The Dutch High Speed Rail Debacle

How the first Dutch high speed rail line failed to meet its original vision 14 years after launching its first services, and what North America can learn from it.

In North America jealously of high speed rail systems often cloud our view of them. They seem to be perfect. A no brainer. So obvious that there is no way they can ever fail. Of course that is bullshit. Spain’s high speed rail has been a hot bed of political and corporate corruption. In France there are growing questions as to whether the ban on 3 hour or shorter domestic flights is not about climate change but instead a way to artificially build up what had been a relatively flat TGV ridership. And then there is the master class in disasters that is the California high speed rail project.

One project that flies under the radar, but is as instructive as any of the other failures, is the case of the Dutch high speed rail project.

It is a saga that starts in the post Berlin Wall, rise of the new EU 1990’s, era when much of Western Europe was starting to re-emerge on the global stage in a big way. It would not only incur cost overruns and delays, but would be part of the reason a train manufacturer was forced to merge or go bankrupt, put a consortium on the brink of bankruptcy for years until that end was unavoidable, would cause political resignations, public backlash and force the country to rethink its passenger rail priorities.

Nineteen years after service was supposed to start, seventeen years after the line opened for testing, and fourteen years after the first public trains began running on HSL-Zuid, domestic high speed service still doesn’t exist in The Netherlands. And even when it does finally happen, it will still fail to meet the original vision set out in the halcyon days of the 1990’s.

Anything was possible in the new European Union

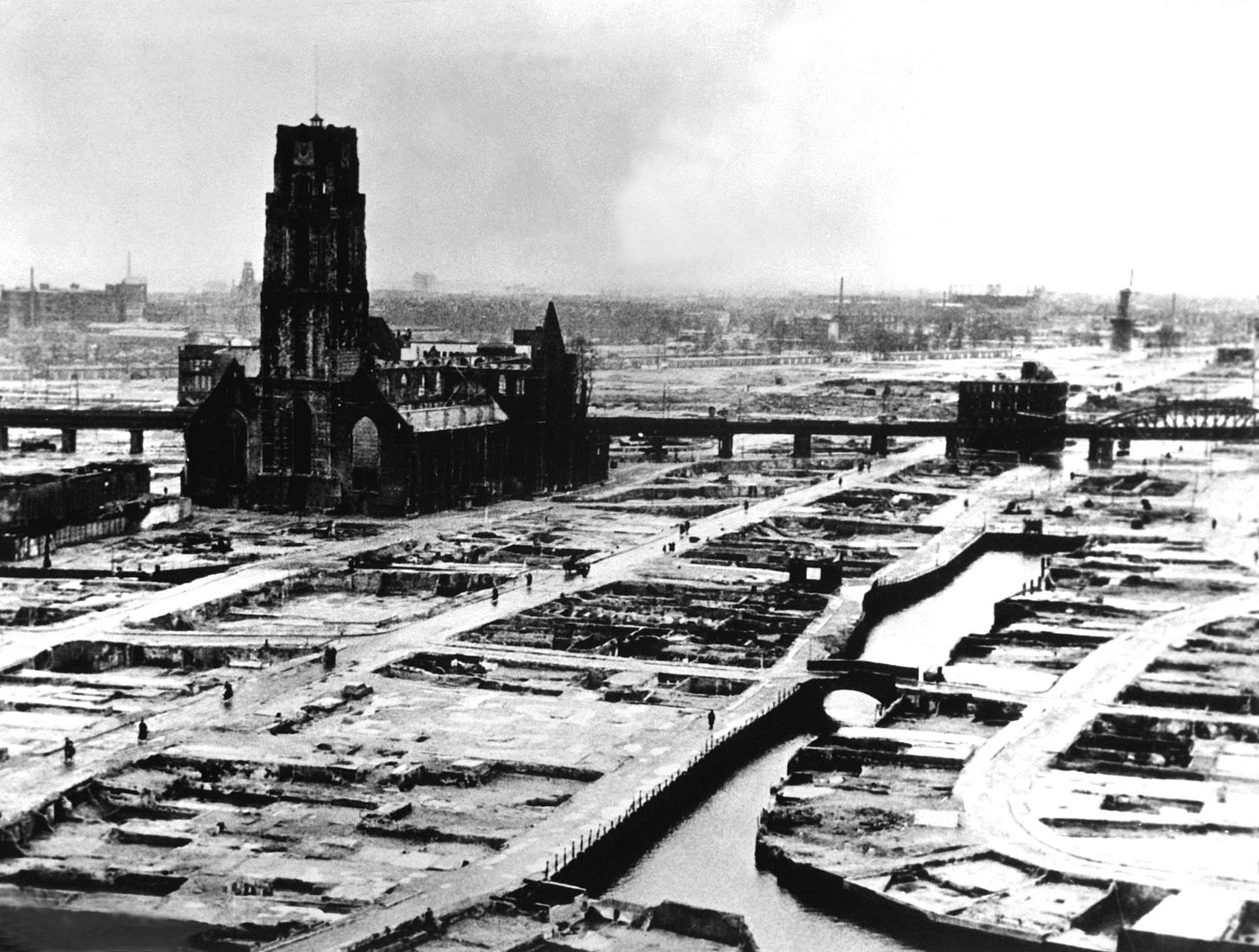

The Netherlands was hit hard during World War 2. In May 1940 Nazi forces began occupying the country. Rotterdam would be carpet bombed which resulted in 30,000 homes being destroyed, alongside almost the entirety of the city centre. There was an estimated 300,000 civilian deaths during the war, in addition to the 17,000 military deaths. Even once the war was over it would shape the country for decades to come.

Recovery was tough but by the 1970’s, even with an oil and gas crisis that greatly impacted the country, things had largely returned to normal. From 1962 up until 2004 the Port of Rotterdam was the busiest in the world, and still remains in the top 10 today. Liberal drug laws and tolerance towards gay people started to make it a tourist destination. An always interesting and sometimes experimental Dutch architecture scene was exploding. Of course its now infamous bike culture began to emerge in that decade after sometimes violent protests over the rise in child deaths by cars sparked a new social movement. And plans to turn Schipol Airport into one of the most important in Europe (which would eventually happen in the 1990’s) were well underway.

By the time the Berlin Wall fell in October 1989 The Netherlands was already a growing and strong country within Europe. However the end of the Cold War started a new era for the European Union. Eastern countries would slowly start to be considered for admission, a new pan-European currency would be developed, and it would become an increasingly interconnected super-economy that would become one of the largest in the world. Countries such as Germany, France and the Netherlands were particularly well suited to take advantage of the radical geo-political and economic shift that would take place during the 1990’s.

A vision starts to emerge

The first discussions about high speed rail in The Netherlands began in the early 1970’s. An idea was tossed around for a line from Amsterdam to Rotterdam and onward to Belgium, often called the AmRoBel proposal. But at the time the only high speed line in operation was the Japanese Shinkansen with the TGV still being in a prototype phase and roughly a decade out from launching. Being a relatively small country the perceived need for high speed service was not as great as it was in other European nations. The AmRoBel proposal ultimately went no where. But the fortunes of high speed rail would change as the end of the 1980’s approached.

The first development was the creation of a political agreement that allowed the multi-national Thalys service to be created. This is a high speed rail service, based on the the French TGV trains, which serves Paris, Brussels, Amsterdam, and Cologne, as well as major cities along the way such as Antwerp, Rotterdam, and Schipol. First formalized in 1987 it would eventually launch in June 1996, though the amount of high speed track available was limited at the time.

When Thalys was launched some of the existing “classic” services, such as the Amsterdam to Paris Etolie-du-Nord train would be cancelled. The Etoile was not exactly slow; it took about 4 hours 20 minutes to do the trip, versus the roughly 3 hours 20 minutes that Thalys takes in 2023. And it was cheaper, the equivalent of 66 Euros in todays money versus 80 to 150 Euros (for an economy seat) that Thalys tickets usually range in (sometimes there are sales but those cheaper seats rarely last long, and are almost never available last minute). The cancellation of more affordable services when high speed rail arrives is one of the aspects of the projects that is rarely ever discussed and, rather frustratingly, pretty poorly documented.

The creation of Thalys is part of what kick started Nederland Spoorwegen (NS), the Dutch railway agency responsible for the majority of passenger trains in The Netherlands, to develop a comprehensive high speed rail plan. The plan that emerged in 1988 was called Rail 21 and it centred around three projects. HSL-Zuid (South) would run from Amsterdam to Schipol, Rotterdam, and onward to the Belgian border with a small branch line to Breda. HSL-Oost (East), went from Amsterdam to the German border, and would be cancelled in 2001 (though a small part of it would semi-reappear in the Amsterdam to Utrecht modernization project). And HSL-Noord (North) which was cancelled in 2007 though it has partially reappeared as the Hanzelijn between Zwolle and Lelystad.

From the very start HSL Zuid was the top priority. Not only would it link Amsterdam and Rotterdam, the two largest cities in The Netherlands, and Schipol Airport which had become one of the top 5 busiest stations in the country, it would connect with Antwerp, Brussels (home of the EU Parliament), Paris, as well as with the high speed line that provided Eurostar service to London via the Channel Tunnel. It was an EU worthy project that represented the exuberant energy and direction of Western Europe in the 1990’s.

What about The Hague (or the trouble starts before shovels are even in the ground)

Even before HSL Zuid was under construction it faced controversies. When the first proposal was put in front of the Dutch parliament in 1991 it was brutally panned by politicians and the media. Its cost seemed too low, at €1.45 billion, with €2.25 billion being seen as a more realistic number. There was no agreement in place with the Belgians on the route (which was critical because roughly 35km of high speed line connecting to Antwerp was on Belgian territory). There was also the choice of an entirely new alignment versus other alternatives which would take almost a decade of debate to settle.

In order to achieve the fastest running time between Amsterdam and Rotterdam, and to reduce costs on that particular section, it was decided to skip Den Haag (The Hague) and go with an entirely new route. Not only is Den Haag the political centre of the Netherlands, it also host a number of international organizations including the high profile International Court of Justice. One solution was to have some high speed services start at Den Haag instead of Amsterdam. But that was ruled out meaning The Netherlands third largest city would not only be excluded from being on the high speed line, it wouldn’t even have a direct connection to Brussels or Paris. Once the high speed line opened residents of the city would ‘simply’ have to make a connection in Rotterdam in order to get to Antwerp or Brussels.

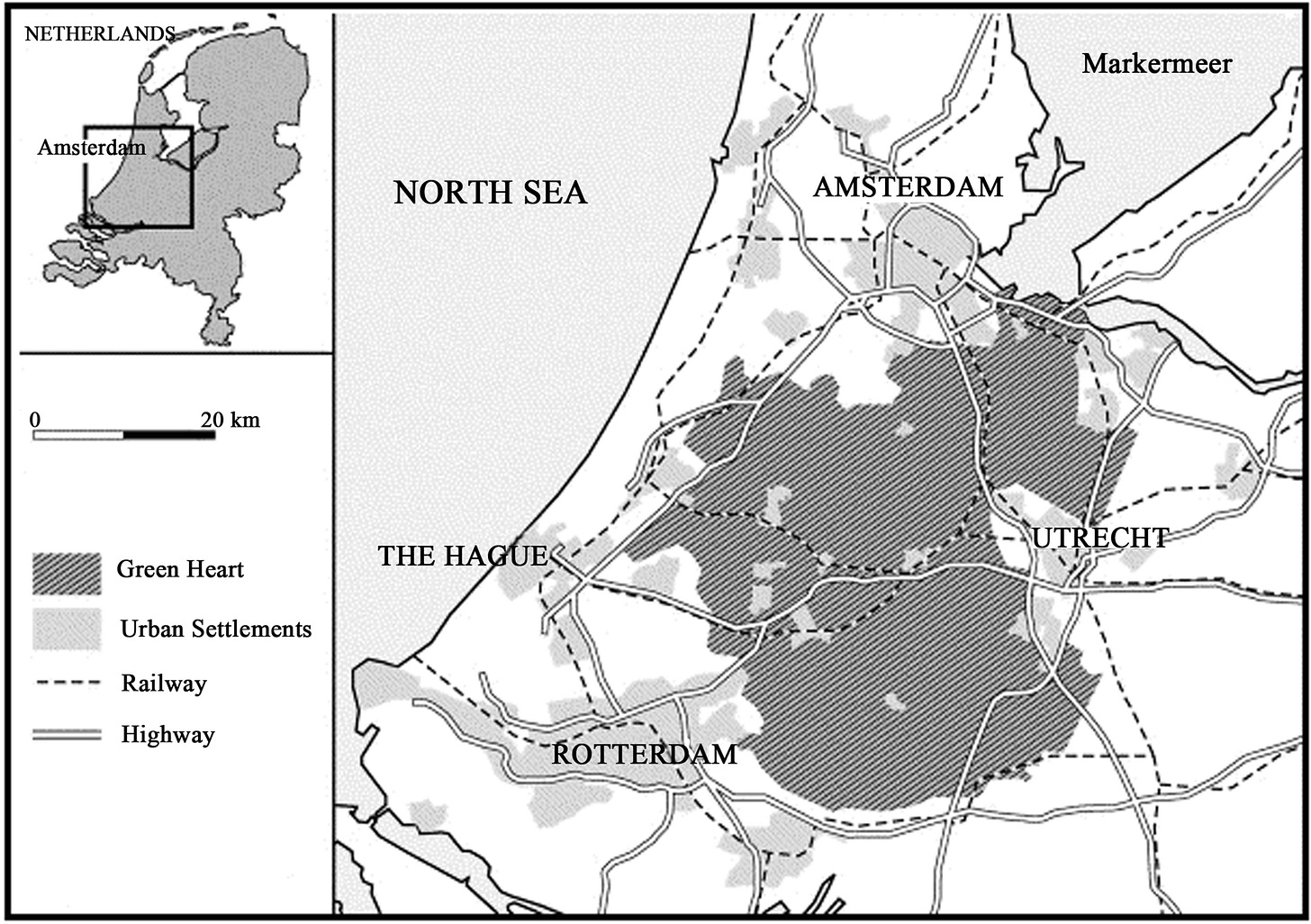

There was also a growing objection to running a high speed line through de Groene Hart (The Green Heart). For those not familiar, de Groene Hart is essentially a Greenbelt (an area of farm land and natural land protected from development that encircles part of, or the entirety, of a city) which regions like Toronto and Ottawa have. Except in this case it is the cities that form a circle around a central green space. To appease the public a 7km long tunnel was to be built under de Groene Hart, a decision which would add an additional Euro1.1 billion to the project, and raising the overall cost of the project to Euro3.5 billion by 1995.

And finally there were decisions surrounding the public-private nature of the project, and who would ultimately operate the new, non-Thalys high speed service. This is a fairly complicated part of the story and could be an article on its own (and in fact there are at least a dozen academic papers and books written about just this aspect of the project). The full blowback of these particular choices would take several decades to fully decades to transpires though objections to it were being raised from the start.

Eventually a route would be finalized and after a convoluted tendering process, construction would proceed.

The complexities of designing and constructing HSL-Zuid

One of the biggest challenges to building anything in The Netherlands is the land. While it might be flat, the country is ruled by the polder, which in simplest terms is land reclaimed from the sea, which is highly susceptible to sinking and subsiding. 20% of Dutch land fits that category and even more has to be protected by complex dykes and hydrological works due to being at or just below sea level. Amsterdam Central station famously had to be built on 8687 wooden piles in order to actually construct it in that location.

The country is also highly urbanized so while there weren't any valleys or mountains to contend with, tunnels and viaducts would still be needed to get through some of the urban areas with demolishing homes and businesses. And without getting too far into the weeds the line used a different construction method (called ballastless tracks or slab tracks) where instead of steel rails and ties on a gravel bed, they were secured directly to a concrete foundation. This meant that construction costs were higher, though in the long run ballastless tracks are supposed to have a cheaper maintenance cost. Noise emissions are an issue with this type of construction as they are higher than traditional ballasted construction, which meant that adequate noise barriers were a critical part of the project with additional ones still being installed to this day.

One of the more interesting and ultimately controversial aspects of the construction is that the basic superstructure of the line, that being the tunnels, viaducts, right of way clearing, and track foundations were funded by the Dutch government, while a design-build-maintain contract for tracks, catenary, and other supporting structural elements were issued as 30 year public-private partnership contract. This largely occurred because there was not enough private interest in building the entirety of the high speed line infrastructure. If you are wondering how companies make money off of building infrastructure, Infraspeed, the company responsible for track, catenary etc, would receive Euro100 million per year from the Dutch government for use of the infrastructure. So instead of the NS or the government building, owning and maintaining those structures, a private company builds them and then leases them back.

As Lasse Gerrits and Peter Marks discuss in their somewhat difficult and dry, but very insightful book Understanding Collective Decision Making: A Fitness Landscape Model Approach the tendering process, and the government preference to have NS involved in the project versus foreign companies, helped to create this situation. In other words as a projects stack on more requirements (be they social, environmental, or financial) the number of companies who can meet them dwindles. Complicating matters were new rules coming into affect as a result of the EU looking to open up rail operations and construction to companies outside of traditional national operators which required the tendering process to be restarted on several occasions.

Ultimately the right to operate the high speed services within The Netherlands and to Antwerp and Brussels were awarded to the High Speed Alliance, a consortium 90% owned by NS, and 10% owned by the Dutch airline giant KLM in 2001. This came at a hefty price tag of €148 million per year, though it was still lower than their original €178million per year which was done to ensure that no foreign companies could come close to that offer, thus shutting down any potential competition. This high price tag for running rights would prove highly problematic once delays started piling up towards the end of the 00’s. It was already a messy project and while the favouritism towards NS, and the hard to meet requirements of the tenders, did eliminate most private companies from potentially participating it was far from the only issue at play.

Bouwfraude… a construction industry cartel plot to fix prices

In 2002 a scandal hit The Netherlands in which a whistleblower revealed that a cartel of construction industry companies had colluded to fix the prices they were offering when bidding for jobs. It resulted in a parliamentary investigation which determined that the collusion was real, and that the HSL-Zuid project had been affected.

It was never revealed exactly how the project was affected, who was involved, and who may have been fined as a result (the largest single fine was €19 million). However it did leave people questioning how much additional cost was incurred as a result of a bidding process that involved cartel actors, versus one that didn’t. Gerrits and Marks in addition to their book published a paper in which the cost of that component of the project was €250 million higher than estimated, indicating that difference may have been the direct result of cartel collusion (though without the full disclosure of data from the Dutch government, that conclusion cannot be fully verified).

This is not the only case of government contracts and the tendering process leading to additional costs for the project. By 2007, the contracted opening date of the line, the Dutch government would have to pay Infraspeed, the company responsible for maintaining HSL-Zuid once it was fully operational, €120 million per year, even though no trains would actually be using the line. And in a few years time the government would have to help save High Speed Alliance (HSA), the consortium responsible for operating future domestic and international high speed services to Antwerp and Belgium, from bankruptcy not just once, but twice before no more help could be offered.

Problems did start to emerge during the construction of the line. A wall in an uncovered tunnel section in the Rotterdam area had to be “doubled” due to weak spots being developed, as well as an 800m section of track near Rijpwetering that had to be replaced with adjustable slabs due to the track settling more than anticipated. Nothing dramatic but it did point to the relatively complicated nature of the lines construction. The tunnel under de Groene Hart was consider one of the projects biggest successes. Despite the difficulty of building through incredibly challenging soil conditions, the tunnel was actually completed ahead of schedule and within the strict environmental requirements set out for it.

Despite some of these challenges the southern part of the line was ready for basic testing in the summer of 2005 with the majority of the construction work (not including other aspects like signalling systems) being completed in 2006. However there were other problems brewing.

Deregulation and cheap airlines

Throughout the 90’s, as Europe attempted to created a more integrated, free market economy among EU member states, airlines became one of the industries that would see these radical changes take hold. While it is beyond the scope of this article, by the early 2000’s ultra-cheap European airlines such as Ryanair and Easyjet could go from corporate boardroom idea to reality very easily, and quickly, due to deregulation. And they were starting to have an impact not just on how people flew, but travel in general.

In 2004 consulting firm McKinsey put together a report which found that because of the proliferation of cheap airlines, and other factors relating to delayed rail upgrades in Belgium, passenger volume on the new high speed services would be 17% - 32% lower than was estimated in 2001. The idea that HSL-Zuid and the accompanying lines in Belgium, France and the UK could be an airline killer was already being questioned in the mid-00’s. But construction was several years in at that point, and there was no chance for the project to adjust to these changing realities.

A new service for a new line

While the new HSL Zuid line would be well used by international service, primarily Thalys along with plans for Eurostar and German ICE trains to operate services, it was going to be the domestic and Belgian high speed services that would be the crown jewel (from the Dutch perspective).

At the heart of the service would be a fleet of entirely new, high speed trains that could reach speeds of 250km/h and would very much symbolize the new vision for passenger rail in The Netherlands. The contract ended up being awarded to the Italian company AnsaldoBreda, who had never made a high speed train of their own up until that point (not a fact that would guarantee disaster, but a risky move nonetheless). There were in fact 4 companies in total who were bidding on the project. But because of the small initial order size, just 12 sets of trains, Alstom, Bombardier, and Siemens didn’t want to invest in research and development for an all new train (they offered up much more modest solutions), while AnsaldoBreda seemed to think they could make it work.

When the final design of the train, called the V250, was released, and especially once the first one was delivered, there was an immediate love or hate it opinion of them. When viewed straight on its resemblance to a Fiat Multipla people carrier was uncanny, a car not known for being good looking. Many people found it to be ugly and awkward, even though it looked somewhat similar to Dutch trains of the past. But from most angles, and in terms of the interior, the V250 was a very good looking train. It was colourful, modern, and had a certain whimsy to it. The design was done by Pininfarina, the famed Italian car design company who had developed car designs for Ferrari, Alfa Romeo, and Lancia to name a few.

When it came to marketing the new domestic and Belgian passenger rail services the same design aesthetic used for the V250 was extended into the broader advertising and branding campaigns. The launch of this new service meant the creation of a new division of NS, called NS Hispeed, and the creation of a new brand called Fyra which most sources say was going to be for the international trains running between The Netherlands and Belgium. It was also used on domestic only trains running from Amsterdam to Rotterdam so it is not entirely clear if Fyra would have been for all of the non-Thalys high speed trains, or if there were plans for a separate domestic only brand which simply never had a chance to evolve. The name Fyra is actually derived from from Swedish and means ‘four”, representing the 4 principle cities of Amsterdam, Rotterdam, Antwerp and Brussels that the service connects. Its branding was colourful, but subdued and seemed to be attempting to create a slightly serious image for itself.

This was in contrast with NS Hispeed. The new division was responsible for coordinating online, kiosk, or in person ticket sales of all high speed trains in and out of The Netherlands, as well as advertising, and the first class lounges found in some stations. The plan may have been to have domestic only high speed trains use the NS Hispeed moniker on them, which some advertising seems to indicate with distinct liveries being created. Below are some examples of the branding and marketing campaigns that were being developed, including commercials, of the various elements of the Fyra and NS Hispeed branding. In some regards it looks like a slightly more refined “mobile phone store” aesthetic. But it was a big departure from the very conservative brand identities passenger rail companies usually employed. It wouldn’t be until nearly a decade later when Florida’s Brightline service launched that a company would embrace a similar, much more trendy identity.

It is easy to see the ambition and optimism for this service in the marketing. And it was backed up by genuine improvements in travel time. Amsterdam to Rotterdam would take just 36 minutes, and times to Antwerp and Brussels would be cut by just over an hour. At least that was the plan...

Increasing costs and escalating delays

The HSL Zuid project was never going to be cheap. But by 2007 the cost of the project was approaching €5 billion, and by September 2008 Dutch media was reporting the cost at €7.154 billion. And perhaps if the project had simply been built, even at greater costs, and worked as planned, the public might have just turned a blind eye to the problems encountered during its construction and launch.

But once the substructure and structural work for the line had been completed, about 6 months behind schedule, more problems were about to come flooding in during the testing phase. Though the line officially opened in 2006, it took 3 years to work out issues with European Train Control System (ETCS) that does exactly as it says, manages and controls train movements on the line. The problems arouse because the line was going to use the advanced, and all new, European Rail Traffic Management System (ERTMS), which was designed to be a pan-European solution to allow for improved interoperability between each countries rail networks. However this was a very new venture that didn’t begin until the 1990’s, and the Level 1 ERTMS system hadn’t even been finalized and certified until April 2000. HSL-Zuid was one of the first major projects to use it and unsurprisingly the implementation went rather poorly.

After three years the first portion of the line was finally ready for regular passenger rail service. However when the first trains started running on the line in September 2009, it was not the glamorous NS Hispeed service that had been showcased. Instead it was a once an hour train between Amsterdam and Rotterdam that used locomotives and existing NS passenger cars that had hastily been repainted in a Fyra paint scheme. It was a far cry from the initial vision that had been offered up.

High speed service would finally start in December 2009… sort of. It would be limited to Thalys trains, which would switch their service from existing conventional lines to HSL-Zuid. However, because of the ongoing issues with the ECTS system they could not run at their top speed of 300km/h and were limited to a much slower 160km/h. It wouldn’t be until May 2011 that the southern part of HSL Zuid would allow for 300km/h travel, and until September 2011 for the remaining section of the line.

By the start of 2011, before the full extent of Fyra service had been launched, the HSA was once again in jeopardy of going bankrupt due to a lack of revenue. The one service that had been operating between Amsterdam and Rotterdam, was proving to be a failure with many trains nearly empty. The situation was dire. HSA was reportedly losing €385,000 per day and the cost of the consortium going bankrupt would cost the Dutch government €2.4 billion. In part by cutting the concession fee (the payment made each year for the right to run trains on the line), a plan was put together to keep HSA from collapsing, but it would cost the Dutch government €390million. Because HSA’s life would be cut short it is unlikely the Dutch government had to cover that full amount, though it would have to fund an alternate service.

The €6 premium to use Fyra between Amsterdam and Rotterdam was cut to €2.10 in the hopes of increasing the number of people using the service (the 25% premium on ticket prices for trips into Belgium via Thalys would remain). All of this poor performance was in spite of service to Belgium, the Benelux trains, being axed prior to the launch of Fyra. The Benelux trains ran hourly, stopped at more cities (including Den Haag), and had a fixed ticket price based on distance. Yes they were slower since they were over classic lines and had more stops. But they were more flexible, didn’t require reservations, and were cheaper than Fyra which had ticket prices that were 25% to 60% higher in some cases.

The Fyra service from Amsterdam to Brussels wouldn’t actually start until 8 December 2012 and would run until 17 January 2013, a period of 40 days. The high speed domestic service using the new AnsaldoBreda trains would never run at all.

So what happened…?

Fyra goes up in flames

The fact that the first delivery was originally planned for 2007 and didn’t happen until 2009 was among the least of the trains problems (and not entirely the fault of AnsaldoBreda as ordering was somewhat delayed due to ongoing track access negotiations). Some delays were also due to the issues surrounding ECTS on the line, as well as the train needing certain certifications for Level 2 ERTMS. In most cases extensive testing would have foreseen many of the problems to be encountered but because of all the delays the testing regime for the V250 doesn’t seem to have been particularly robust.

Like an Alfa Romeo, the excellent Italian design behind the AnsaldoBreda V250 was matched up with poor manufacturing. When the train finally went into service in December 2013 it immediately ran in to problems. In one instance a floor plate had fallen off the train and onto the tracks, which caused Belgium to pull its certification of the train once it learned of the incident. Snow and winter weather made the V250 completely unreliable. After just 40 days the trains were pulled from service and were so riddled with faults that they would never see service in The Netherlands or Belgium again.

The public backlash to the problematic trains was everywhere. It was covered in the media. There were snarky memes online. It was the subject of parliamentary debate in both countries. And in one case a train that was parked in a rail yard in Amsterdam was tagged with the phrase “They’re food may be good but… Dont buy trains from Italy”.

Almost immediately after the V250 was pulled from service a legal battle between AnsaldoBreda and the Dutch and Belgian railway agencies began. Ultimately they would return all of the trains, cancel future orders, and take a €88 million hit in the process. For AnsaldoBreda this affair would be one of the final factors leading to the company’s merger with Hitachi Rail in 2015 in the face of multi-million euro losses and potential bankruptcy. The V250 was not the sole reason the company struggled, there were many other scandals and failures during the 00’s and early 10’s that contributed to it, but it was one of the final blows.

The Fyra brand became so tainted that by June 2013, just 6 months after its launch, references to it were disappearing from advertising campaigns. In 2014 the service was officially renamed Intercity Direct, and NS Hispeed as a brand was discontinued, becoming NS International. Some of the existing NS passenger cars and locomotives that had been repainted with a Fyra livery were quickly painted back with the classic NS blue and yellow paint scheme.

The debacle had caused such a public backlash that in May 2015 both the Dutch and Belgian parliaments held hearings on the affair. The Dutch report was damning and led to Junior Infrastructure Minister Wilma Mansveld resigning as a result of it. The report didn’t mince words and even the title ‘Reizigers in de kou’ which translates to ‘Train travellers out in the cold’ made the tone crystal clear.

The report found that Fyra was ‘a job half done which has cost every household in the Netherlands €1,500′. As the report goes on it starts to lay out the very complex and serious problems behind the project. It was a direct attack on the privatization of NS.

“Twenty years ago railway company NS became a privileged player on an ostensibly free market which in fact allowed little competition. The state subsidises, receives dividends (in an ideal scenario) and is still the only stakeholder in a company which bought the ill-fated trains in Italy using an Irish tax construction to avoid paying tax to that very stakeholder,”

Much of the blame in the aftermath of the report would be placed on several decades worth of politicians turning passenger rail into a “free market experiment”, a sentiment echoed by both the report and even centrist papers such as Volksrant. One part of the report lays out the overall conclusion pretty clearly.

“The intended service has not been established because other interests prevailed over providing the service. The State was too focused on monetary gains and NS was too focused on retaining its strategic position. Not only did that hinder passengers’ interest, it also meant an underutilization of the HSL-Zuid.”

It had been the culmination of two decades worth of reforms that had altered the structure and functioning of the Dutch railways. In the mid-90’s NS had been turned into an independent organization, though it would still be heavily influenced by the government when it came to timetables, fares, and service quality. At that time the responsibility for infrastructure construction and maintenance was handed off to a division called ProRail which was officially separated from NS in 2003. The increasingly ‘corporate’ mentality of NS is in part what lead it to create a subsidiary called NS Financial Services Company in Ireland to avoid Dutch taxes which allowed NS to gain an additional Euro270 million in profit, but resulted in The Netherlands losing Euro21 million in tax revenue in 2012 alone.

Everywhere you look there was blame being laid. Corporate greed and cartels were an easy target, as were politicians, the free market, a liberalized EU, a train company in over its head, and a corporatist NS, just to name a few of the actors and agents involved in HSL-Zuid’s failure. But ultimately there is no single source of the failure. Everyone played a role, going all the way back to the 1990’s when a feverish desire for a new EU and fast trains clouded many peoples minds on what actually made sense in The Netherlands.

By 2017 the High Speed Alliance venture with NS and KLM had officially gone bankrupt and was liquidated. It was a symbolic end to the original high speed rail project, even though it had for all intensive purposes died several years earlier. But efforts to develop something new in the wake of the debacle still carried on, and have still not come to reality today.

Still trying to get it right. And still struggling

While interim solutions were developed to at least bring moderate, 160km/h speed domestic and Belgian service to HSL-Zuid a more long term plan was needed. In July 2014 the process began to acquire all new trains for the HSL-Zuid services. By 2016 Alstom had been selected as the manufacturer of 80 train sets. These trains have been designed for speeds up 200km/h and like there predecessor have arrived late, and are struggling with quality issues (including welding issues which is a serious, not easy to fix, problem).

As it stands these trains will not enter service until Summer 2023 and even then there is no guarantee being given by NS that the date will not be pushed back even further.

Even when the new trains are finally in service they will not meet the original vision of the NS Hispeed program. Amsterdam to Rotterdam, which currently takes 43 minutes, will likely take 40 minutes, which is still short of the original travel time of 36 minutes. Likewise with service to Breda, and non-Thalys service into Antwerp and Brussels.

On the international side things faired slightly better, but not by much. Thalys is perhaps the only bright spot, with 28 trains per day using the line (14 in each direction). However this number is somewhat inflated as Thalys service was increased due to the failure of Fyra. Had that program been successful there would have been at least a half dozen fewer Thalys trains today.

Eurostar would not launch until 2018, and as of today there are only 2 round trips per day between Amsterdam and London. The travel time of this journey is 3 hour 52 minutes, but passengers need to be at the Eurostar terminal at least 30 minutes before departure (if you are late, you cannot board), which in reality means being at the station 45 minutes to an hour before departure, versus being able to simply show up and board minutes before any other train journey. This has made it a tough sell versus flying which even with all the transiting and check in requirements is still quicker, and often much cheaper. The plans for German ICE trains to run from a few cities across HSL-Zuid, through Belgium, and onward to London never happened.

As it stands today there are only 2 trains each hour (one in each direction) that actually use HSL-Zuid at high speeds, leaving the high speed nature of the line highly under-utilized. In 2018 interim Benelux services that were restarted due to the failure of Fyra that offered direct connections for people in Leiden, Den Haag, and Dordrecht were discontinued. Four trains daily between Den Haag and Brussels remained, mostly due to political pressure to at least keep some direct service between the two capitals. But those final holdouts would eventually be cut a few years later.

The other “sort of high speed”, less disastrous Dutch rail projects

While HSL-Zuid has been the focus of this article so far, it wasn’t the only “high speed” rail project in The Netherlands during the 00’s and early 10’s. Nor is it the only line that has failed to live up to its promise.

Two lines have been built for 200km/h service, the all new Hanzelijn from Zwolle to Lelystad, completed in 2012, and the upgraded line from Utrecht to Amsterdam, completed in 2007. They employed design features such as full grade separation, geometry suitable for higher speeds, and an electrical system that could be easily converted to the higher voltages used by fast trains. Unlike HSL-Zuid they used conventional methods for track construction.

However, as of today service on both of the lines is capped at 140km/h. Part of the reason the speeds are not higher is the only fast trains that actually use the line are German ICE trains, which are even less numerous in terms of service than Thalys is on HSL-Zuid. Without high speed domestic trains, it makes very little sense to alter the operation of the line at the time being. That should change as enough new equipment is delivered and certified, but that is at best 5 - 7 years given the delays seen already.

These two lines have been less scandalous since they still offer some pretty important benefits in their current state. The line between Utrecht and Amsterdam is one of the most important sections of the rail network and the additional capacity, and improvements to safety and reliability was very much needed. The line between Zwolle and Lelystad was a completely new alignment and has helped in providing better and faster links to the north. In the case of going from Dronten to Zwolle the travel time by public transport dropped from 66 to 18 minutes and Dronten to Lelystad was reduced from 30 minutes to 12.

At least one of the lines was also cheaper. The Hanzelijn was €1.1 billion for 50km of track, 2 new stations, and station upgrades in Lelystad. Even on a per km basis the cost of the Hanzelijn was about 2/5 of HSL Zuid, making the current short comings of the project less susceptible to public backlash. Definitive cost estimates for the Amsterdam to Utrecht project could not be found, but its per km cost is almost certainly cheaper than that of HSL-Zuid.

There is one major new line project in the works, which is currently estimated at anywhere from €3 - 8 billion, depending on the source, and that is the roughly 130 km long Lelylijn. This is a new line from Lelystad to the northern hub of Groningen, and is a spiritual successor to the HSL Noord plan from the late 90’s. It will not be built to 300km/h standards, as had been envisioned at various points in the past, but will instead follow the same model as the lines between Zwolle and Lelystad and Utrecht to Amsterdam and be constructed to a 200km/h standard. Throughout the various articles written about the line there doesn’t seem to be a huge sense of urgency or prioritization of this project, at least not to the same degree there was for HSL-Zuid. But part of that interpretation could come from the automated translation from Dutch to English used in order to read the majority of Dutch language articles.

If not high speed rail, what are the Dutch focusing on when it comes to passenger rail?

Before the concrete was even dry on HSL-Zuid it was clear that a different approach towards passenger rail investments was going to take shape in The Netherlands. Over the past two decades the focus and priorities has remained relatively consistent.

By all accounts the Dutch have essentially shelved future high speed rail ambitions for the coming decade or two. In fact the focus seems to be shifting the other way with more of a focus on frequent services that serve many stops, supported by the development of a new lightweight NS City Sprinter train.

In 2019 the Dutch government released Public Transport in 2040, a plan for investment and expansion over the next two decades. Not much has changed from the priorities expressed, or seen in action, since the mid-00’s. There are very few references to high speed rail. HSL-Zuid is mentioned since there is a desire to use a portion of it for better service from Den Haag and Rotterdam to Eindhoven. And there is mention of an improved line from Utrecht to the German border and leading into Duisburg. But that is it. Everything is business as usual with a focus on improving efficiency of the current lines whether it be through keeping things in a state of good repair, targeted optimizations, or in a few cases major works like quad tracking or rebuilding stations and urban sections.

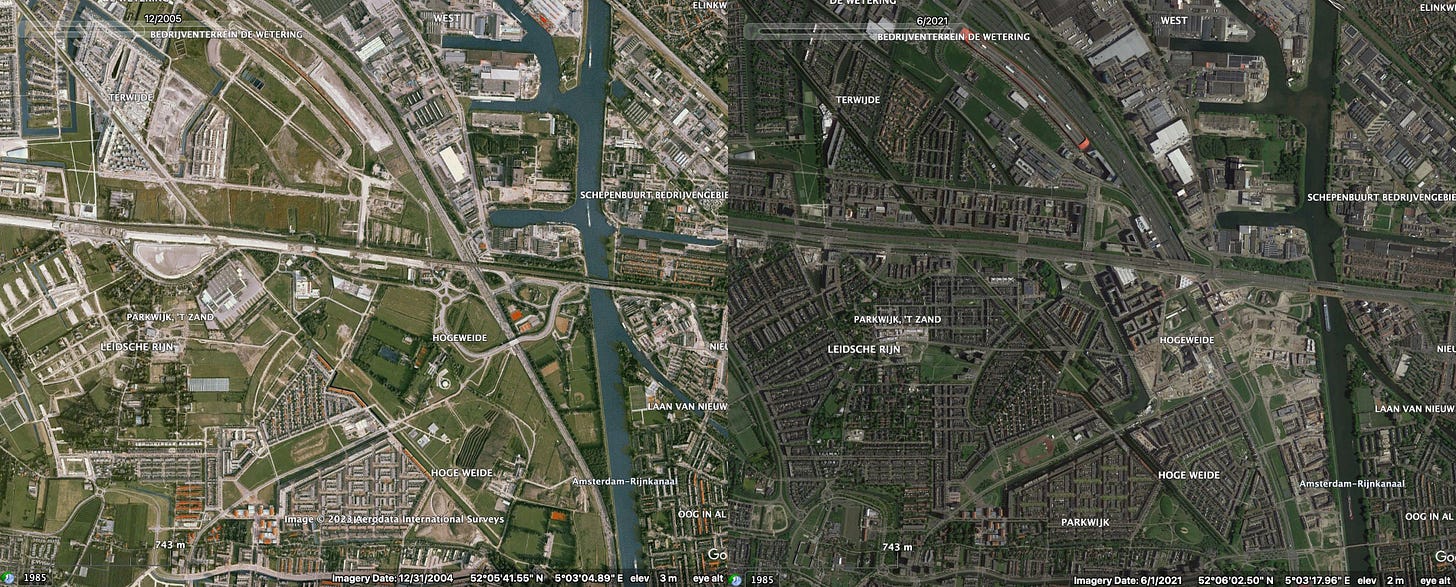

Projects over the previous two decades offer a lot of insight into what the future will hold. In the early 00’s Utrecht was a hot bed of activity. Not only was the line to Amsterdam being upgraded, but so too was its central station, as well as work done to other lines leading into the city. On the line that serves Gouda, Den Haag and Rotterdam, a new station, Utrecht Leidsche Rijn was added, which would also serves as the transportation hub for the redevelopment of the area surrounding it. Additional suburban stations were added to line heading to Eindhoven and the one heading to Amsterdam. The Netherlands has always had a long tradition of very detailed, long term spatial planning, coupled with transportation network design, and the work in Utrecht was a clear sign that this long standing paradigm of Dutch planning was going to continue in full force.

Groningen is another city that would see this same strategy applied to it. From the early 00’s onward there was increased redevelopment around its central station. And now, with the upgrading and modernization of that station, not only will passenger service be able to be improved, but the removal of the rail yard next to the station is going to allow for high density development to create a much more appealing, complete central district.

The idea that all European train stations are nestled in the heart of an urban neighbourhood, or the centre of a twee, small town, is in fact not at all true. Many of the rail stations in The Netherlands have large rail yards next to them, creating a dead zone in the centre of the towns or cities. In recent years there has been an effort, like the case of Groningen, to move the yards to the edge of the city, in conjunction with station improvements and track upgrades, to reclaim the land for better uses.

Perhaps one of the more interesting projects is the upgrading of Amsterdam Zuidas station. Zuidas is a district which was planned to become the new financial and corporate core of Amsterdam since there was very little room for new office buildings in the city centre. It’s growth has been slow but it has slowly established itself as a critical district in the city and in 2030 all international trains will stop using Amsterdam Central and instead use Zuidas (which had a moderately costly metro line connection built from Zuidas station to the city centre in recent years). The station will not only see new platforms, but also the highway next to it buried, and a series of other changes that will facilitate the planned increased in passengers using the station.

Whether this move will prove beneficial for international services remains to be seen. There are arguments that could be made as to why this isn’t a great idea. But it is indicative of the current way of thinking within the NS.

The examples above are just a selection of dozen of projects like this that have taken place across The Netherlands over the past 20 years. Domestic needs have been put front and centre, and while the corporatist ideology of NS is still strong as its new stations are also designed to be retail hubs bringing in high rents, there is also a desire to use the infrastructure investments to better the neighbourhoods the stations are in.

What are the implication and lessons to be learned for North America

It would be very easy to say the Dutch high speed rail project was a lesson in hubris, greed, corporatism, politicking and bureaucracy run amok. And yes, all of those factors were at play.

But a lot of the failings were the result of human nature. After a brutal war that devastated Europe and took the Western countries decades to recover from (Eastern countries even longer since they could not fully rebuild until after the collapse of the USSR) it was no surprise that Europe and the EU concept were riding high. It is completely understandable why a sense of drunken euphoria took hold as economies boomed and it finally felt like they could put the last vestiges of the horrible war behind them. Anything seemed possible at the time, and the bigger and bolder it was, the better it seemed.

By the time the early 2000’s rolled around, some of the sheen had worn off, a few warning signs were flashing, and more rational heads began to prevail. It was becoming clear that the grand high speed rail vision set out in the Rail 21 plan didn’t make a lot of sense for the small, dense country. But with HSL-Zuid well underway, there was not turning back. And once a cascading series of mistakes, missteps, scandals, and yes hubris laden decisions, began to arise, the project was well on its way to becoming the debacle that it still is today.

In just 7 years the price tag of the project doubled, from the time it started construction and a final tally would likely put the final costs closer to 2.5 times the original pre-construction estimate (and 3.5 to 4 times the original estimate). All for a piece of infrastructure that is still highly under-utilized fourteen years after it was opened for public service. Even once new trains are finally able to run and provide service to the public, the original vision will not be met, even as the last of the cheaper, lower speed services are once again terminated in order to ‘push’ people towards the higher speed, but more expensive ones.

Yet it could have been a lot worse had plans for other HSL-Zuid style lines not been abandoned at the start of the 2000’s. For all the mistakes made, the most important decision, and lesson, was the ability to pump the brakes on future plans, and at least avoid repeating the same mistakes in other parts of the country.

Instead of the ‘glamorous’ high speed lines there have been strategic investments in existing lines to improve capacity, reliability and safety, and an incredible program to modernize stations and remove unsightly rail yards from city centres to the suburban fringes to allow for more transit oriented development. It is essentially the model being used in many North American cities, in particular in Toronto and the Greater Golden Horseshoe region (minus the removal of rail yards which were mostly relocated from city centres in the 1960’s and 70’s). Some projects, such as the proposed and quite likely to proceed Lelylijn will still be expensive and allow for speeds up to 200km/h, but should come in at half the cost and scale of a faster HSL-Zuid style line.

The Dutch experience shows how easily it is to get caught up in hype and hysteria for the “super fast, gee-whiz” passenger rail projects, instead of focusing on the core regional and intercity services, along with quality of life improvements to stations and their surrounding areas. As strange as it might seem even in Europe, that magical and amazing land of high speed rail, there are critics, there is rational opposition to it, and there are even countries who do not see blazing fast TGV style service as being critical to the future of travel. And were it not for anti-consumer “supporting” measures, like cancelling classic intercity services, or banning short haul flights as France is attempting to do, the ridership of high speed rail might not be as wonderful as it looks today.

It isn’t that high speed rail is bad. It is something that makes sense when you already have existing classic lines that are completely maxed out due to demand. But just because you build it doesn’t mean people will come nor will it be a guaranteed airline killer. There are dozens if not hundreds of factors at play when it comes to whether a high speed line is a good use of public money and will actually be of benefit for more than just a small, well off fraction of a population. The Dutch learned that lesson a very hard and expensive way.

As parts of Canada and the US start to look at high speed rail more seriously there needs to be a lot more understanding of the entire high speed rail experience in Europe and other places (The Netherlands is not the only place in which high speed rail has been a scandal and disappointment). Unfortunately if North America can’t learn from those lessons then the absolute disaster that is the California high speed rail project is simply going to be replicated in the Quebec-Windsor corridor, the Northeast Corridor, maybe even between Dallas and Houston. Except that in the first two cases, the boondoggle and scandal that will result could be even greater than what is being seen in California.

If you want to find me on social media you can do so @Johnnyrenton.bsky.social on Bluesky. If you have any thoughts or feedback let me know in the comments.