The Ontario Northland Experiment

How an unlikely passenger rail project for Northern Ontario came to be, and why it calls almost all conventional thinking about trains in Canada into question.

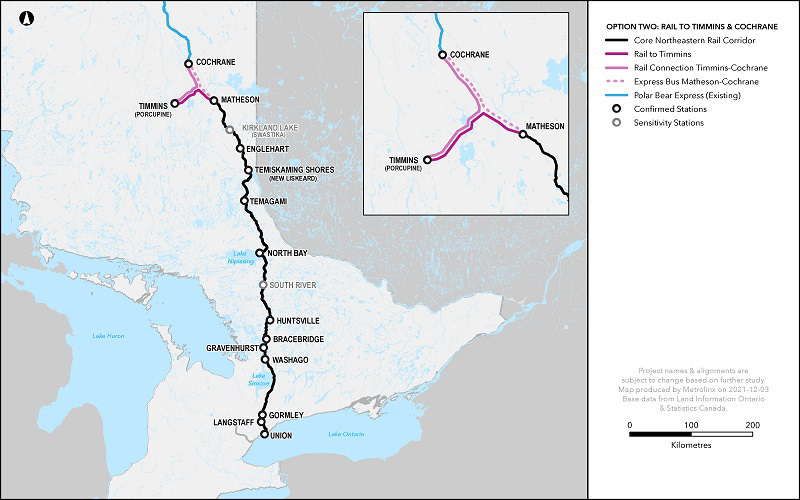

Canada is bad at trains. It is a sentiment that I have echoed before, and it still remains true. A recent project, the plans for Ontario Northland to reinstate passenger rail service from Toronto to Cochrane (and Timmins) proves this point, but not for the reasons one might assume. Of the litany of intercity rail projects that have been discussed or studied or moved into various stages of procurement over the past… 40 years… it is the one that was least likely to succeed, but yet it is the only one that did. It was the one that was least likely to be good, and yet it appears to be surprisingly decent.

How does a project that is actually succeeding prove the point that Canada is bad at trains? The short answer is because it did a lot of things other projects didn’t. And by being a project that is slowly starting to provide real data about the actual costs of creating modernized, intercity rail service into rural and northern parts of Canada it is already breaking long held conceptions about potential passenger rail opportunities in this country.

There is little doubt that this is going to be a massively influential project. And equally as important is that its influence won’t actually depend on whether it is successful in terms of ridership levels or decent cost recovery or any of those traditional metrics. What matters most is that the Toronto to Cochrance service will, in 4 years time, exist. That’s it. That is all this project needs to do to be the vanguard of a first wave of modern intercity rail investments in Canada.

So how did this project come to be?

A track once travelled

Up until 28 September 2012 there had been passenger rail service from Toronto to Cochrane, which also served the mid-sized northern hub of North Bay. The service was cancelled by the Ontario Liberal Party government being headed by Dalton McGuinty. It was a contentious decision at the time, one which was made in part because of the CAD400 per passenger subsidy that was required to keep it afloat.

But that wasn’t the only problem with the service. The equipment it was using was antiquated and far from modern (rubbish, trash or bollocks would be more accurate terms to describe them). Passenger cars were bought second hand from GO and had been built between 1967 and 1976 before the agency switched to its now infamous bi-level coaches. There were even spare passenger cars purchased solely for parts as that was the only way to keep them going. Buying second-hand equipment seems to have been a long tradition with Ontario Northland going back to at least at least the mid-70’s so it was part of the services identity long before the threat of being shuttered. While the interiors had been refurbished the experience would be akin to the current day one you get riding in one of the 70 year old VIA rail cars. The seats and curtains might be new but the rest of the interior feels like you have stepped into a time warp where people in formal dress could light up a cigarette and do some racism at any moment.

The condition of the rail stations at the time is harder to determine. Communities such as Kirkland Lake and Bracebridge currently do not have any old station buildings and may have used bus shelters or temporary structures when service was shuttered in 2012. Union Station, which was only 3 years into its massive modernization project, was still an absolute tragedy, aside from the Mmmuffins shop. And the remainder of the stations were, for the most part, rather typical early 1900’s rail stations. From the outside most looked okay, with Temagami being a particularly pretty station. Interior shots however are not easy to find so it is difficult to know what the passenger experience within the stations was like in the final days. I did find some people posting descriptions about their experiences. But they were all from train enthusiasts with heavily nostalgia tinged viewpoints so they didn’t really help understand what everyday passengers would have thought.

And then there was the travel time. A schedule from 2010 shows that the travel time from Cochrane to Toronto was 13h15, while travelling by car today would result in a trip of 7h30 (under ideal driving conditions). A trip from Toronto to North Bay was 5h40 by train and by car today would be 3h45 by car if toll roads were taken, and around 4h00 if they were not (again under ideal conditions). When serving northern communities like Cochrane travel time isn’t everything, especially in the winter when driving conditions can be treacherous, or even impossible if there are road closures (which does happen when there are major accidents on northern highways). But for cities like North Bay with a continuous freeway drive into the GTA total travel time matters a lot more.

In short, the service was rotting. While there were many articles from 2012 which discussed the operating cost, which was around CAD100 million per year for the entirety of ONTC which includes its passenger, freight, parcel, refurbishment and even hotel services, none mentioned what the cost of modernizing the service to attract more customers might be. It may well be that option was never given any kind of consideration. When governments began tightening their fiscal belts in the early 2010’s the Ontario Northland service was an easy target. But this wouldn’t last very long, and very little of ONTC in the end was actually abandoned.

A Populist makes an announcement from a basement

When Doug Ford announced he was running for the Ontario PC leadership spot on 29 January 2018 it was largely mocked (often by smart people who I like a lot but also should have known better). His announcement took place in his mom’s basement and it was less than 2 years after his brother Rob’s infamous tenure as the mayor of Toronto came to an end, which many though would cast a shadow on the Ford name.

But Doug Ford ran a populist campaign with a focus on Northern Ontario that the other parties lacked. Given the importance that the north is set to play in the coming EV revolution it now seems obvious why paying attention to, and investing in, that region of Ontario matters. One of the most discussed parts of his 2018 election platform within Northern Ontario was his plan to reinstate rail service from Toronto to Cochrane, and invest in Ontario Northland overall. This proved especially popular with communities and cities still bitter about losing the service, and in other parts of the north where bus service was degrading yearly as private operators bailed on the less profitable northern routes.

In the initial announcement about the plan to reinstate rail service the cost was pegged at CAD45 million for refurbishment and operating costs. This was never realistic in the slightest. But few people seem to have questioned that number. Northern communities wanted their service back, train advocates wanted more trains and simply went along with it, and the rest of the population simply didn’t care enough or even know this was a thing.

Ford would of course be elected and several years passed by with little to no mention of the promised service. Northern communities were not going to forget it though and maintained pressure on the government.

Then in March 2021 the Ford government announced that they would budget CAD5 million to perform a proper study into the Toronto to Cochrane service. It wasn’t much given that Canadian transit agencies serve up studies like Dairy Queen serves up ice cream. But it was a start. Just over a year later in April 2022 CAD75 million was announced to fund the reinstatement of the rail service from Toronto to Cochrane.

Even though the price tag for the project had risen 67% it was still too low. At best it would cover the cost of buying new, modern trains, and that was about it. In an article I wrote in July 2022 I stated that the cost would rise even more from the CAD75 million price tag, and that no one would care.

That is exactly what happened. On 15 December 2022 the Ford government announced that brand new trains had been purchased for the service. These would be the same ones that VIA Rail ordered at the end of 2018, and have actually started using on the Montreal to Ottawa service, with other parts of the corridor to see them in the coming years as more trains are delivered. And within that announcement came the not-at-all surprising news that the project cost had been revised to CAD139.5 million. Triple the original estimate, and nearly double the second estimate. While it is approaching the holiday season and people are busier than usual, people always seem to find time for rage and there seems to be little, if any, negative media or political reaction to the increased cost of the project.

While this new price tag is more realistic, it is unlikely to be the last time there is an increase in the cost of this project.

Canadians finally get to see the real cost of rural and northern intercity rail service

One of the most interesting parts of the Toronto to Cochrane service is that real costs for modern day, longer distance, intercity/inter-community rail are finally going to be laid bare. While it won’t be applicable in every situation, it will actually provide some data that isn’t just theoretical.

In examining the costs of the project the easiest place to start is with the trains themselves. Based on VIA’s order of 32 trains at CAD989 million (for a set that has 5 passenger cars) you come up with a cost of CAD30.9 million per train. The Ontario Northland train will only have 3 passenger cars, but it still has a big diesel locomotive (when EXO ordered 10 new Siemens Charger locomotives in January 2022 the total cost for the lot of them was CAD132 million). That likely puts the cost of Ontario Northland’s new trains at CAD24-25 million each, or CAD72-75 million in total for the project.

Then there are the costs associated with modernizing stations. Calculating this is challenging because it requires looking at the needs of each station. Three of the 16 stations within Toronto/the GTA…Union, Langstaff and Gormley, should need very little done to them since Ontario Northland can use GO’s existing facilities. The only wildcard is the inclusion of a business class car, something that Ontario Northland did not do in the past. VIA makes its lounges part of a business class ticket, and whether Ontario Northland does the same is unknown. If they do, and they cannot simply use VIA’s lounge at Union, then there will be an additional cost to add to the list. North Bay and Cochrane should require relatively minimal work since the former is still in use as a bus station, and the latter an active train station as the start of the Polar Bear Express rail service. Stops such as Kirkland Lake, Porcupine (Timmins) and Bracebridge will need some sort of station facilities built since none of those locations even have an old one to renovate.

Even if a station building still exists it might not be as simple and cheap as it first appears. In Gravenhurst the old station is still around and is in nice shape. But it is now occupied by a small rail museum, coffee shop and veterinary services. Accommodating passenger facilities will either mean kicking out existing tenants and renovating (if it is even suitable for modern day passenger volumes), or perhaps building an entirely new structure adjacent to it. A station like Temagami may have higher costs associated with reinstating passenger usage due to the extra value the community puts on its historic nature.

There are plenty of recent, real life examples that can offer a guide as to how much station renovations or construction are likely to cost. Something as simple as the VIA stop in Smith Falls that opened in 2011 came in at a cost of CAD750,000, or it could be a bit larger, like Fallowfield Station in Ottawa, which comes in at around CAD 2 million in 2022 dollars. When Windsor Ontario had a new station built that was about 2 or 3 times the size of Fallowfield it came in at CAD6.3 million in 2012 dollars. In 2015 CAD1 million was spent to do some restoration on Brockville VIA Rail station primarily to the exterior. And in 2016 VIA Rail spent CAD2 million on Kingston Station in order to upgrade HVAC systems, do roof repairs, and other basic work to keep the station from falling into disrepair (which was just barely over a decade after the last renovation project done in the early 2000’s).

Even if the 3 Toronto stations, plus Cochrane and North Bay require zero dollars to accommodate Ontario Northland service, the remaining 11 stops will absolutely need varying degrees on investment to modernize or build them. A conservative cost would be around CAD20-25 million but having it approach CAD30 million is not out of the question.

Just the stations and the trains put the cost of the project between CAD92-105 million, leaving somewhere between CAD34.5-47.5 million for any work needing to be done to the infrastructure itself, that being the track, crossings, signals, etc. This is the biggest wildcard factor in the project.

From Union Station to Washago (just north of Lake Simcoe) the service will start its travel on a line owned by Metrolinx, and then enter a line owned by CN. Because the first section of CN line is part of its transcontinental route and is a heavily used line the track should be in reasonably good condition.

While adding a couple passenger trains a day may not seem like a lot, freight lines rarely have much excess capacity. They add track only when it’s absolutely needed, and will remove track if freight volumes do not justify it. The impact of even a couple more trains a day on lean running freight lines could necessitate constructing more sidings to ensure the travel times the Toronto to Cochrane project will need.

From Washago to North Bay the Ontario Northland trains will still use a CN line, but a lesser used and lesser maintained one. Even a quick tour on Google Maps and Streetview make it clear that this is a second rate line. When a crossing does have a signal system, it is almost always just lights, lacking the protective gate. And even the lower quality Streetview images allow someone to easily identify rotting railway ties which seem to be a common site along the line.

The section from North Bay to Cochrane is owned by ONTC and sees even less use. It’s condition is also worse than the section leading into North Bay with rails being bolted together (this is the kind of track that creates the “clicking clack” sound of “golden age” trains) and which also have a tendency to be harder on equipment. When the City of Ottawa launched its Carelton University shuttle (aka the O-Train pilot project) in 2001 it did so as cheaply as possible and launched service on track that was bolted together. But between wheel wear and ride quality it was quickly realized that the track was not suitable and needed to be converted to welded rail. Rotting ties are also a common sight when using Streetview, as are crossings with no gates, and in some cases no lights either.

The reason all this matters is speed. Whether it is geometry of the line, track condition, or Transport Canada regulations, a lot influences just how fast a train can go. And for passenger rail service speed matters if it wants to, at a minimum, be competitive with car or bus travel.

This doesn’t mean a service has to be able to blast along at 200 or 300km/h. But operating at 60km/h isn’t going to make it competitive if drivers can book it at 80, 100 or in some cases 110km/h. In the case of the Ontario Northland service, reasonable speeds on the section from Washago to North Bay is going to be critical in terms of making the service attractive to residents or holidaymakers heading to or from Toronto to Gravenhurst, Bracebridge, Huntsville and North Bay itself. The nature of northern living means that the train can probably operate at somewhat lower speeds beyond North Bay and still be reasonably attractive. But even then that section is going to require work to bring it up to that standard.

How much it costs in the end still remains to be seen. But it would not at all be surprising if that component of the project ended up costing closer to CAD100 million when it is all said and done.

So, at this point what you have is a project that will likely approach CAD200 million when completed, and would cost even more if it wasn’t able to take advantage of Metrolinx’s massive station and infrastructure investments in Toronto and the GTA. All that for a service that might, even by the governments most generous estimates, only increase its 2012 ridership numbers by 60%, to 60,000 passengers per year by 2041.

When viewed through that lens it seems like kind of a crazy investment, at least relative to what Canadians are used to spending on longer distance, intercity rail (which is essentially zero). But that is what it costs in order to bring modernized service into existence. However, it does bring up the critical question of why has the Ford government been so willing to bring this project forward and be the first to market with this kind of service? You can understand why they support urban public transport because they are the party of developers and urban public transport is cocaine for that industry. But what is the raison d’être for the Toronto to Cochrane project?

The path of least resistance

One could try to justify picking the Toronto to Cochrane project as being “the” Northern Ontario project by claiming it has the lowest cost among all possible options, such as reinstating service west of White River, developing an Ottawa to North Bay, Sudbury an even Sault Ste Marie, or a service from Toronto to Sudbury. Someone could say that having it serve 3 major cottage country destinations makes its potential ridership the highest of the bunch. It would even be possible to link its importance with the Ring of Fire mining project in Northern Ontario, giving the Ontario Northland service the same degree of secondary economic benefits that urban public transport projects do.

In reality, the Toronto to Cochrane service was probably proposed because it was a line that had existed not that long ago (it had only been shuttered for 6 years when it was first proposed). And it was likely assumed it could be done on the cheap while scoring political points with the various provincial ridings it would serve. It was an easy idea to toss out on the campaign trail.

This leads to the next question which is why did it manage to happen? Again, it isn’t actually that complicated. It was popular with voters in the north, and people in Southern Ontario just didn’t care about it, Most probably didn’t even know it existed (a large part of the population probably still has no idea because why would you when it is not going to be relevant to your life). From the standpoint of a political party it is actually pretty easy to move forward with its ambitions even if there is not a ton of overall support so long as there are high levels of disinterest from the public, and very little opposition.

Perhaps the one question which doesn’t have an immediately simple answer is why has the project actually seemed to do things right in terms of buying new, modern trains, and actually putting meaningful amounts of money into it. Maybe the government feels pressured to maintain support in the north and just needs to get it done at any cost. It could just be they are doing the math and have come up with a result that shows higher initial capital spending will result in a more popular, and lower subsidy service over the long run. But in Ontario Northland’s updated initial business proposal for the project, they actually show that there would be zero difference in ridership levels if modern equipment was used versus second hand trains and passenger cars. This finding seems… surprising.

It would be valuable to understand how this project managed to become good, but that kind of insight is going to take a fair bit of research, or just time (future interviews with outgoing Ontario Northland CEO Corrine Moore once she leaves the agency might be the first opportunity to gain more details on the inner workings of the project). But really, as long as the project is done right in the end, why that managed to happen is probably not going to be relevant to most people. Sometimes shit just happens, you get lucky, and there isn’t much point dwelling on why.

How can this project fail, yet still be successful and influential?

There are numerous ways you can judge the success of a project. You could look at what the subsidy levels are, how many passenger kms the service generates (ie the total distance covered when adding up the length of each passengers trip), revenue, on time reliability, etc. All of those metrics provide great data points for those who need to understand it in detail. For the public at large and the media, the simplest metric (and one of the most important ones) is what is the ridership.

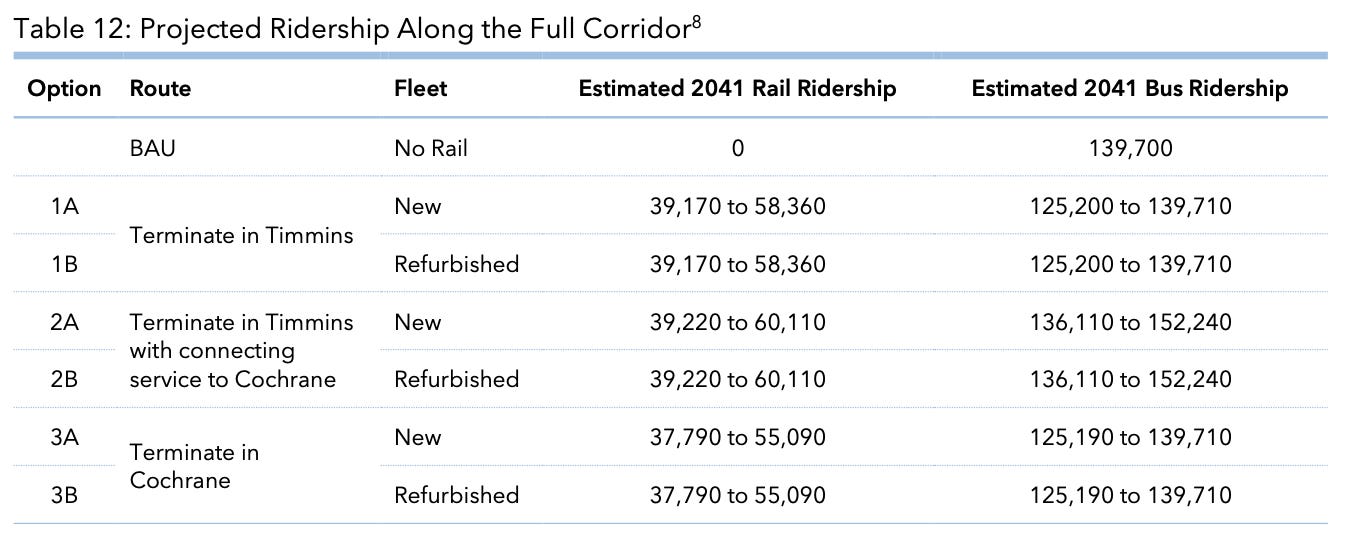

In 2011-12, its last full fiscal year of operation, the Ontario Northland line from Toronto to Timmins saw around 40,000 passengers. A bare minimum for the project not to be a complete failure would be for ridership to at least equal that. According to the agencies updated initial business case, ridership projections for 2041 for the plan chosen to move forward on are between 39,200 and 60,110. It would be surprising if the line failed to achieve even the lowest ridership projection.

Another valuable metric is understanding how much needs to be spent covering the gap between revenue and the total operating budget. The operating subsidies for the reinstated service have been targeted at CAD11.8 - 12.6 million by 2041 so there is a clear goal in mind for what will be considered an acceptable subsidy level. If ridership numbers only ever hit the 2012 level of 40,000 passengers per year that would work out to a subsidy of CAD295 - 315 per passenger. If they managed to hit 60,000 by 2041, that would put that number at around CAD197 - 210 per passenger. Still high but that would be roughly 50% lower than the services past iteration which would be a solid improvement.

In theory, even with the modest gains projected over the projects 2012 variant, it should be successful, to some degree or another. But it also doesn’t matter. The project simply existing is the only thing it needs to do in order to be a game changer for Canada. How?

Well the first reason is that it will be an actual, real life, functioning example of what longer distance, rural and northern intercity passenger rail can be like when it is built to modern 2022 standards. It will be something you can see, touch, and even ride. Yes there are other trains elsewhere in the world, but lots of people can’t afford to travel those kinds of distances, and it just hits different when it is in your own country, and it’s serving Canada’s geography. And the fact that it is the first semi-major investment in that kind of longer distance, northern, passenger rail service since at least the 1970’s, and by some measures since the 50’s and 60’s, is going to be notable and attract attention.

The way it came into being is also incredibly important. This wasn’t a federal project, nor did it have any federal involvement, including its funding. It has been fully guided by a provincial government. This is in contrast to the federally run VIA HFR project (which is larger in scale) where at year 7 of its existence it has earned to the right to be called a failure. Given that many potential projects are all inner provincial in nature, and the Feds poor track record, it makes sense that the provinces should try their hand at leading them.

Some small indications that this trend could take hold are out there. The new far-right premier Danielle Smith came out in a letter to Calgary mayor Jyoti Gondek saying that she wants the city to work with the province and private sector to build a train from Calgary to Banff, including to towns along the way such as Canmore (the YYC-Calgary-Banff rail link is a particularly interesting tale for another time). But as has been the case with Alberta, support for intercity services seems to almost exclusively rely on the private sector building and operating it without any public funds.

Then there is the work being done to bring the rail line to Gaspe up to a higher standard so that it can, at first, be used for more efficient freight train movements and then eventually passenger service is being headed by the Government of Quebec. Though at this point there is no formal, or even informal plan for passenger rail on the line…it is more of a wishlist item at the moment. The most recent study into the cost of restoring service on Vancouver Island was an initiative by the Government of BC, even if they did nothing afterwards. So the momentum towards more provincial involvement is already starting to emerge, even if it is still in the early stages of the movement. The Ontario Northland project should help accelerate that trend.

Being influential doesn’t always mean bringing about results that are rainbows and unicorns. The Ontario Northland project does also provide a reality check. Most obviously is going to be the cost. With a price tag that is likely to approach CAD200 million it is going to dash a lot of peoples dreams. The idea that reinstating passenger rail service can be done be done on the cheap is slowly being put to rest. Especially when you consider no other project outside the GTA would be able to do it at this cost.

For anyone who takes even a slight deep dive into the Toronto to Cochrane service, they are going to realize that it would have been even more expensive had Ontario Northland not been able to take advantage of GO’s infrastructure through its partnership with Metrolinx. They get two suburban stations, a radically modernized Union Station, and good quality track in and out of the GTA, right out of the gate. An exact estimate is hard to develop, but if the Ontario Northland had to recreate the conditions it gets through Metrolinx themselves (and not even at the full scale GO has done them) it would probably add another CAD50-100 million to the project, and even then that number is probably too low.

The reason all this can happen is that Ontario is spending an incredible amount of money (somewhere in the neighbourhood of CAD20-23 billion over a period of a decade), in order to fully upgrade and modernize the heart of the GO train network. This is in addition to other key projects such as completely overhauling Union Station and completely changing the passenger experience within it. While the majority of the GO modernization project is still under, or is just starting construction, they are creating the perfect conditions for a core regional rail system that will allow for future lines to simply be “plugged into the network”.

Having those conditions already in place, along with the system itself being increasingly integrated with local transit options, makes projects like the Ontario Northland one, or even potential future extension of GO train service into Caledon much easier, cheaper, and more attractive. When it comes to longer distance intercity services to regions that would ultimately feed into Vancouver, Calgary, even Montreal or Halifax, it is going to force some people in those regions to evaluate whether regional rail investments need to come first. It will throw cold water on some plans, but that isn’t a bad thing in the long run.

There is one final impact this Ontario Northland project is having that is worth discussing. And it centres around how it calls into question long held orthodoxies and conventions surrounding passenger rail in Canada (that for one reason or another have never really been challenged).

Can a northern passenger rail service be better value for money than an intercity line?

One long held assumption by most people who are interested in, or pay attention to, passenger rail in Canada is that outside of the Quebec-Windsor corridor the region with the highest potential is Calgary to Edmonton. It has the 4th and 5th largest cities in Canada (or the 4th and 6th depending on how exactly you measure it) and it is separated by 300km which in terms of Canada’s geography is relatively short. All the magical ingredients are there for success (or so the story goes). So in theory it should be a more successful project to undertake than a rail line into Northern Ontario.

Or would it be…

Let’s say that a plan was put in place to develop a rather simple intercity service between the two Alberta cities (along with a stop in Red Deer and some stations in smaller communities along the way). It wouldn’t be fancy, and pretty much be akin to VIA’s current service in the Quebec-Windsor corridor meaning trains top out at 177km/h (or around 160km/h in practice) and giving travel times by train just a touch faster than driving under ideal conditions. Such a project would require all the farm crossings to have protected gates and signals installed (of which there are several hundred along the line), stations would have to be reactivated and renovated or built, track rebuilt to allow for those top speeds, more of the Siemens trains ordered, etc. Even if you don’t bother serving Edmonton’s downtown (that would require building a new, rather costly, line into the urban heart of the city) and just have a station in the south end, the lowest possible estimate would put that price tag around CAD3.5 billion (in reality it would probably be in the CAD4 - 5 billion range but low balling still illustrates the point).

In order for a line between the two Alberta cities to get the same value for money (when you compare capital costs to build the project versus ridership) as a Toronto to Cochrane service that cost CAD200 million and had ridership levels of 40,000 passengers, the Calgary to Edmonton service at CAD3.5 billion would have to move 700,000 people. If the Ontario Northland service had a ridership of 60,000 people per year, the Calgary to Edmonton service would need 1.05 million passengers. If the cost of the Alberta line increased, or the Ontario Northland project’s cost comes in close to its current budget, then the passenger levels needed to maintain the same value for money get even higher. But a million passengers should be an easy achievement for this golden child corridor, right?

Here is the problem. In 1982, just a few years before the service was shuttered, VIA Rail moved just 53,000 passengers between Calgary and Edmonton with Edmonton, Calgary and Red Deer having a combined population of 1.17 million people at the time. And that was the highest it had been since 1969. Since then the population of those 3 cities has roughly doubled so clearly that would have an impact on the potential customer base today. But lets take a look at the Quebec-Windsor corridor. There the population grew by around 55% (5.7 million people) over the same period. Most VIA service has remained, and in some cases dramatically increased for cities like Ottawa. Yet, the ridership levels for passenger rail (including ridership for GO trains where it duplicated or effectively replaced VIA service) only returned to early 1980’s levels sometime around 2018 or 2019.

If you consider historical data, and the trends the continually active Quebec-Windsor corridor saw, it is not unreasonable to question just what exactly the ridership levels would really be on a Calgary to Edmonton service given what they were in 1982. And once you develop a cost for the project that includes bringing service back to downtown Edmonton (which is necessary to develop a properly attractive service) you start to wonder whether a line from Calgary to Edmonton could have the same value for money as the Toronto to Cochrane line.

The idea that a passenger rail service to Northern Ontario could “outperform” (based on capital cost to develop the project versus ridership) a service between Calgary and Edmonton runs counter to almost everything that was said about longer distance, intercity services in Canada over the past 4 decades. And it is the very existence of the Ontario Northland project, and the slow emergence of real data and numbers, that is allowing these kinds of questions to be asked.

The reason why a Toronto to Cochrane service would perform so well is rather logical, and it boils down to Toronto itself being so big, and having such a strong economic and social pull on surrounding regions that it can even attract people as far away as Northern Ontario. Even along the entire length of the Quebec-Windsor corridor 62% of all trips involve leaving from, or heading to, Toronto. It is also not the only project that is flipping conventions on their head. The only passenger rail project in Alberta that has gained any kind of traction in at least 4 decades is a proposed line from YYC to Calgary to Banff. However in this case it is Banff and the surrounding national parks, not the much larger city, that is the driving force behind it.

Does this mean that projects such as a line between Calgary and Edmonton are not worth pursuing? Not at all. While it might seem like I am dunking on the line between the two major Alberta cities, there is still value in building it even if its actual potential and value for money is possibly lower than what it has been made out to be.

And in fact the Ontario Northland project is going to give agencies, governments, and interested parties all across Canada exactly the data they need to show why their project is “the most important”, no matter what the outcome of it is.

It’s all just vibes and facts and numbers can mean whatever you want

Just as I was able to make an argument that the project into Northern Ontario could actually be better value for money than even a low cost Calgary to Edmonton service, someone in Alberta could easily use the Ontario Northland project to make the exact opposite argument. If they measured the results based on revenue, or passenger kms travelled then maybe the scales would tip back in favour of Calgary to Edmonton being the better investment. People could just continue to ignore the historical data and base ridership projections on… *waves hand*… other factors that yield much better results. It could be claimed that it is all about the speed and if a service that might, at best, average 75km/h and barely get above the 100km/h mark then one where speeds can hit 160 or 170km/h is going to be much more desirable and successful. Or the fact that a Calgary to Edmonton line will ultimately require less per passenger subsidies than the Toronto to Cochrane project could be used as another proof for their case.

It is very easy to manipulate and interpret data in a way that gives you the answer you want. And no matter what the outcome the Ontario Northland project is going to give people data that they can use to their own advantage.

That makes it seem as though everyone who proposes intercity rail projects is just going to lie and talk whatever nonsense they need to in order to sell their idea. Some definitely will and there is a small chance they could be successful. Others might take it to an extreme level, like is being done with the Hyperloop proposal in Alberta, and be laughed at like the charlatans they are. But there will definitely be some people involved who genuinely look at all the data openly, try to understand all the pre-existing conditions on the Ontario Northland project, the actual cost, and use that information to make a better plan. And ultimately agencies or politicians will need to have a good, realistic plan to actually sell in the first place.

In the end though, as extremely online people would say, a lot of it just boils down to vibes. The Toronto to Cochrane service is happening because a populist premier realized it would be very popular among the northern communities it served and rolled with it. No altruism, no real hidden motives, just a classic, almost old-timey, opportunity to secure some seats in an election and savvy politicking. The reason it has become a good project that will use new, modern, train sets is because the social climate and current expectations of Ontarian’s, the groundwork of which began being laid in the early 2000’s, seems to have allowed it to happen with very little friction (regardless of why that decision was made in the first place).

And the reason why people in other parts of Canada are going to start paying attention to this project is because its cool and exciting. It’s a modern train, that will serve reasonably modernized, often very pretty stations, in beautiful parts of Canada that haven’t seen any kind of attention or meaningful investment in passenger rail in half a century. And it went from campaign promise to purchasing new trains in 4 1/2 years. How fucking great is that?

Projects like HFR have become an utter mess because they over complicate things and fail to garner public interest. What started out as a way to relatively straightforward, kind of clever way, to increase service, speed and reliability in the Quebec-Windsor corridor has been a disaster. Now it is about privatization, maybe high speed rail or maybe not, the idea that it would actually serve smaller communities on the way seems to have been binned, and so on and so on. The fact that there seem to be just as many articles and posts written about the Ontario Northland service as there has been HFR, despite serving a fraction of the population, points to how much more engaged the public has been with the northern project.

But the Toronto to Cochrane service, along with the GO modernization project, largely avoid all of HFR’s nonsense. At their essence it’s about modern train service that serves communities (turns out people like trains that actually stop in their neighbourhoods, towns or cities). It is going to cost what it cost in order to achieve that goal and it’s going to be really cool. That’s it. Good plans with good vibes.

There is a larger, more academic, conversation to be had about the nature of modern intercity passenger rail service in Canada and long held assumptions and orthodoxies that make no sense in 2022. A lot of bad ideas need to crushed. Even then, a Tik Tok’r getting hype taking a shiny new train to Cochrane, and probably seeing Northern Ontario for the first time, is almost certainly going to do more to advance modern day thinking about passenger rail in Canada than anyone else. And I am totally here for it because the kids these days are alright.

The Ontario Northland project shouldn’t have been successful. It seemed little more than a flippant, easy to break, campaign promise. But it has been because it managed to avoid falling into the traps other intercity proposals do, was able to take advantage of Metrolinx investments, and hasn’t treated northerners as second class citizens only worthy of a second class service. That will be its legacy, regardless of whether standard metrics dub it a success, and why it will be in the vanguard for intercity passenger rail in Canada for at least the next decade or two.

Authors Note:

I will avoid a separate post to say that this site is now back after a hiatus. There will be more to come in the new year along with some changes to topics discussed, writing style, and overall tone of many of the articles. And going forward, as some people may have picked up in the article, there is going to be more of a focus (in the short term) on breaking down and questioning a lot of the assumptions and orthodoxies surrounding passenger rail in Canada. Eventually I will return to social media, once I find a platform I enjoy (I know many people have gone to Mastadon but man, what a pretentious place that is). But for now being away from it is quite refreshing and for anyone who isn’t I would suggest giving it a try. And lastly, solidarity with all the rail workers in the US who are fighting for reasonable working conditions.

If you want to find me on social media you can do so @Johnnyrenton.bsky.social on Bluesky. If you have any thoughts or feedback let me know in the comments.

I'd like to propose a different comparison for why this line makes sense over others. Regardless of cost, driving long distances in Northern Ontario is recognised as a dangerous and unpleasant activity by residents. Thus, the railroad is seen as a lifeline regardless of the state of roadways, to be compared with the cost of 4-laneing the highways.

Against this, most lines in other provinces don't compare. I would suggest only two with existing poor road connections that might:

- The Kettle Valley route, which unfortunately was even more prone to disruptions than the current highways, and would effectively require the originally proposed long tunnel under Tulameen Mountain to be built. $$$$$

- Saguenay.