is currently a crown corporation, meaning that it operates independently of the federal government, but is still subject to government oversight and mandates. It’s goal is to be as close to profitable as it can be, but it is accepted that this isn’t always possible because it must provide some money losing services as a public good. This is also how transit agencies across Canada are structured, with the difference being that it is the province they are located in overseeing them.

The idea of privatizing VIA is not a new one. It was regularly discussed in the 90’s and 00’s, mostly as a measure to reduce the federal budget by getting it off their books, and sometimes as part of a larger ‘privatize everything’ ideology. In the US new passenger rail services are being built separate from Amtrak, with their key selling point being that they are going to be funded solely through the private sector (which so far has been not at all true), and be more efficient.

Privatization is something that has serious implications. Private operators cannot rely on yearly subsidies to cover operating loses. They need to make a profit. For private operators, such as Brightline in Florida, this means that local services are non-existent. They serve large centres, wealthy towns, or tourist destinations like Universal Studios, while smaller cities and towns, or even large cities that are not particularly well off, are left to pound sand.

If you are someone that lives in Ottawa and only cares about going to Montreal or Toronto, you probably dont care if it is privatized or not. But if you live elsewhere, such as Belleville or Smiths Falls or Alexandria, your view is going to be quite different since it is going to be your services that would be first on the chopping block.

It’s worth noting that when it comes to VIA Rail and intercity rail service in the Quebec-Windsor corridor, there are genuine discussions that should be taking place. In many ways VIA is an antiquated model and needs to be modernized for the kind of regional travel that trains now serve, versus the very different travel patterns of the mid-70’s when the agency was first established.

But that also gets to the heart of the problem when it comes to privatization and HFR which is that there is no discussion around it. The federal government has vaguely talked about working with private operators for HFR, and even floated the idea of private operators taking over the rest of the service in the Quebec-Windsor corridor. It constantly touts the role of the private sector in this project (as many transit projects in Canada do). But it fails to properly define what exactly private involvement looks like, something that could ultimately costs thousands of people their jobs, and maybe even service to smaller towns and cities. Even digging through very dense procurement documents dont really yield any clear answers, mostly because any option seems to be on the table right now.

The role of the private sector in transit projects has steadily increased over the past 2 decades. When the public-private partnership Canada Line opened in Vancouver in 2009 on time and on budget it was hailed as proof positive that the private sector was the way forward with transit projects. But since then there have been some pretty dramatic failures of this model such as the perpetually delayed Eglinton Crosstown, the Ontario Line who’s price almost doubled to more than CDN19 billion from the original estimates of CDN10.9billion, and the absolutely disastrous Confederation Line LRT project in Ottawa. With the role of the private sector in Canadian transit projects becoming increasingly problematic, and the over reliance on consulting firms instead of in house knowledge for planning and design, privatization and private sector involvement in the HFR project should be heavily scrutinized and publicly debated.

HFR has meant that opportunities that exist today are being missed

Prior to the pandemic, VIA Rail was on track to see 5 million passengers travel within the Quebec-Windsor corridor in 2020. That doesn’t sound particularly impressive, and in general it isn’t. But to put it within the context of Canada, that would have been the highest ridership levels for intercity service since the mid-1980’s, and perhaps even the late 70’s (the exact numbers are difficult to pin down).

In the first quarter of 2023, VIA Rail announced that it had moved 843,000 passenger in the Quebec-Windsor corridor. That means ridership is just a touch over 76% of what it was in the first quarter of 2019. However, VIA is still not running the same number of trains it was prior to the pandemic, with some routes only having around 70% of the frequency levels they did in 2019. By year end, when most of the frequency will be restored, it is likely they will be back to 2019 ridership levels. And with the exception of a small number of new trains between Ottawa and Montreal, these early results are being achieved with the same 40 year old plus equipment that they were using in 2019, on the same antiquated network. By 2025 there will be far more modern trains, a much higher seating capacity (reducing the number of sold out trains), a continually growing population, and at least the same frequency as there was in 2019. It is not unreasonable for VIA to hit 6 million passengers a year within the Quebec-Windsor corridor by the end of 2025, simply with the equipment upgrades that are already underway.

But there are many more opportunities out there which wouldn’t break the bank and would take anywhere from 2 - 5 years to make happen. Several stations, such as Kingston Station, are horribly inadequate for the passenger levels they see and haven’t seen a proper renovation in decades resulting in a poor passenger experience. There are the aforementioned corridors that they do own, stretching from Brockville to Ottawa and onward to the edge of the Montreal metro region, as well as a section of track from Chatham to Windsor. You wouldn’t even have to worry about electrifying the line right away since the new trains already have decent performance levels. Routes like London to Toronto, which are notorious for selling out, could have trains expanded to 8 cars or more to meet higher levels of demand.

By focusing on what can be done today, while still being done in a manner that puts any large investments towards dedicated infrastructure as opposed to giving CN free upgrades, ridership numbers could be pushed up a good clip. It is not unreasonable to think that with a sensible strategy, and given that ridership in the Quebec-Windsor corridor is already likely to hit 5 million in 2024, VIA could reach 7-8 million by 2030. Keep in mind that the projection for HFR is to hit 17 million by…. 2059. At the rate things are going for that project, VIA could be nearly half way to that target before a single shovel hits the ground if existing opportunities were seized upon.

That HFR ridership projection is also another example of some of the projects bullshit. Between population growth and having modernized, dedicated passenger rail lines, a ridership of 17 million 36 years from now is remarkably low. Either they are artificially deflating the number so that they can ‘beat’ projections, or they are really missing the mark on the actual ridership opportunities that exist in the corridor (to put it politely).

Throwing public money at the unknown

Right now, the CDN600 million that is being spent of HFR is being done purely in good faith (or a roll of the dice is you prefer that term). With no accountability, or transparency, or oversight, or even a clear cut vision, your guess is as good as anyone else’s in terms of what the outcome is going to be. To make matters worse this money isn’t even to study the entirety of the Quebec-Windsor corridor. Even more money will be needed for Southwestern Ontario, and the Lakeshore corridor and south shore route to Quebec when that time comes.

Maybe it will be great and come in at a reasonable price? Maybe it will be privatized? Maybe it will allow for some construction to begin in the next year, or maybe it will be 5 years before a single shovel enters the ground? Maybe it will be the original HFR vision but triple the price?

Nobody really knows. And after 8 years, with so much money already being spent, and so much more on the line, the lack of transparency and the arrogance of leaving the public in the dark is completely unacceptable.

So what should happen with HFR?

There should be an immediate halt to this project. At the very least they should have to show their work to the public before they continue so that people can decide whether they think the project, in whatever form they are deciding to go with, is worth spending public money on. Accountability and transparency is the bare minimum and if they can’t even do that then people should be losing their jobs and punted out of office as a result of it.

Beyond that, there probably needs to be a reset done not just on HFR, but on the idea of intercity rail in the Quebec-Windsor corridor, and other parts of Canada. That isn’t too suggest that there should be no investments because there absolutely should be. But Canadian cities have been transforming over the past 20 years, and that process is about to accelerate and intensify even more so over the next 20. Electric vehicles are no longer a dream and have the kind of momentum that means in the next decade they are going to become the majority of vehicles purchased, and maybe even on the road. That also means they will completely change the cost and economics of car travel. And there are regional passenger rail agencies like Metrolinx and Ontario Northland who are actually at the vanguard of passenger rail in Canada and making actual progress in providing more service.

All those factors, plus the need to discuss private sectors role in transit, and the relevance of VIA in contemporary Canada mean that planning for a modern intercity rail network doesn’t look the same as it did 10 years ago, let alone 47 years ago when VIA first began.

In its current form the HFR project will be a massive boondoggle, and quite possibly a scandal if the current government sticks around long enough. People need to begin calling out this project for the mess it is, and demand more accountability, transparency, and a result that will actually be useful and valuable.

If you want to find me on social media you can do so @Johnnyrenton.bsky.social on Bluesky. If you have any thoughts or feedback let me know in the comments.